Did you go to Dickens World before it closed? Between 2007 and 2016, an industrial hangar in Chatham hosted a theme park inspired by Charles Dickens’s London with animatronic rats, a Great Expectations flume ride and a children’s play area called Fagin’s Den. People who went give me differing assessments ranging from “actually so good” to “very, very strange”. Ultimately, money and visitors eluded it.

This was not the first reproduction of an ersatz Dickensian London. In this brisk book Lee Jackson uncovers a long and dubious tradition of previous Dickens Worlds. Take, for example, the Dickens Bazaar of 1888 that was erected inside Holborn Town Hall with stalls resembling locations from the great author’s works, from the Old Curiosity Shop to Peggotty’s boathouse. What is it about Dickens that makes people want to create his fictionalized city in three dimensions? And does historical accuracy matter?

Dickensland may be styled as a history of Dickens’s London, but it is not a walking tour (the author has already written a book of that kind). Instead, Jackson has crafted a droll, enigmatic ride through the 150-year-old phenomenon of Dickens tourism and its relationship with imagination. He charts the biographies of real places to show how they acquired a Dickensian lacquer; how “custom and practice, and perhaps a little exaggeration and wishful thinking, can create literary shrines”. Many of his chosen shrines have been demolished, meaning they too have passed into the realm of make-believe.

A droll, enigmatic ride through the 150-year-old phenomenon of Dickens tourism and its relationship with imagination.

Documented Dickens tourism began in 1866 when Louisa May Alcott, the author of Little Women, visited the old Kingsgate Street in Holborn in search of the home of Martin Chuzzlewit’s Mrs Gamp. By the 1880s, a decade after Dickens’s death, the tumbledown street exploded with attractions based on the now relatively obscure novel and its characters. At the end of the century visitors could even get a “Dickens shave” at Poll Sweedlepipe’s “original” barbers.

It is worth dwelling on how odd this is. These are places where things did not actually happen, because Dickens wrote fiction. Yet he did so with such a vivid, cinematic fixation on places — think of Satis House, the court of Chancery, the Marshalsea. With the addition of Phiz and George Cruikshank’s atmospheric, scratchy illustrations, the desire to seek out the author’s inspiration, and imagine the characters in situ, is understandable. Clearly there was an appetite for transparent absurdities.

In the 1880s the owners of the George Inn in Southwark, a building with no noteworthy connection to Dickens, would show visitors the “actual room” where Mr Jingle from The Pickwick Papers had stayed. It is the late 19th-century equivalent of queueing up at King’s Cross station in Hogwarts robes to pose with Harry Potter’s trolley.

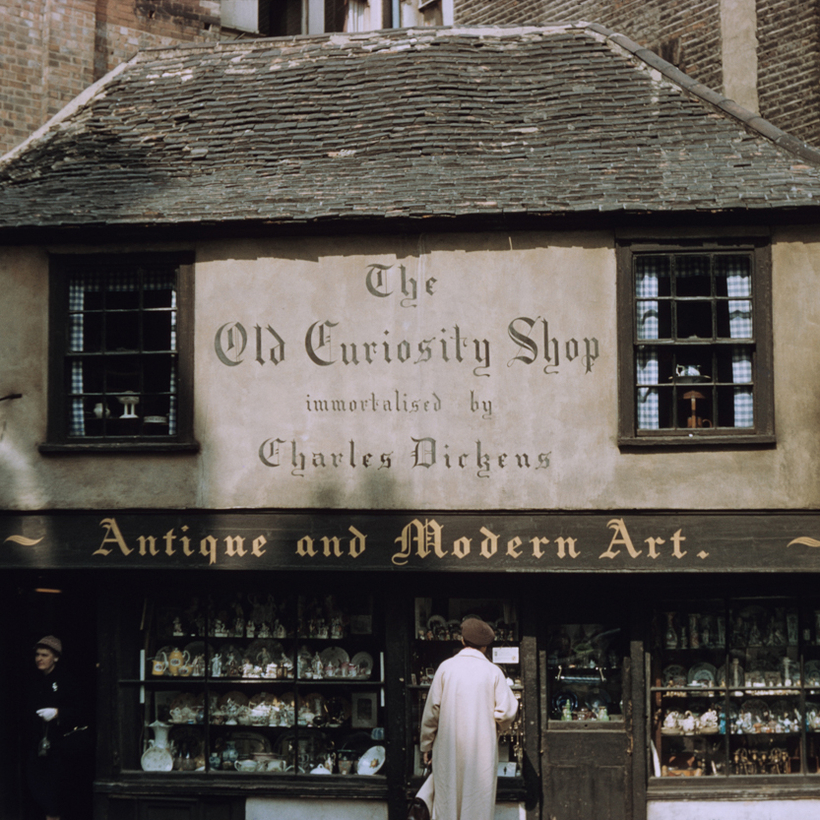

“Manufactured authenticity,” Jackson observes, “can prove very appealing.” In early decades the most popular Dickens destination was the Old Curiosity Shop, a ramshackle building on Portsmouth Street, near Lincoln’s Inn Fields, that still stands. It had “not the slightest connection to the novel, nor its author”, yet pronounced its non-existent credentials so extravagantly that it became a hit with tourists.

It was so recognizable that a full-size replica of it was built for the “Merrie England” zone at the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition in 1933. The shop “was always a fake, but an excellent one”; it looked the part. Jackson presses the point that in the public imagination “Dickens’s London” increasingly blurred with a much older Tudor London.

At the end of the 19th century visitors to the old Kingsgate Street in Holborn could even get a “Dickens shave” at Poll Sweedlepipe’s “original” barbers.

The late 19th century was the first era of commemorative plaques and, as Jackson writes, heritage sites “have a curious habit of producing more heritage”. By the 1890s, nostalgia for a disappearing Dickens’s London was already taking hold. Jackson argues that the specter of living history at risk is what “validated and valorized” sites such as 48 Doughty Street, Dickens’s home between 1837 and 1839, which became the Dickens Museum in 1925.

Inevitably, the desire for preservation would collide with the drive to modernize the metropolis and clean up its slums. As a writer, Dickens was drawn to the outdated and the filthy. In 1902, Kingsgate Street was demolished as part of the creation of two grand boulevards. One possible name for the new streets that became Kingsway and Aldwych was Dickens Avenue. Yet London planners were trying to escape these associations because Dickens’s London “had come to stand for precisely what the council was trying to erase: the slum, the decrepit house, the narrow street”.

Today, a plaque of mysterious origin sits just off London Bridge commemorating “the scene of the murder of Nancy” from Oliver Twist. However, Jackson, with eyebrow cocked, explains that not only was London Bridge replaced in the 1960s, Nancy is not even murdered on London Bridge in Dickens’s novel. The plaque actually references her death in the 1968 musical film adaptation. Evidently there is a reductive aspect to literary tourism: “Something fundamental may be lost in these endless copies of copies.”

I would have been happy to read about the plethora of places in Kent with Dickens associations, something Jackson rules out to focus on the capital. If an (admittedly interesting) pub in Chigwell can get a chapter, why not Rochester? Nonetheless, Jackson is a good-natured guide, skeptical but not pedantic, learned but unpretentious. He is just as comfortable discussing The Muppet Christmas Carol as he is David Lean’s Great Expectations.

Most importantly, he keeps returning to the novels, where characters such as the stultifying landlord John Willet in Barnaby Rudge ironically remind us of the dangers of living in the past. If you never made it to Dickens World, you can take comfort in Jackson’s conclusion that the Dickensian city of our imagination is bigger and “more capacious than any particular site or memorial”.

James Riding is a London-based writer