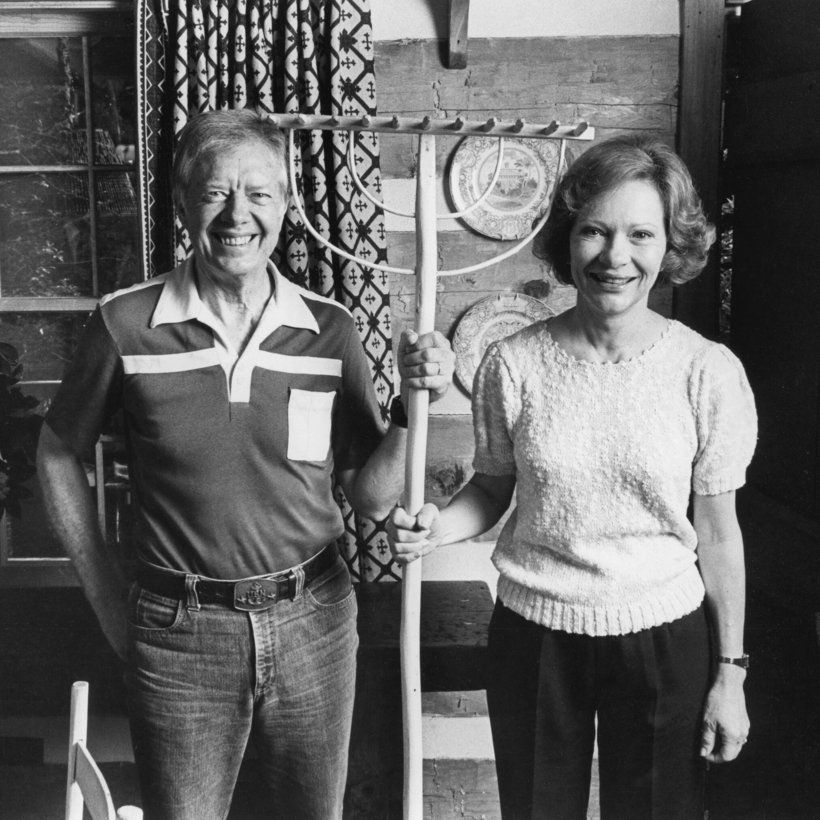

In his memoir A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety, former president Jimmy Carter described what he called the “worst threat” to his marriage to Rosalynn, which lasted 77 years, until she died in November. Carter remains in home hospice care.

It happened when they tried to write a book together.

“I write very rapidly and Rosalynn … writes slowly and carefully and considers the resulting sentences as though they have come down from Mount Sinai carved into stone.... We had constant arguments and could communicate with each other only through harsh emails. When we decided to cancel the project and return the publisher’s advance payment, our editor came to Plains and proposed that he divide the controversial paragraphs between us.... In the book, each of these paragraphs is identified by a ‘J’ or an ‘R’ and our marriage survived.”

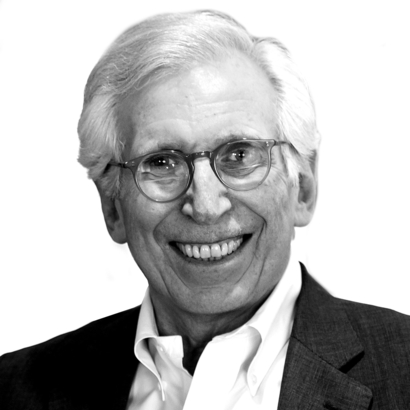

I was that editor.

In 1986, when I was at Random House, the Carters’ literary agent, Lynn Nesbit, sent me a brief proposal for a book about how to make best use of the health and longevity that 20th-century medicine had enabled. The Carters were in their 50s when he was defeated for re-election six years earlier and had returned to Plains, facing financial problems and an undefined future. They became increasingly admired for their work in human rights and global health, and with Habitat for Humanity.

They also chose to write books. After their respective memoirs of the White House years, this project was up next.

My notion was to expand the focus of a book that came to be called Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life.

The writing was clearly going slowly, so I went to Plains for an all-in editorial session. It is not an understatement to call the Carters’ home and lifestyle modest. We spent hours at a dining-room table surrounded by papers, ate lunch in the kitchen, said grace, and were served sandwiches by the housekeeper, Mary Prince. Prince had been wrongly convicted of murder and was rescued from prison by the Carters, who fought for her release while in the White House.

“We had constant arguments and could communicate with each other only through harsh emails.”

One evening, on the television in their bedroom, we watched President Ronald Reagan squirm his way through a speech explaining how his administration had violated the law by sending arms payments from Iran to right-wing Nicaraguan militias.

“Whoa, that looks bad,” I recall Carter observing about the political dilemma his successor was in.

But the book project was clearly going slowly. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Carter later said: “All of Rosalynn’s bad characteristics came out during the writing of this book, and I guess mine did, too.”

“We were so frustrated with each other about it that we couldn’t even talk about it,” Rosalynn said. “It was not just frustrated, it was angry.”

I never saw any testiness between them, although once, while working on another book with religious themes, the former president didn’t like my edit and let me have it, offering me a glimpse of what Carter anger could look like. (I recovered.)

From some margin of my editorial playbook, I devised the idea of separating the writing by paragraphs with initials attached. In my New York apartment, on my own dining-room table, I splayed the pages and put them together in a form the Carters could work with.

The book became a solid best-seller when it was published, in May 1987. Over the years, I would see mention of the marital tension, sometimes with my name included, sometimes not. Carter did refer to me from then on as a “publisher, editor, referee, and friend.” And on more than one occasion he told me that I had “saved” the marriage, which he would usually say with a smile.

I gradually decided that it must be true. Even Vogue’s account, when Rosalynn died, of what it called their “achingly sweet love story” had a version of the episode.

I went on to publish two more books with Rosalynn, one on mental health and another on caregiving.

And I worked with the former president as his writing career flourished. We turned his Sunday-morning homilies at the Maranatha Baptist Church into an explanation of his religious commitment. He also wrote a children’s book, illustrated by his daughter, Amy, who is an artist, and he persuaded me to publish a book of his poems, which to my astonishment was well received and became a best-seller.

One of the poems, widely reproduced, was about Rosalynn. It closes this way:

With shyness gone and hair caressed with gray

her smile still makes the birds forget to sing

and me to hear their song

Peter Osnos is a journalist and the founder of PublicAffairs. He is the author of several books, including An Especially Good View: Watching History Happen, and he writes a Substack column called Peter Osnos Platform