The first time I was fired by Robert Evans, I figured at the very least I was in good company.

After all, he’d fired Francis Ford Coppola off of The Godfather multiple times, and yet they churned out a masterpiece. Which proved Bob’s often-stated belief that pictures where people actually get along end up a bust. He thought conflict was what created great films.

As I shuffled out of the plush Paramount suite for what I assumed would be the last time, I heard a halted whisper. “Jay, get back in there. Just say something, anything,” said Evans’s executive assistant, Michael Binns-Alfred. I went back in, hat in hand, and thanked the maestro for the opportunity to work with him. He furrowed his brow, looked at me from above his custom specs, and nodded.

Here’s a primer for the uninitiated. He was Bob Evans, the Kid Notorious. Never his birth name, Robert Shapera, and rarely his proper stage name, Robert Evans, for that would be too common. His fourth wife, Phyllis George, once left a voice mail alarming our entire staff with the news that he had passed away—but she had been mistaken; it was Bob Evans, the owner of the steak-house franchise, who had died. “Expect the unexpected … ”

Bob Odenkirk has said that the unflappable hustler Saul Goodman from Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul was modeled after Evans. Even more direct, though, was Odenkirk’s legendary Mr. Show sketch, “God’s Book on Tape,” where he played a contemplative, wistful version of Evans as the Almighty.

As far back as Robert Vaughn’s off-the-mark impersonation in the Blake Edwards flop S.O.B., people have been imitating him with varying degrees of success. More recently, Matthew Goode played Evans in Paramount’s myth-building 2022 mini-series The Offer, chronicling the making of The Godfather and the 70s tumult of “the mountain,” as the studio was known in the era. One of the more notable takes was that of his frenemy Dustin Hoffman in the film Wag the Dog, where the actor even wore an Evans-style silk shirt. Among the least noted? As the Los Angeles Times reported, the infamous and brutal dictator Kim Jong Il based his personal style on Evans’s. I guess it explains the oversize glasses and obsession with filmmaking.

I came to work for Evans while still at Chapman University, after pounding the pavement with whatever tactics I’d gleaned from What Makes Sammy Run? and Fitzgerald’s Pat Hobby stories. What a trip—driving from class straight through “them Windsor gates,” as Bob called the entrance to the Paramount lot. I happened to join the company during a transitional period, a flurry of scripts, Bankers Boxes, frazzled execs, and frenzied assistants.

My first months with the company were akin to The Wizard of Oz or Charlie’s Angels: I never saw the man himself. Occasionally the phone would ring and I would hear the voice—the dulcet tones that I knew so well from his hypnotic audiobook. When I finally did meet Evans face-to-face it was under typically urgent and dramatic circumstances. At the very last minute, he decided he wanted to hold a Christmas party at his offices on the lot—something he hadn’t done in years—and not only that, he also wanted to screen a print of Peter Jackson’s then brand-new King Kong remake, at the behest of his spunky then wife (No. 7), Lady Victoria White.

Thanks to a series of frantic phone calls to Nina Jacobson, over at Disney, we were able to get a print of the movie and, by a miracle, find a projectionist. When I called him up in the booth to ask if it was all right for our guests to bring their glasses of wine into the theater, he replied, “For Robert Evans? I don’t care if you bring an eight ball with you!”

The party included Slash, complete with leather pants and two still-sealed cigarette packs in one hand; Evans’s unassuming accountant; and a gaggle of kids. It was an odd bunch. Though, come to think of it, it always was a bit eclectic at the Evans household—a diet-pill-dealing socialite one minute, a knockout Romanian “rocket scientist” the next … the vibe somewhere between James Bond and Shampoo.

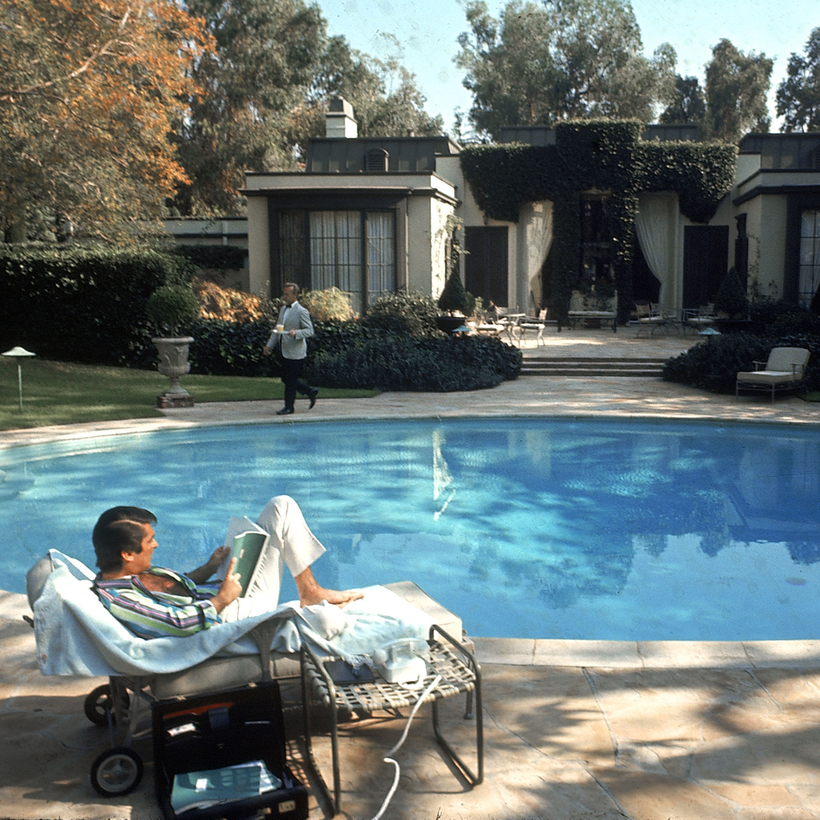

Every time someone found out I worked for Evans, I always got the same question: “Is it true he takes all of his meetings in bed?” The answer was a qualified yes—at least since the Johnson administration. In a Life-magazine spread, playfully skewering his picaresque rise in show business, Evans is seen exactly as he would be seen in myriad Instagram posts decades later: on the phone and draped in silk pajamas. Even the Griffin-shaped lamps were the same. Being on In Bed with Robert Evans, as his Sirius radio show was titled, truly was a rite of passage in the Hollywood of yesteryear.

Though Sunset Boulevard, with Norma Desmond’s opulent but decaying estate, would be an easy comparison and cheap shot, there’s another movie, one he and I discussed many times, The Bad and the Beautiful, that always resonated a bit more. Like the flamboyant and ultimately exiled producer played by Kirk Douglas, in the end Evans both allured and alienated.

“Notorious” and “Irish”

Once, Evans got a call out of the blue from the tasteful and well-liked Paramount studio head Brad Grey, telling him that he wanted to meet. Evans optimistically assumed this would mean a “go” project, but that wasn’t what Brad had in mind. No, Brad wanted Evans to come along with him to Brown University for their student-run Ivy Film Festival. Brad explained that the previous year he had coaxed Martin Scorsese into giving a master class on filmmaking. This year, he wanted to do a Paramount retrospective with Evans. But he had one more big ask. Could Bob get Jack Nicholson to join as well?

Brad had just recently produced The Departed and yet was coming to Evans, who hadn’t had a film in years, to get Nicholson down from Mulholland Drive. Of course, “Notorious” and “Irish” were thick as thieves, and so Evans, with typical panache, secured Nicholson easily. It probably didn’t hurt that Nicholson’s daughter was also a student at Brown.

Grey apologized that we had to take the G5. “Sumner took the G6,” he said. Perhaps to balance out the larger-than-life presence of Evans and Nicholson, we were joined by Peter Bart, a former Paramount executive turned journalist, who tore through books and injected the occasional barb, including one about Nicholson getting emphysema from his incessant smoking.

I woke the next morning to loud sounds from the hotel.

“Jay, JAY!!!”

I jumped out of bed and looked through the peephole, having stayed up too late enjoying the Rhode Island gift basket complete with the Mayor’s Own Marinara Sauce (who knew?), only to see Evans shuffle down the hall. As I quickly got him together, he gave me a brief rundown of Providence, placing his finger on his nose: “The boys.” Read: Cosa Nostra.

There was one problem. Paramount hadn’t arranged the makeup. Perhaps they had forgotten about Evans’s brief but splashy career as an actor, first under contract to MGM, then with Fox. In a frenzy, the studio managed to coax one of the makeup salesladies at Macy’s across the street over to the hotel room. The rush job turned out fabulous, and we had Evans at Brown University on time, the autograph seekers immediately thrusting themselves forward as he got out of the car. The first headshot put in front of him? Jack Nicholson’s.

Evans has always been an anomaly to me, a man out of time. During his reign in the 60s, he was seen as a throwback to the Hollywood of yesteryear, and yet today he is remembered as a pop-culture icon of 70s-era excess.

Few others successfully bridged both the studio system and New Hollywood. Warren Beatty was one—like Evans, a studio contract star who ended up making innovative pictures that pushed the limits of popular filmmaking. We once ran into Beatty at the Polo Lounge. We were in the middle of a tedious meeting, listening to a boastful young exec who was going on about how he grew up near Warren Beatty and had even briefly spent time with him before. Well, Beatty walked in and made a beeline for our table. He kissed Evans right on the lips and ignored everyone else. Bob was the veritable cat that caught the canary.

Another time we went to El Compadre, a divey, dilapidated Mexican joint in West Hollywood, to discuss our then upcoming pilot Urban Cowboy. We were surging with enthusiasm to get this project off the ground after pitching Paramount a hard-hitting and dramatic reboot that would be akin to Friday Night Lights. (Unfortunately we ended up with something more like ABC’s Nashville.) The moment we walked in, the Paramount execs rushed over and escorted us to the table. Instead of discussing the project, the meeting primarily consisted of them fawning over Evans, and by the time we were about to leave there was literally a line extending down the length of the table to take the pictures.

A sadder memory was when we screened Francis Coppola’s new re-edit of The Cotton Club on Thanksgiving weekend, 2017. Evans was incredibly proud of the film and truly impressed with what Francis had done, bringing it much closer to the vision Evans originally had in mind. We’d just seen it, and Evans was now eager to show it to his longtime friend Sumner Redstone, especially as this cut had yet to receive any distribution. So with that, we orchestrated a cloak-and-dagger screening at the Paramount lot on a Saturday.

In typical Evans fashion, he arrived at the studio with his butler and Victoria’s Secret bigwig Ed Razek. As the still-imposing Redstone was hoisted in by his loyal assistants, they handed him an iPad to answer “yes” or “no.” (Maybe I just missed it, but I never saw the rumored third option, “Fuck you.”) The film was stunning, even on the third viewing. The push and pull of Evans and Coppola had made magic again, and here finally was a chance to redeem it. Unfortunately the screening turned out to be autumnal. Sumner was moaning incessantly, Evans had rallied and was nearing the end, and our close friend from Paramount security, Rick Madrid, canceled his Thanksgiving golf weekend in Palm Springs just to be there, per Evans’s personal request. Madrid passed away suddenly only a week later. Bob died in 2019.

When I left the office suite for the very last time, I was sad to see it go. As I took down the picture of Evans with Paramount co-founder Adolph Zukor, I was reminded of Zukor’s advice to Evans when he took the reins of the studio, in the mid-60s: “Listen, kid, don’t make a picture longer than 20 minutes. No one wants to see that!” Maybe Zukor was onto something, with the appetite for millennials and Gen Z seemingly to be for short-form content.

In the 60s, he was seen as a throwback to the Hollywood of yesteryear, and yet today he is remembered as a pop-culture icon of 70s-era excess.

Were there a lot of Evans wannabes? You bet your ass there were. And still are, for that matter. Problem is, no one can quite capture the panache. Evans was bold without being boorish. Elegance, not arrogance, was the name of the game. His eye for talent was unparalleled. But sometimes you pay a price for being ahead of your time.

For Paramount’s 100th anniversary, in 2012, filmmakers and stars galore were invited to be part of a historic photo for Vanity Fair. For some reason, though, Evans was not invited. This echoed a similar event many years earlier when he watched from the window of his Paramount office as a commemorative picture was taken. At the last minute, however, we received a call from a Paramount flack. “Hi, we got a call from Sumner Redstone’s office and they told us that Mr. Evans will be joining us for the photo shoot. Here are the arrangements.” This time, the kid did indeed stay in the picture.

As Evans, his butler, Alan Selka, and I arrived at the shoot, we were faced with the self-satisfied charm of George Clooney. Mickey Rooney, looking like Methuselah himself, was hoisted out of a van. John Landis, now a dead ringer for Leonard Maltin, was overheard taking a cheap shot at Evans’s expense. Standing in the opulent greenroom in virtual silence, we truly felt like wallflowers at the dance. The first voice we heard was a familiar one: Harrison Ford paying his respects to the maestro. As soon as he did, nearly everyone else followed.

As I watched last year’s Oscars, while others were absorbed with discussing the social relevance of Will Smith’s slap I was glued to the screen when Francis Coppola publicly gave credit to Evans for his contributions to The Godfather. If only the Academy could do the same. That Evans never received the Thalberg—a lifetime-achievement award named for the very man he had played in Man of a Thousand Faces and who, for all intents and purposes he was the second coming of—was a major slight to say the least.

As for immortality, the influence of Evans’s Paramount run is everywhere. The pasta place down the street imitating The Godfather font and marionette hands? Check. A sitcom paraphrasing the immortal dialogue in Chinatown? Check. The influence of his films and the enormous dent they made in pop culture will be felt for generations.

As Evans was fond of saying, “You only gotta worry when they stop talking about you.” And in his case, that ain’t going to happen anytime soon.

James Sikura, a former longtime development executive for the Robert Evans Company at Paramount Pictures, is a Los Angeles–based independent film producer