A few years ago, Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., filled the center of a spiral staircase in its lobby with a tower made of books written about Abraham Lincoln. Eight feet wide, it stood three-and-a-half stories, 7,000 volumes in all, which is easily less than half of the books written about our 16th president.

If you were an impossibly fast reader and could consume a book about Lincoln every day, it would take you more than 41 years to read them all.

Then you could start on the newest ones. They keep coming. I just finished Jon Meacham’s fine new biography, And There Was Light, the 16th I have read, from Carl Sandburg’s elegiac six-volume hagiography, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) and The War Years (1939), to David Herbert Donald’s acclaimed Lincoln (1995), to Michael Burlingame’s monumental two-volume treatment, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008).

Over the years I have also consumed dozens of Lincoln books that are not biographies, but which focus on an aspect or incident in Lincoln’s life, such as Garry Wills’s powerful Lincoln at Gettysburg (1992), about his epoch-shifting speech, and William Lee Miller’s moving Lincoln’s Virtues (2003), which charts his evolution as a moral thinker, and many, many more.

By now I am familiar with nearly every anecdote, witticism, speech, tragedy, crisis, defeat, and triumph that scholars have been able to squeeze out of the fading record of his all-too-short 56 years. I’ll read the next big one, too.

Which raises the question—why? I know the story practically by heart, and every time it ends with a bullet to his brain. In the field of American history, Lincoln is like the Matterhorn. No matter how many have been there before, historians and biographers feel compelled to climb it. Given his central importance to the American story and the stirring drama of his life, his tale is what we reporters used to call “too good to make up.”

If you could consume a book about Lincoln every day, it would take you more than 41 years to read them all.

He steered boats up and down the Mississippi River, suffered crippling depression, endured stinging electoral defeat and then startling triumph, suffered terrible abuse from nearly every quarter while saving the Union, abolished slavery, and replanted the American experiment firmly in its founding ideals. You can’t understand this country without some acquaintance with Lincoln.

So the books keep coming. But what is it that compels readers like me to keep reading them? Clearly there are many of us; Meacham’s book, as of this writing, has spent 14 weeks on The New York Times’s best-seller list.

One reason is that each new book is different. The details may be the same, but as time passes, authors find new meaning in different things.

Meacham, for instance, unearths a story long overlooked. He describes in detail the day, February 13, 1861, when Vice President John Breckinridge, one of the candidates Lincoln had defeated in the recent election, presided over the formal certification of the election’s results.

Breckinridge was no fan of Lincoln or the Union cause. His Kentucky family enslaved people, and he fully sympathized with the rebelling states. He would go on to serve as a Confederate general and eventually as the rebellious states’ secretary of war. Breckinridge stood at center stage in the darkest moment of American history. The nation teetered.

There were rumors of serious plots to prevent the transfer of power. Lincoln himself had slipped into Washington quietly to evade assassination. Anticipating violence, 100 loyal policemen from New York City and Philadelphia arrived to line the hallways of the Capitol Building.

But the ceremony went off without a hitch. Breckinridge, mindful of his sworn duty, presided, as one contemporary congressman wrote, “with Roman fidelity … and the nation was saved.”

I know the story practically by heart, and every time it ends with a bullet to his brain.

It would, however, take a bloody civil war to save the Union, and Breckinridge’s honorable act has long been eclipsed by all that followed. It isn’t mentioned in previous Lincoln biographies, even in Burlingame’s exhaustive account. But here in 2023, as Meacham knew, we cannot miss the parallel with Vice President Mike Pence’s formally certifying the 2020 election eight score years later.

There are few such surprises in modern retellings; each new Lincoln volume tends to reveal more about its author than its subject. Lincoln was an epic hero to Sandburg, the poet. To Godfrey Rathbone Benson, the first Baron Charnwood, he was admirable but unalterably common: “Men who have risen from poverty … are generally obtuse to the minor indications by which shrewd men of education know the imposter.” His Lordship also disapproved of Lincoln’s beard.

To Donald, a pre-eminent scholar of American political history, Lincoln was a canny politician. To Doris Kearns Goodwin, the narrative biographer, he was the artful manager who turned enemies into friends and collaborators, and to Miller, the ethicist and former speechwriter for Adlai Stevenson, Lincoln was a man whose moral compass evolved throughout his life, enabling him to steer the nation through its worst ordeal.

For his part, Meacham sees spiritual evolution in Lincoln, from a notably irreligious youth toward a deepening sense of a divine presence in his life, the nation, and in human affairs. Meacham, it should come as no surprise, serves as canon historian of the Washington National Cathedral.

So each new take on Lincoln’s life is like a cover version of a great old song, inducement enough if the writer is worth reading. But the real motivation is neither a more modern take nor a fresh authorial perspective. The real reason to keep reading Lincoln biographies is simpler. You do it for the sheer pleasure of his company.

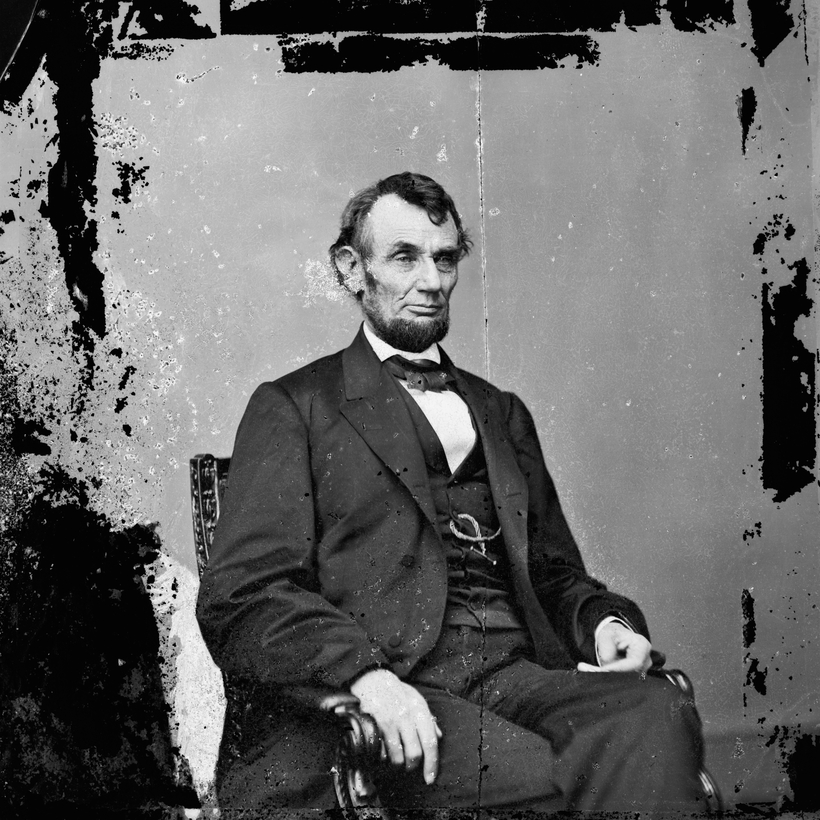

That magnificently craggy face, stiffly captured in hundreds of photographs, reportedly shed its homeliness instantly when animated by his intelligence and his wit. Daniel Day-Lewis, portraying Abe in Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film, Lincoln, captured his charm and got his high-pitched voice and hayseed accent right, and screenwriter Tony Kushner—no doubt influenced by Goodwin and Donald—portrayed the shrewd political mind that lived alongside the immortal rhetoric.

Each new take on Lincoln’s life is like a cover version of a great old song.

What’s more, Lincoln was seriously funny. Moncure D. Conway, a minister, wrote after meeting Lincoln, “The charm of his manner was that he had no manner; he was simple, direct, and humorous.” Even his anger was tinged with wit. When a delegation of Southern sympathizers from Baltimore warned him that Marylanders would resist the passage of Union troops through their state, Lincoln told them, “They can’t crawl under the earth, and they can’t fly over it,” before firmly stating that if the troops were resisted, “I will lay Baltimore in ashes.” The delegation threatened that 75,000 Marylanders would rise up, to which Lincoln promptly replied, according to Burlingame, that “he presumed there was room enough on her soil to bury 75,000 men.”

For a man of profound ambition—his law partner William Herndon called it “a little engine that knows no rest”—Lincoln could be stunningly egoless. Asked why, as president with sweeping war powers, he did nothing to counter frequent personal attacks by the Maryland abolitionist congressman Henry Winter Davis, Lincoln coolly responded, “It appears to do him good, and does me no injury. What’s the harm in letting him have his fling? If he didn’t pitch into me he would into some poor fellow whom he might hurt.”

He performed a delicate balancing act leading a war against a slave power while trying to keep border slave states in the Union—“I hope to have God on my side,” he reputedly said, “but I must have Kentucky.” He knew that his only hope of eradicating slavery was to win the war, a fact that eluded many of his abolitionist critics.

To churchmen who pleaded with him to act immediately because it was “God’s will,” Lincoln responded: “I hope it will not be irreverent for me to say, that if it is probable that God would reveal his will to others, on a point so directly concerned with my duty, it might be supposed he would reveal it directly to me.”

And while he may have been a skillful politician, he was unswerving when he believed he was right. Faced in 1864 with what many, including Lincoln, believed would be certain electoral defeat, he told one senator, “We may be defeated: we may fail, but we will go down with our principle.” Imagine Donald Trump saying such a thing.

Again and again he comes across as not only the smartest man in the room, but the wisest, cleverest, kindest, and least pretentious.

George Saunders, author of the Booker Prize–winning Lincoln in the Bardo (2017), a novel about Lincoln’s grief at the loss of his son, wrote to me of the pleasure he felt immersing himself in Lincoln’s life, so that today, “to read anything about him reawakens that … zone, or whatever. Someone just sent me a photo of his recently renovated Presidential desk. And I like how seeing that added just a bit to the idea of him that exists in my mind.”

The New York Times Book Review sometimes asks well-known authors whom they would invite to a dinner party if they could have any person, past or present. My dinner party would have just one guest. I would want Abe all to myself.

Mark Bowden’s latest book, Life Sentence, will be published in April