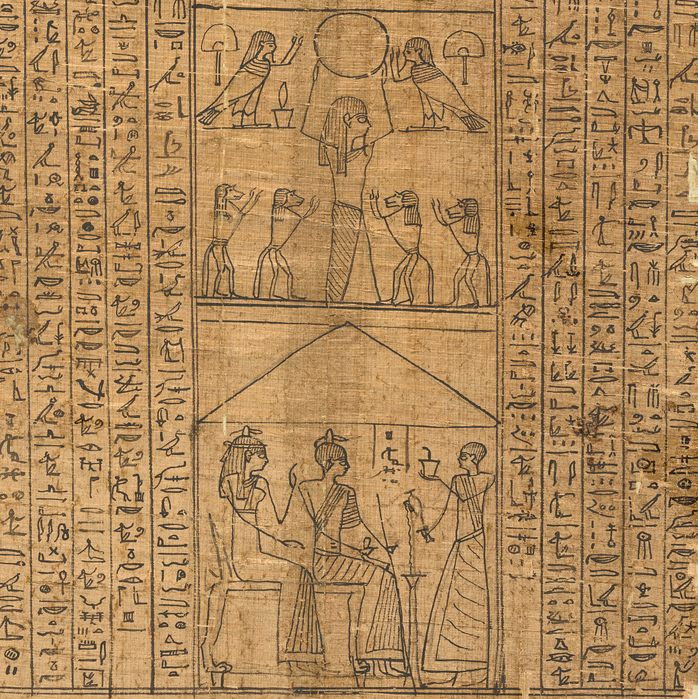

In the Book of the Dead—a manuscript custom-created for ancient Egyptians who could afford one—the crucial moment comes after the owner dies, when the gods weigh his or her heart against a feather. A pure heart will balance out. Awaiting the result is the hybrid monster Ammit, a lion in front, a hippo in back, her toothy crocodile jaws wide open. If the heart fails the test, Ammit will gobble it up, and instead of gaining eternal life, the owner’s spirit will vanish.

In the millennia-old papyrus that belonged to an Egyptian named Pasherashakhet, the feather test comes with a large ink drawing showing minor and major gods, the weighing scales, the heart, the monster, and Pasherashakhet himself. It’s one of the highlights of “The Egyptian Book of the Dead,” an exhibition that opens on November 1 at the Getty Villa, the antiquities-oriented campus of the museum, located in the low hills of California’s Pacific Palisades. In the Getty collection for four decades, the papyrus scrolls, inscribed mummy wrappings, and associated materials have never before been shown to the public. Until recently, the Getty itself had not delved deeply into this part of its collection, says the exhibition’s curator, Sara E. Cole. The Getty’s Roman, Greek, and Etruscan works are far better known.