By some measures, the reconstruction of the old Domino Sugar refinery on the Williamsburg waterfront makes no sense at all. It was expensive to build. It contains not a single apartment, let alone anything affordable that might ameliorate New York City’s housing crisis. And it is not a cultural facility, which is what so many enormous and obsolete industrial structures of landmark quality end up becoming these days, in the manner of the Tate Modern, in London, or Dia Beacon, upstate, or Mass MoCA, in the Berkshires. The just completed Refinery at Domino is now, of all things, an office building, which you would think is the last thing the city needs today, considering that around 20 percent of its office space is currently vacant.

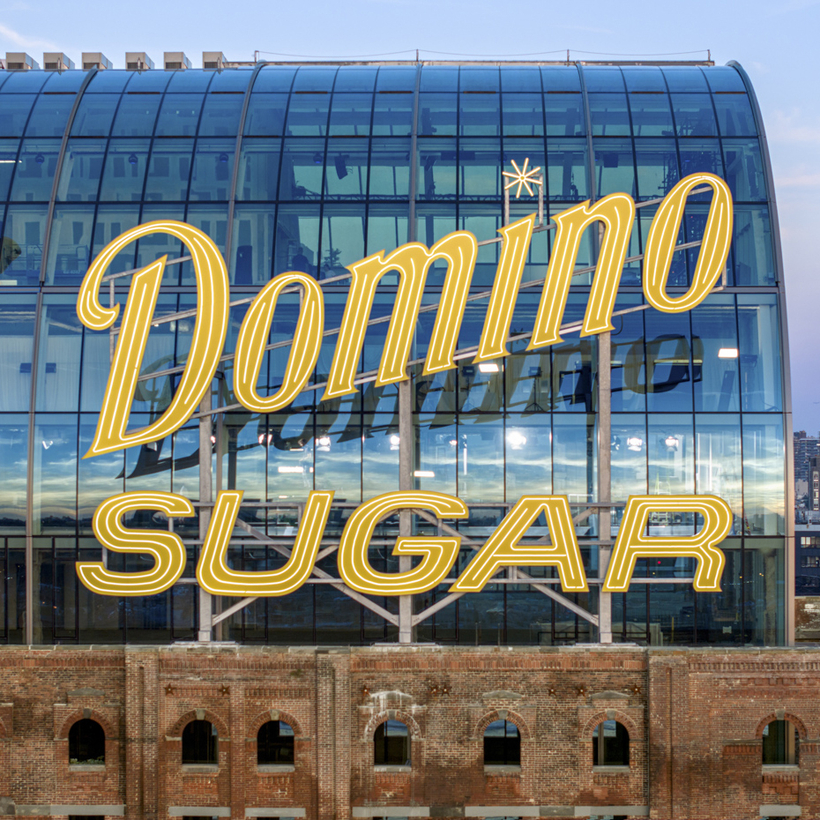

But this is the best piece of new architecture along the New York waterfront right now, and, arguably, the most important, which tells you how wrong the common wisdom can be. As a work of design, it’s the most compelling juxtaposition of old and new that the city has seen since the completion of the Hearst Tower, in 2006. There are some curious similarities between Hearst and Domino, in fact. In much the same way that Norman Foster, Hearst’s architect, used a structurally bold glass tower as a counterpoint to the grandiose base designed by Joseph Urban in the 1920s—hoping that sleek new architecture would help purge the Hearst Corporation of its founder’s pomposity—Vishaan Chakrabarti, of the Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, the architect for Domino, had to enact an even greater feat of exorcism as he worked to craft something meaningful for 21st-century New York out of the remains of a 19th-century building that had been a harsh and oppressive working environment for an industrial corporation whose profits had come, in part, from enslaved plantation workers.

Chakrabarti had one thing going for him, however, besides the fact that the Domino refinery, even in its ruinous state, was one of the great brick structures of New York, a magnificent assemblage of Romanesque details, arched windows, and a 214-foot-tall brick chimney, one of those factories that leaves you in awe of the ability of Gilded Age oligarchs to create noble structures for mundane labor. His client was not the sugar company that had given up its Brooklyn refinery almost two decades ago but one of the city’s more enlightened real-estate developers. And therein lies the story of why turning the massive refinery into an office building may not be as crazy as it first seems.

The project was conceived by Jed Walentas, who runs Two Trees, the real-estate firm founded by his father, David, who became a billionaire by following instincts that were often contrary to those of other New York developers. David Walentas, one of the first developers to convert old buildings in SoHo into housing, operated by instinct, with a natural feel for the ebb and flow of the city.

In 1978 David took a gamble and bought an entire portfolio of old industrial buildings between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, which became Dumbo. Jed Walentas inherited his father’s iconoclasm, as well as a love of old buildings and an understanding that a good urban neighborhood is not a collection of sleek new buildings in the manner of Hudson Yards but an amalgam of new and old, of small and large, of public and private, of work and leisure.

A good urban neighborhood is not a collection of sleek new buildings in the manner of Hudson Yards but an amalgam of new and old, of small and large, of public and private, of work and leisure.

In time, the success of Dumbo put Two Trees on a solid enough financial footing that Walentas, who took over the company in 2011, could undertake his own big project and be spared the financial anxiety that his father had experienced over the 20 years it took for the company’s investment in Dumbo to pay off.

In 2012 Two Trees purchased the 11-acre Domino site for $185 million from a developer that had defaulted on its loans for the project, which at that point was to contain several apartment buildings arrayed around the old refinery. In the earlier scheme, the Domino refinery would have been converted into more housing as the central element of a plan involving a narrow waterfront park by the architect Rafael Viñoly.

Walentas then made his first unusual decision, which was to throw away Viñoly’s design and start anew. It was a big risk, since the plan had already received city and community approvals, and if it were changed, Two Trees would have to go through the long and complex city-approval process all over again. But the Viñoly plan was ordinary, the kind of thing that results from endless compromise, and Walentas was determined to build something different from most of what was already going up all over the Queens and Brooklyn waterfronts.

Walentas hired the architectural firm SHoP to produce something more striking, which Chakrabarti, then a partner at SHoP, did, adding an expansive open space on the riverfront that would become Domino Park; he also included a public square and more streets to continue the Williamsburg grid across the property. The trade-off in the new plan was that Two Trees wanted to build residential towers that were taller than what the older plan had called for, but also thinner, giving Williamsburg the potential for a dramatic skyline. And Walentas and Chakrabarti decided that the refinery, which was a city landmark, should become not housing but an office building, on the theory that if Williamsburg was attractive enough for young people to live in, it would be equally attractive to work in, and the technology and creative industries that had given Dumbo its commercial base would want unusual space on the waterfront in Williamsburg as well.

All of this was pre-pandemic, of course, and it remains to be seen how fast the space in the refinery will fill up; however attractive the idea of working in Williamsburg may be, offices everywhere are struggling. But the desire to work someplace other than your kitchen table is unlikely to become extinct, and Walentas has what may be the most important quality of all for a real-estate developer, which is patience.

He also has the other two requisites for a good developer: architectural taste and access to resources. He’s already made use of both of these in the initial residential buildings he’s had built around the refinery by SHoP, CookFox, and Annabelle Selldorf, all of which have been designed to conform with Chakrabarti’s master plan for the site, and in Domino Park, designed by Field Operations in a way that deftly melds together a waterfront promenade, handsome landscaping, activity space, and the old gantry cranes from the refinery, which have been moved to the waterfront and reimagined as monumental sculpture.

In the end, however, it is the old Domino refinery that is the heart and soul of the entire development, the aspect that gives this section of Williamsburg a name and an identity, and that will define it as different from every other new waterfront development anywhere in New York.

For the refinery, Chakrabarti took on the role of architect as well as planner and came up with a design that emerged out of a recognition that the enormous structure could not be easily adapted into a conventional modern building regardless of whether it contained apartments or offices. The arched windows in different sections of the 11-story-high brick façade didn’t line up, the floor heights were inconsistent, and there weren’t many floors left, anyway. The building had been altered so much over the years that little about it seemed to make sense other than as a sumptuous, brooding relic.

Chakrabarti decided to treat the old building as a shell, and to let all the original exterior walls stand as a vast, four-sided screen, leaving the arched windows as pure openings devoid of glass. He then erected an entirely new glass office building inside the old shell. The interior structure not only looks different from what surrounds it, it will function in a way that is equally distinctive: the Refinery at Domino will be powered entirely by electricity, making it, Walentas believes, the first all-electric office building in New York City.

The technology, of course, is invisible, but the drama of the structure itself is quite the opposite. The glass walls are set back from the original brick walls, almost floating inside the old refinery, and at the top a two-story barrel vault of glass that pushes above the original roofline. From across the river, it can look as if he had just dropped a bulbous glass roof onto the old building, and the effect is a bit discordant, but once you are close and you see that this is not a glass hat on top of a brick body but an entirely new structure of glass rising inside the old brick enclosure, the effect is both more powerful and more subtle.

Modern additions to old buildings are often problematic, and architects struggle with the question of how closely they should follow the original design. Should the architect strive to be so well mannered as to be almost invisible, as Kevin Roche was when he expanded the Jewish Museum on upper Fifth Avenue by precisely imitating every detail of the old Warburg mansion? Or should they be as bold as the very same Kevin Roche had been when, a few years before, he added slanted glass wings to the sides of the Metropolitan Museum? Or should they try to split the difference, as James Stewart Polshek did when he added a modern tower of masonry and metal to the back of the elegant glass box of 500 Park Avenue?

Most additions to historic buildings are on top of, next to, or behind the original building, and new and old face off against each other, sometimes with warmth, sometimes with hostility. At Domino, Chakrabarti has come up with another way altogether to deal with the question of the relationship of new and old, which is to build new inside the old, the two eras of architecture cohabitating. You see glimpses of the new structure through the open voids of the old façade’s windows, but then you see it pushing its way through the top, bursting out like new plant growth that has forced its way skyward.

This is not a glass hat on top of a brick body but an entirely new structure of glass rising inside the old brick enclosure.

The empty space in between the original brick walls and the new glass walls, which varies from 10 to 15 feet in width, is as essential a part of the architecture here as either of the two buildings. It is not a courtyard or an atrium but something else altogether: a kind of intermediate space that filters light, serves as a visual and psychological buffer, and makes everyone within the new building aware of the presence of the old one without feeling too tightly enclosed by it. The gap has been embellished with some tall, thin trees as well as planters and vines; and baskets of other plants hang within it, a further reminder that this is a real cubic volume, not something flat. The new glass building seems almost to float inside the old brick one; the two hover beside each other in shared space.

When the new building bursts out of the top into the big barrel vault, it yields a large, two-story, glass-roofed hall that Two Trees plans to use as an event space. The views in four directions are spectacular, but so is the space itself. It is a reminder that, often, the best way to add to a strong old building is not to lie down and play dead beside it, hoping that the new defers to the old so much that it disappears, but to respond to old strength with new strength, just as Foster did at Hearst. You can’t deny that some old buildings deserve to be treated as archeological restorations, but Domino wasn’t one of them. It’s a bold old building that now has a bold new building inside it.

Paul Goldberger, a Pulitzer Prize–winning architecture critic, is the author of several books, including Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry and Ballpark: Baseball in the American City