EDITOR’S NOTE:

An acquaintance of this publication’s, Professor Barnard Simmons, contacted us recently about an extraordinary discovery in his family’s archive: a trove of macabre stories written by his great-aunts in the 1930s, when they were little girls. “Perhaps you’ll find an excerpt fitting for Halloween?” he wrote. Indeed, we have. We’ll let Professor Simmons take it from here.

Preface

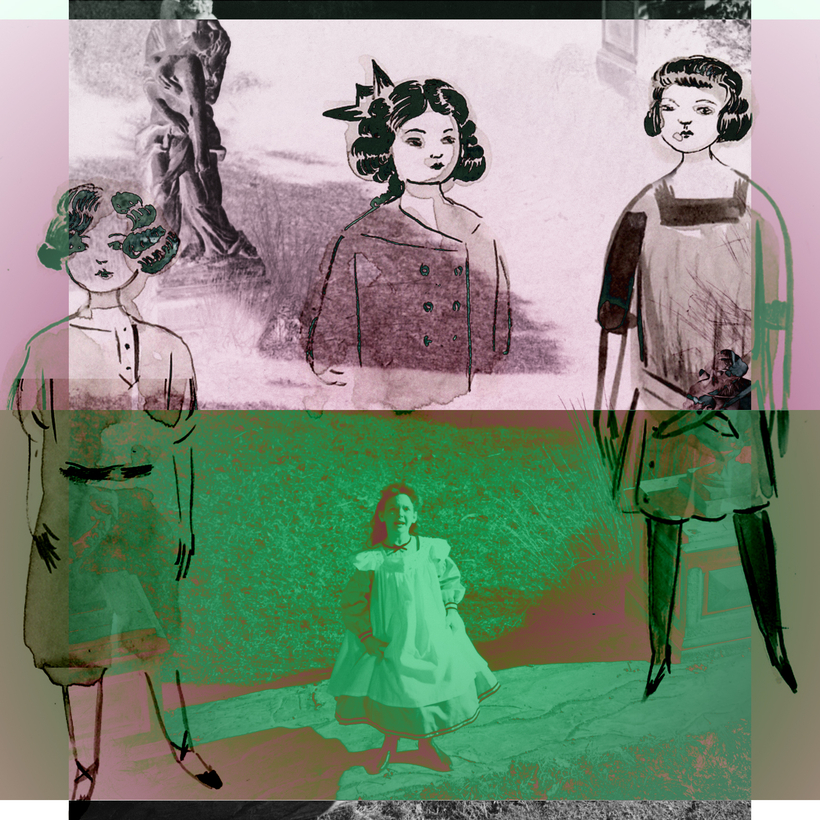

I am not the author of the remarkable story you are about to read. It is an artifact from my family’s distant past, written by my three great-aunts, the Simmons sisters: Emma, Eulalie, and Elizabeth, the last known as Libby. The three girls and their elder brother, my grandpa Andrew, grew up in the 1920s and 30s on their parents’ farm, in the western Massachusetts village of Frawley.