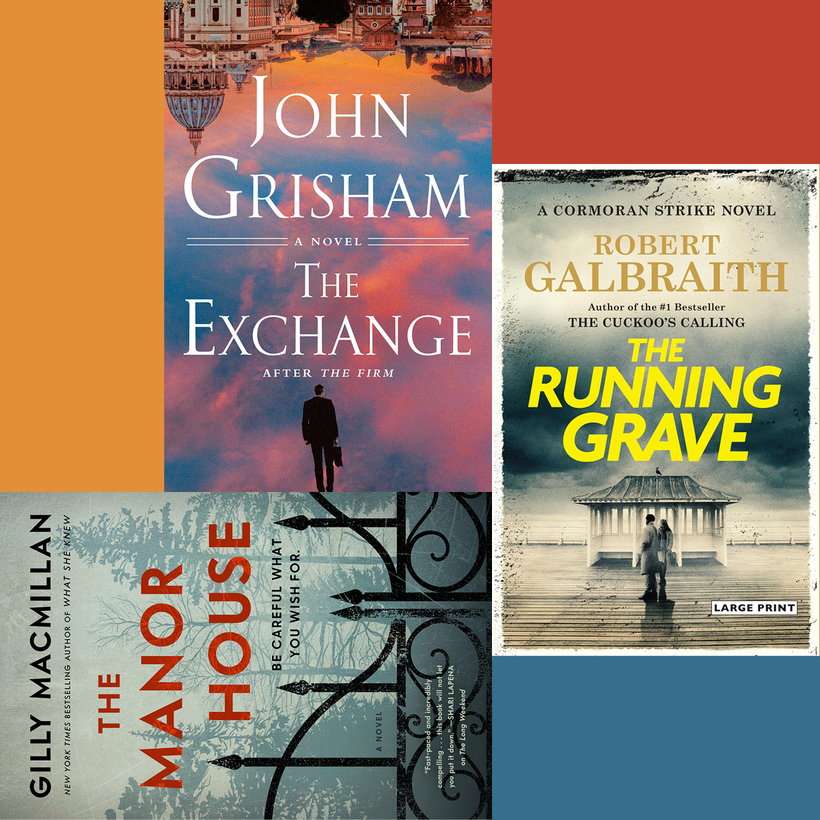

Consider this column a mystery trick-or-treat bag, replete with big books about such scary subjects as cults, international terrorism, and the dangers of winning the lottery. The bag needs a reinforced bottom to accommodate J. K. Rowling’s seventh Cormoran Strike novel, written under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith; in the past few years, installments of this series have expanded enough to make Karl Ove Knausgaard’s output look puny.

The Running Grave’s 945 pages may seem daunting, but fans will embrace this opportunity for complete, pleasurable immersion in the complicated and sometimes perilous lives and cases of private detective Cormoran Strike and his partner, Robin Ellacott. (Strike was an army intelligence officer who lost a leg in Afghanistan, then set up shop as a private investigator in London. Like many an old-school detective, he lives above his office, where he handles cases with Robin, who graduated from temp receptionist to partner.)