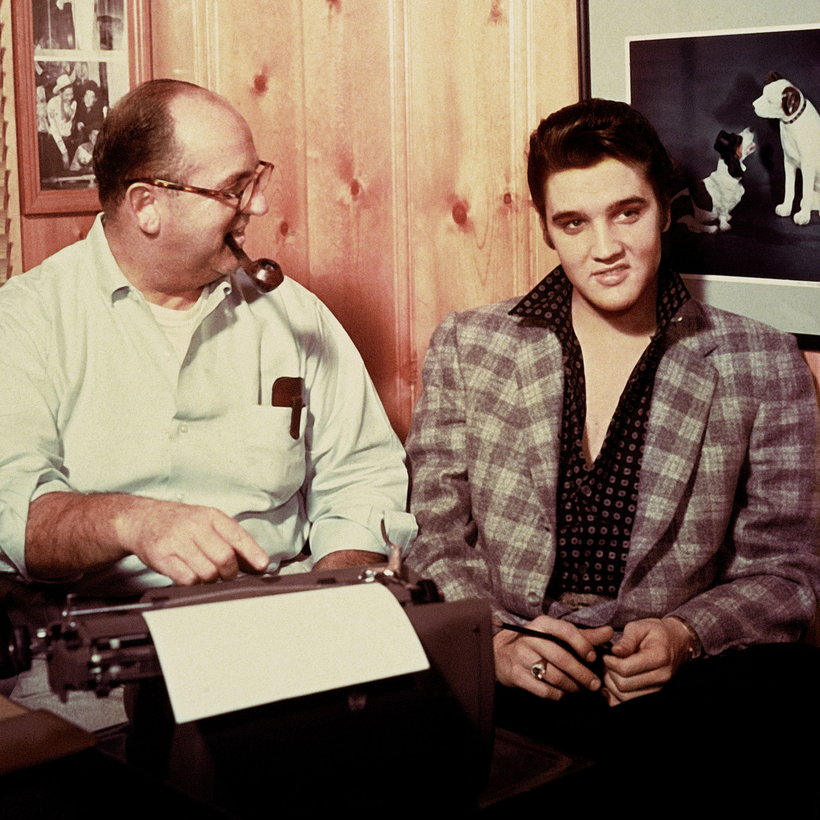

In recent years, debate has opened up about Colonel Tom Parker and his influence over his most prized and famous client: Elvis Presley.

It has long been accepted that he was a cigar-chomping malevolent leech who manipulated the King and controlled his every breath. Baz Luhrmann’s 2022 film further perpetuated the caricature of Colonel Parker (played by Tom Hanks) as the scoundrel juxtaposed to the cherished star (Austin Butler) forever ensconced in pop-culture sainthood. It was this installment in the ongoing, misinterpreted narrative that prompted my new book with Greg McDonald, Elvis and the Colonel: An Insider’s Look at the Most Legendary Partnership in Show Business.

Greg has spent most of his adult life silently lamenting the stories that vilified Parker, knowing that those who spun them weren’t aware of what necessitated the Colonel’s decisions, what he actually did for his client, and who he was behind the forward-facing persona. In this book, Greg and I sought to present another perspective, another way to view the renowned manager—as one who willingly became the heavy in order to ensure his client and friend achieved his dreams and survived the onslaught of fame and fortune that threatened to destroy him.

A Tip of the White Hat

Before he got to the top, Parker rode the rails as a hobo, sailed around the world in the merchant marine, served in the U.S. Army, and spent a decade as a traveling carny perfecting his act before meeting Presley in 1955. He understood human behavior and learned how to squeeze a nickel out of all of it, making him the perfect power behind the entertainment throne.

Parker, who was born in 1909, arrived in the U.S. a penniless immigrant from the Netherlands who overcame a language barrier and battled discrimination and bias; yet he came to befriend U.S. presidents and C.E.O.’s, and he created a cultural icon for the ages who generated $4 billion in his lifetime, all the while managing to keep a relatively low profile.

Parker’s mantra was “The artist always wears the white hat,” meaning the artist’s image must be preserved at all costs, and it was that firmly held philosophy that led him to take the hits to his reputation and his relationships. Greg was privy to many of the scenarios that spun Elvis in wild directions and created messes the Colonel had to scramble to clean up.

For example, many fans and critics hold the mistaken belief that Parker’s greed was the cause of his client not landing the lead role in the 1976 remake of A Star Is Born. The truth is, when Presley learned that Barbra Streisand would get top billing on the $6 million picture and her then boyfriend, Jon Peters, would be calling the shots as a producer, he balked.

“You know, Streisand has been known to take control of a picture, and I don’t know if I can deal with that,” Presley told his bodyguard Sonny West at the time. “And that hairdresser boyfriend of hers might end up directing it, and I might have to slap the shit out of him.”

So, Presley turned to Parker to help him save face. Parker did so by putting Presley’s fee out of the ballpark, so Presley didn’t have to say no but could simply intimate, “You can’t afford me.” The fans smarted because the movie, which ultimately cast Kris Kristofferson opposite Streisand, raked in $80 million at the box office and was the second-highest-grossing film of the year (behind Rocky and ahead of King Kong). They blamed Parker’s haggling for the missed opportunity.

Tom Parker’s mantra was “The artist always wears the white hat,” meaning the artist’s image must be preserved at all costs.

Parker also shouldered the blame for selling Presley’s back catalogue to RCA Records for a mere $5.4 million in 1973. Parker did not want to pursue the deal, because Presley’s royalties generated about $500,000 a year—he saw this nest egg as his client’s “annuity” and something that shouldn’t be messed with. Yet Presley pressed the issue because he needed a quick influx of cash for the payout in his impending divorce from Priscilla. He also said his father, Vernon Presley (who had dropped out of eighth grade and should never have handled Presley’s business affairs), had already started negotiations with the label, so they couldn’t walk away.

When negotiations hit a snag, and Parker realized that father and son were practically giving the catalogue away, he stepped in to broker a more equitable deal. This shortsighted money grab was neither induced nor endorsed by Parker—but he took the hit for the poor judgment.

Parker also faced regular challenges due to Presley’s habit of spending more than he earned. At the end of his life, Presley’s estate amounted to about $1 million in checking, nothing in savings, and $4.9 million in assets. The cash-poor estate had mounting bills, and keeping Graceland functional and operational was expensive, placing his empire in jeopardy.

“You know, Streisand has been known to take control of a picture, and I don’t know if I can deal with that.”

While the world was mourning the death of Elvis Presley on August 16, 1977, Parker set his grief aside to “take care of business.” He knew there’d be a big run on Presley records and merchandise, and he placed key calls and made deals to ensure that all contracts were legitimate, supply chains were in place, and demand could be met. He implored RCA to press as many Elvis records as possible, even getting them to re-activate a pressing plant in England slated for closure. They pressed millions of records, and much of his back catalogue went gold or platinum. Anything attached to Presley literally flew off the shelves.

More importantly, Parker set up a line of merchandise and licensing deals to stop bootleggers from manufacturing or commercially exploiting Presley’s image and likeness. Even in the wake of the loss of his friend, Parker was looking out for the Presley family and Elvis’s legacy—arguably, just as he always did.

Parker’s handiwork in the immediate aftermath of Presley’s death brought the estate ledger back into the black in a matter of a year. Not only did he save the estate, but he made it what it is today—according to Rolling Stone, Elvis Presley Enterprises has a net worth of half a billion dollars, and Graceland greets approximately 600,000 people a year.

While Parker’s less-than-glowing image served his client’s interests until the end, it’s high time for his black hat to be switched to white.

Marshall Terrill is a co-author, with Greg McDonald, of Elvis and the Colonel: An Insider’s Look at the Most Legendary Partnership in Show Business, out now from St. Martin’s