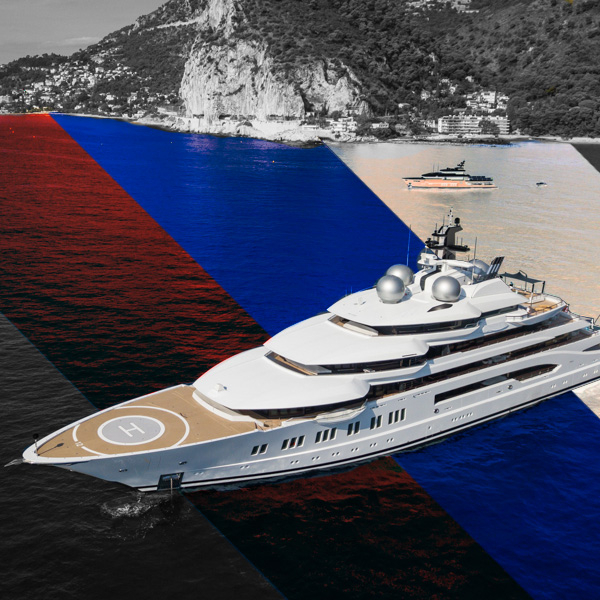

Hang around the San Diego Bay harbor long enough and you just might see it: a $300 million super-yacht cruising by, now and then sounding a horn that has reportedly “scared the hell” out of local fishermen.

Meet the Amadea.

U.S. authorities seized the 348-foot-long boat off the coast of Fiji in June 2022. The yacht, they feared, was on its way to Russia, beyond the reach of Western sanctions. Instead, the seized vessel raised a U.S. flag, changed crew, and changed course for San Diego.

The Amadea is tricked out like a Versailles on water, complete with helipad, infinity pool, and a custom baby-grand piano with 24-karat-gold pedals and hinges. That the owner is a sanctioned Russian billionaire with close ties to Vladimir Putin is not in dispute. The question is: Which one?

On March 2, 2022, the U.S. Justice Department launched its elite Task Force KleptoCapture, with the aim of targeting Kremlin-controlled oligarchs, confiscating what President Biden, in that year’s State of the Union address, called their “ill-begotten gains,” and giving the proceeds to Ukraine.

Twenty months later, the U.S. has handed over to Ukraine a mere $5.4 million from $500 million worth of “seized or restrained” assets, according to a U.S. Treasury spokesperson, while the U.K. and the E.U. have sent nothing, which all begs the question: Are sanctions working?

“Super-yachts are really shiny symbols of oligarch wealth—conspicuous and mobile in a way that speaks to how the oligarchs have long been free to move around large amounts of money across borders,” says Helen Taylor, a senior legal researcher at Spotlight on Corruption. “They became very desirable targets for sending a message.” Seizing the Amadea “shows law enforcement flexing its muscles, and their ambition of pinning down wealth wherever it goes.”

But, Taylor says, “it’s also symbolic of some of the broader challenges,” such as determining the true owner. “Then there is maintenance,” she adds. “It’s one thing to take control of a super-yacht, but it costs millions of dollars a month to maintain, with the risk that this bill may be left for the taxpayer to pick up.”

Seizing the boat in international waters was simple enough. Proving ownership is more complicated. “The absence of transparency makes it very hard to go after oligarchs’ assets,” says kleptocracy expert Louise Shelley, the founder and executive director of the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center and chair of the Schar School of Policy and Government, at George Mason University. “It’s also expensive to do the research to provide the financial evidence needed in court.”

Putin-linked oligarchs bury asset ownership in “Russian-doll schemes where one offshore company is owned by another, all in different jurisdictions,” says kleptocracy expert Ilya Zaslavskiy. “Western law enforcement should be able to uncover beneficial ownership quickly with a court order.” That they can’t is “mind-boggling.”

Some experts note that sanctions take time because the U.S. is a law-based nation, and asset forfeiture must go through the courts. Others say oligarchs have found loopholes and work-arounds to evade sanctions. At the same time, third-party countries break sanctions by bringing luxury consumer goods into Russia and taking natural resources out, such as oil.

Most experts say that sanctions need to expand to include both more individuals and Russian-sovereign bank accounts. And all agree that with the White House’s attention now focused on the Israel-Hamas war, Putin has only gotten bolder, making better enforcement more necessary than ever.

To that end, on November 28, Senators Sheldon Whitehouse and Lindsey Graham, together with Representatives Joe Wilson and Steve Cohen, introduced the bipartisan Asset Seizure for Ukraine Reconstruction Act. The bill would allow the Department of Justice to seize the assets of sanctioned Russian oligarchs faster through existing administrative forfeiture processes and transfer the proceeds from those assets to Ukraine.

The Amadea is tricked out like a Versailles on water, complete with helipad, infinity pool, and a custom baby-grand piano with 24-karat-gold pedals and hinges.

The Amadea had been touted as KleptoCapture’s biggest trophy. “This yacht seizure should tell every corrupt Russian oligarch that they cannot hide—not even in the remotest part of the world,” Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco said in a statement.

On October 23, the U.S. government filed a civil-forfeiture complaint claiming the yacht is beneficially owned by Suleyman Kerimov, a Dagestan-born, U.S.-sanctioned gas-and-gold mogul and Russian senator whose estimated net worth is $10.7 billion. Kerimov, who was one of the oligarchs by Putin’s side the day Russia illegally invaded Ukraine, denied ownership.

Also on the morning of October 23, another Russian billionaire, Eduard Khudainatov, who is sanctioned in the E.U. and Ukraine but not the U.S., claimed ownership of the Amadea and filed a 41 (g) motion in the Southern District of New York to get it back. The feds in turn filed a counter-motion, arguing that Khudainatov’s case is “meritless,” filed in the wrong district, and “should be denied in its entirety.”

An ex-head of Rosneft, Russia’s state oil company, Khudainatov has reportedly been close to Putin since working on his 2000 presidential “campaign.” Khudainatov also claims to own two additional yachts, worth around $1.2 billion in total. Those are the $700 million Scheherazade, a mega-yacht linked to Putin that the Italian government seized in May 2022, and the $600 million Crescent, which is allegedly owned by Putin pal Igor Sechin, Rosneft’s current C.E.O. Khudainatov, who is worth an estimated $2 billion, according to Forbes, is so close to Sechin that their kids live next door to each other in Russia.

Khudainatov also reportedly owns both the Independent Petroleum Company, known as NNK, which had been sanctioned by the U.S. for sending more than $1 million worth of petroleum products to North Korea, and Coalstar, a Russian coal company.

The feds say Khudainatov is a “clean, unsanctioned straw owner” who is pretending to be the Amadea’s owner in order to help Kerimov evade sanctions. Khudainatov’s American lawyers, Adam Ford and Renée Jarusinsky, insist the seizure was “unlawful.” In court filings, which refer to the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation,” they describe their client as a “long-time boating enthusiast.”

A source involved in other sanctions cases says the government may have been “overzealous in seizing yachts” following Biden’s State of the Union address. “This was a movable asset, so they grabbed it and thought they’d figure it out later. Now they are committed to a theory they’re stuck with.” The government would have more money to show for its efforts, the source says, if it had “done nothing instead of spending money seizing and maintaining yachts.”

But another inside source says the U.S. will be reimbursed for upkeep costs when seized assets are forfeited and sold—and that “there is nothing new, unusual, or unexpected here.”

“We said all along that the straw owner was paid off to pretend that the Amadea was his boat, and that’s exactly how it is playing out,” the source says. “The 41 (g) motion will fail because there’s already a legal mechanism to resolve the dispute in the forfeiture suit. ”

Earlier this week, Khudainatov’s lawyers filed a claim, challenging the government’s forfeiture complaint, in United States District Court, Southern District of New York. “In contrast to the conjecture and false statements that led to the unlawful seizure of the vessel, this claim cements the fact that Mr. Khudainatov is, and has always been, the ultimate beneficial owner of the Amadea,” Ford said in a statement.

But as Gary Kalman, the executive director of Transparency International’s U.S. office, says, beneficial ownership is not just about who owns what on paper. It’s about who has control of companies and the assets they own.

Putin-era oligarchs have a history of trading and masking assets to help each other evade sanctions, says Zaslavskiy. In fact, he adds, “oligarch” is an outdated term. “They are Kremligarchs. They may appear to be wealthy tycoons in the West, but they are merely wealth handlers for the Kremlin.”

Invisible Assets

Western powers once thought of kleptocracy and corruption as something that happened in other, less developed countries. But since the collapse of the Soviet Union, capital flight, from Russia, China, and other countries, has soared into the trillions. The money is stashed in hidden offshore accounts by the West’s so-called enabling class of lawyers, accountants, P.R. experts, art dealers, and real-estate brokers who launder dirty money, strengthening autocracies while undermining democracies from within.

When Putin took power, in 1999—Yeltsin appointed him president in exchange for immunity from prosecution for corruption—he demanded his oligarchs raise their profile abroad to further Russian foreign policy, and the oligarchs obliged. They spent billions on philanthropy, sports franchises, and political donations to buy influence, and it paid off.

When sanctions finally hit, some had already moved their money, suggesting that they may have had advance notice of what was to come, whether via leaks or spies. Roman Abramovich, for example, transferred real estate and a majority share of his billion-dollar art collection to one of his ex-wives shortly before new rounds of sanctions were announced. Oleg Deripaska managed to get Rusal, his Russian aluminum company, off the U.S. sanctions list in 2019.

The U.S. government finally woke up to the threat of corruption in June 2021, when Biden issued a national-security memo that called fighting corruption a “core” U.S. national-security interest. Ironically, perhaps, the big items oligarchs used to gain influence and impress the West—yachts, jets, mansions—were actually the first things to be seized, because they were so visible. How much is invisible, hidden in offshore accounts? The truth is, no one really knows.

“At the start, the focus was on more ostentatious assets,” says David Lim, co-director of the KleptoCapture task force. “We wanted to make sure the world knew we were serious about making the lives of people supporting the Russian regime as uncomfortable as possible.”

More recently, he says, the focus has shifted to “the facilitators … the procurement networks … the professional money managers, lawyers, and others who take advantage of U.S. institutions to evade sanctions. But it takes time. We are at it, burning the midnight oil to move as quickly as possible.”

Capital flight, from Russia, China, and other countries, has soared into the trillions. The money is stashed in hidden offshore accounts by the West’s so-called enabling class of lawyers, accountants, P.R. experts, art dealers, and real-estate brokers.

Co-director Michael Khoo says, “It’s not all obvious things that the world can see, like yachts and jets. There is a lot of money out there that we are tracking and investigating—billions of dollars. You notice when the Amadea pulls into San Diego. But we aren’t just going after the most visible assets. We are doing our small part to bring this war to an end and to empower the Ukrainians.”

Some say it’s too little, too late. The $5.4 million in forfeited assets that U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken brought to Ukraine last September is “peanuts,” says Daria Kaleniuk, executive director of the Anti-Corruption Action Center, based in Kyiv. Why not send the $350 billion of Russia’s Central Bank reserves abroad that were frozen after the invasion to Ukraine?, she asks. It’s an idea that has been suggested by others, including American-born British investor Bill Browder, sometimes referred to as Putin public enemy number one. But as even Kaleniuk notes, there is currently no legal basis to do so unless Russia and Western nations are officially at war.

For now, says Elina Ribakova, a director of the Kyiv School of Economics’ international program, the goal of sanctions remains “a moving target.” At first, officials hoped sanctions would help prevent war. Then they hoped to stop it. Now, they hope, “more realistically, to undermine Russia’s ability to fight the war,” she says.

Part of the problem, Ribakova says, is that the West needs to “clean up the global financial system and the offshore enablers in order to get to the bad actors, or the implementation of sanctions becomes more challenging.”

But the feds do have some laws on their side. “Beneficial ownership” is defined as either owning 25 percent of an asset or evidence that an individual controls an asset. “Beneficial ownership goes beyond simple ownership. It’s about who controls the asset, through side relationships,” says Kalman.

And sanctioned individuals have felt the pinch. In October, billionaire Mikhail Fridman, for example, was denied a request to pay his British staff, including drivers, housekeepers, and chefs, to maintain his luxury, $80 million mansion. He has since moved back to Moscow, according to reports.

“Part of the purpose of sanctions is to take a stance and say the U.K. economy is open, but it is not a safe haven for dirty money,” says Taylor, who notes that “a lot of progress has been made.” The question is: Where do we go from here?

“Sanctions hurt at the outset, but the Russian economy has, to a certain extent, stabilized, and the oligarchs are finding alternative ways to fund their lifestyle using third countries more welcoming of their money,” Taylor says.

There may be another reason for America’s lack of commitment to the sanctions program: fear of success.

“What happens if we get enough money to ramp up production of weapons, and it’s enough for Ukraine to win?,” Kaleniuk says. “The U.S. has no strategy for what will happen if Russia loses.”

Jennifer Gould covers real estate and food for the New York Post. She is currently working on a book about covert foreign influence in the United States