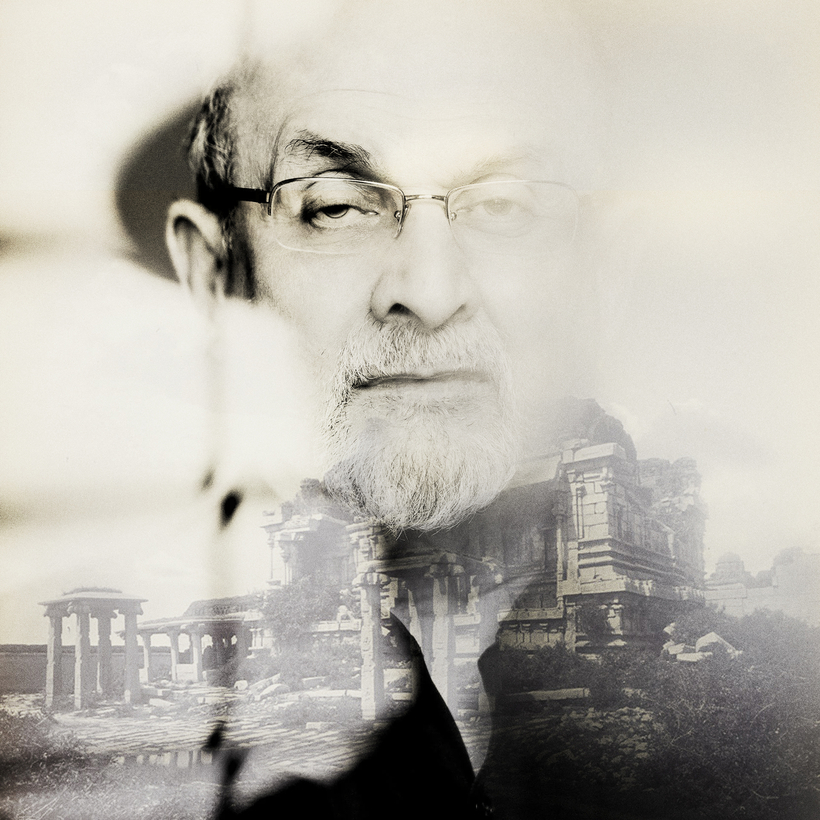

There is a slightly awkward moment towards the end of Salman Rushdie’s latest novel, the 15th in his long and successful career, when the ruler of the Indian kingdom of Bisnaga, literally “Victory City”, welcomes five sultans of the neighboring principalities to his palace and has “a number of unpleasant thoughts about followers of that religion which it is unnecessary to repeat here”.

At the time he wrote this, before the savage attack last August that left him blind in one eye and without the use of one hand, perhaps Rushdie thought it was now possible to joke about the fatwa that had been placed on his head by the Iranian government in 1989. After all, as long ago as 2007 he was quoted as saying, “It’s reached the point where it’s a piece of rhetoric rather than a real threat,” and it had been many years since he was forced to spend his time being moved by armed bodyguards from one safe house to the next.