When I disembarked at the Freistadt train station in October 2021, I was greeted by an empty platform and the twinkling of lights far in the distance. There were no taxis in the small Austrian village at eight P.M. on a Sunday, so, carrying my suitcase and laptop bag, I walked to my hotel in town, guided by the light of my phone’s map.

Herr Heinz Hueber greeted me the next morning. Tall, gray-haired, and distinguished-looking, Heinz is the great-grandson of Albert Ballin, the managing director of the Hamburg-American Line. Ballin, a German-Jewish business wizard who rose from a childhood of crushing poverty, helped facilitate the mass exodus of at least 1.5 million Jewish emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States in the years before World War I and is part of the story I tell in my new book, The Last Ships from Hamburg.

I had spoken to Heinz on WhatsApp before the pandemic, and we had agreed to arrange a meeting. Then the coronavirus shut down air travel, closed borders, and shuttered archives. My book project had ground to a halt, and I had to rely on secondary matter, as well as a 2019 visit to Hamburg in which I was granted rare access to the Hamburg-American Line archives.

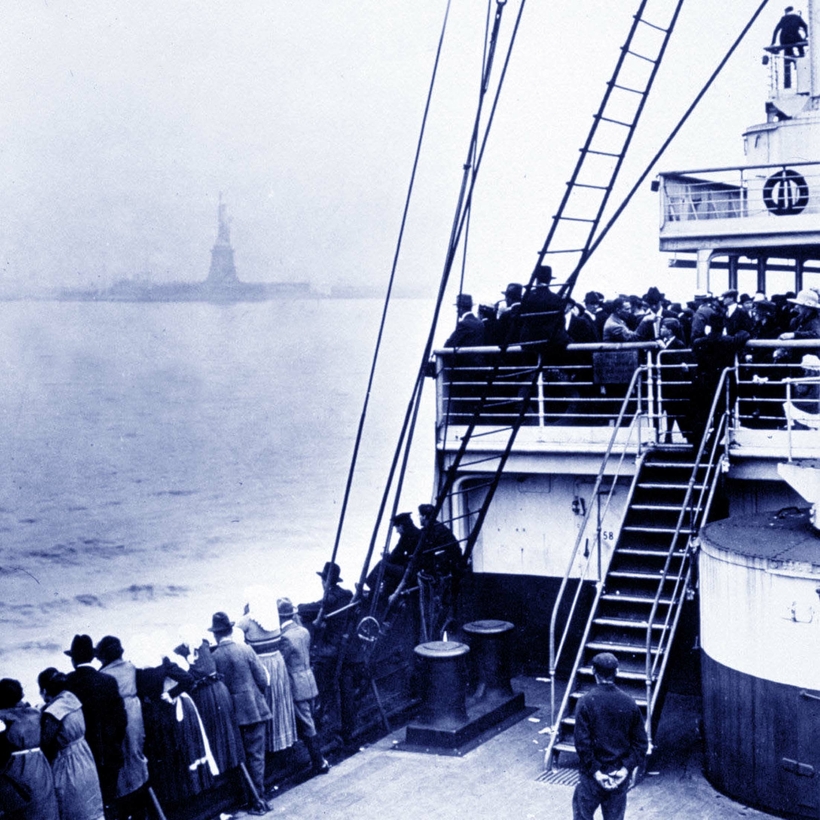

I learned a lot about the operations of the Hamburg-American Line, which derived much of its profits from the immigrant trade. Its outwardly glamorous ships carried hundreds of thousands of Jews escaping Czarist Russian persecution at around $30 a head. Under Ballin’s stewardship, it grew to be the largest shipping line in the world between 1881 and 1914. But I wanted to know more about the man himself, of whom little was known in America, even though his shipping empire had more impact on America as we know it today than the Mayflower.

Heinz drove me through the Austrian Alps to the Hueber residence, a white-stone cottage nestled in a sunlit Alpine garden. Hanging in the living room was a portrait of Albert Ballin, dressed in a dark suit, his warm brown eyes twinkling through a pair of gold-rimmed pince-nez glasses.

“We see him every day,” his great-grandson, who is in his mid-70s, said. “We are proud of what he did, and proud of how he was to his family, to his friends, how social he was. He was not only a businessman.”

This portrait, like so much of Ballin’s legacy, was kept out of sight for decades in order to survive the wrath of the Nazis. To them, Ballin, a German patriot until his death in the last days of the First World War, was not a hero, a family man, a self-made genius. Rather, he was a traitor, a capitalist, and a Jew.

After enjoying a delicious homemade Sacher torte, Heinz, his wife, Ingrid, and I talked for several hours. He never met his great-grandfather, but he clearly loved him, and when talking of his great-grandfather’s death from overwork, Heinz started crying.

A committed pacifist, Ballin worked hard behind the scenes to stop a war between Germany and Great Britain by leveraging his relationship with his close friend Sir Ernest Cassel, another German Jew who served as a private financial adviser to King Edward VII. The naval arms race particularly troubled Ballin. At their last meeting, in 1914, Winston Churchill, then the new First Lord of the Admiralty, reportedly told Ballin, “My dear friend, don’t let us go to war.” Ballin’s efforts proved futile, and his worst nightmares came true.

Ballin died on the eve of the 1918 armistice, his health and shipping company in ruins due to the seizure of most of its ships by the Allies. In the years after his death, the United States passed new, racially motivated immigration laws that cut off Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe. This series of events doomed millions of Ballin’s co-religionists, eventually trapping them in the grips of Hitler’s “Final Solution.” Soon after coming to power in 1933, the Nazis systematically erased Ballin’s name and legacy from the Hamburg-American Line.

Ballin’s grandchildren realized they had to do something to protect his memory from destruction. All of his papers and photos had been stored in old steamer trunks, all marked with the name “Albert Ballin.” To prevent them from being identified with a Jewish businessman, his grandchildren removed the name, just leaving the initials A and B, and kept the trunks hidden in their Hamburg attic.

Miraculously, the family home escaped the Allied firebombing. After the end of World War II, their trunks and letters were moved to the home of Ballin’s granddaughter Ursula Hueber in Austria, and they have remained in her family’s possession ever since.

Back at the Hueber residence, I took one last look at Ballin’s portrait while Heinz, who is Ursula’s son, went into his office. He came back with two volumes. One was a transcribed set of letters to and from Albert Ballin. The other contained the letters of Irmgard Ballin, his adopted daughter.

Then Heinz dropped me off at the Freistadt station. This time, it was daylight, and my luggage was heavier—I was now the steward of miraculous cargo, destined for my study in Philadelphia.

Steven Ujifusa’s The Last Ships from Hamburg: Business, Rivalry, and the Race to Save Russia’s Jews on the Eve of World War I is out now from Harper