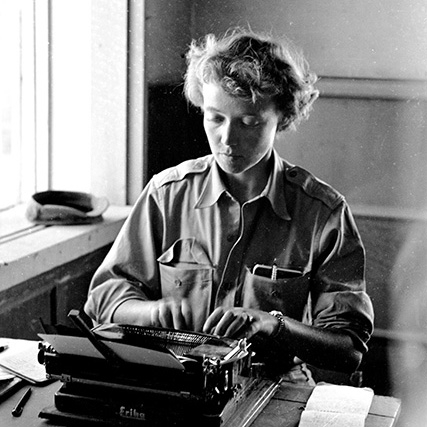

Ferociously competitive and disarmingly pretty, Marguerite Higgins was in her 20s when she covered the liberation of Dachau and the Berlin airlift. She would go on to become the first woman to receive a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for her front-line dispatches during the Korean War. Throughout her career, she alternately enchanted and enraged male colleagues in the newsroom and military, and inspired envy, gossip, and even a spiteful roman à clef. In a new biography, Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins, Jennet Conant uncovers the best and worst of an exceptional reporter who led a glamorous, swashbuckling life with its full share of mistakes, triumphs, broken hearts, and tragedy.

New York, 1943

The tabloids had a long tradition of employing glamour girls—the media magnate William Randolph Hearst believed that a little pulchritude could work wonders—and although it was a proven formula, it was not the Herald Tribune’s philosophy. Back then, there was a clear division between the respectable and the sensational press. A serious newspaper, it was thought, needed sober, sensible-looking reporters. Maggie did not fit the mold.