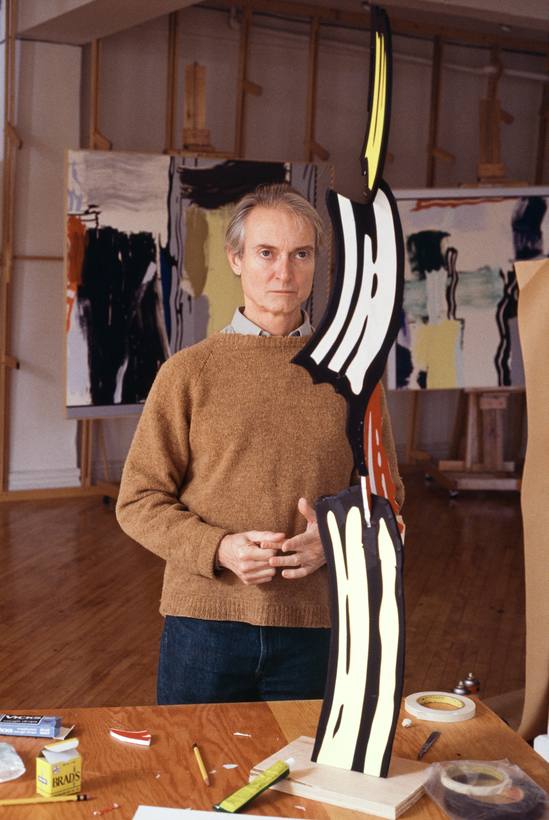

The twin sculptures that make up Tokyo Brushstroke I & II show off a Roy Lichtenstein quite different from the one we know—the artist who famously hijacked the comic-strip style in canvases that projected witty, irony-drenched messages. Tokyo Brushstrokes, towering as much as 33 feet above a field outside the Parrish Art Museum, in the Hamptons, is alive with kinetic energy, a celebration of what sculpture can do. At the top of one of the two sculptures, a paint-like sweep, blue and white and frozen in aluminum, almost merges with a sunny Long Island sky. A palette-like shape tops the other. As Tokyo Brushstrokes awaits a restoration, it symbolizes something else: the growing need to repair outdoor sculptures made since their renaissance in the 1960s—at a frequency and expense many artists and owners may not have anticipated.

The Parrish is planning its restoration during the season of Lichtenstein’s 100th birthday (celebrated five weeks ago, on October 27), which the Parrish itself and other museums and galleries have already fêted with exhibitions. The Albertina, in Vienna, opens its centennial show on March 8; the Whitney will wait until 2026 for a massive retrospective.