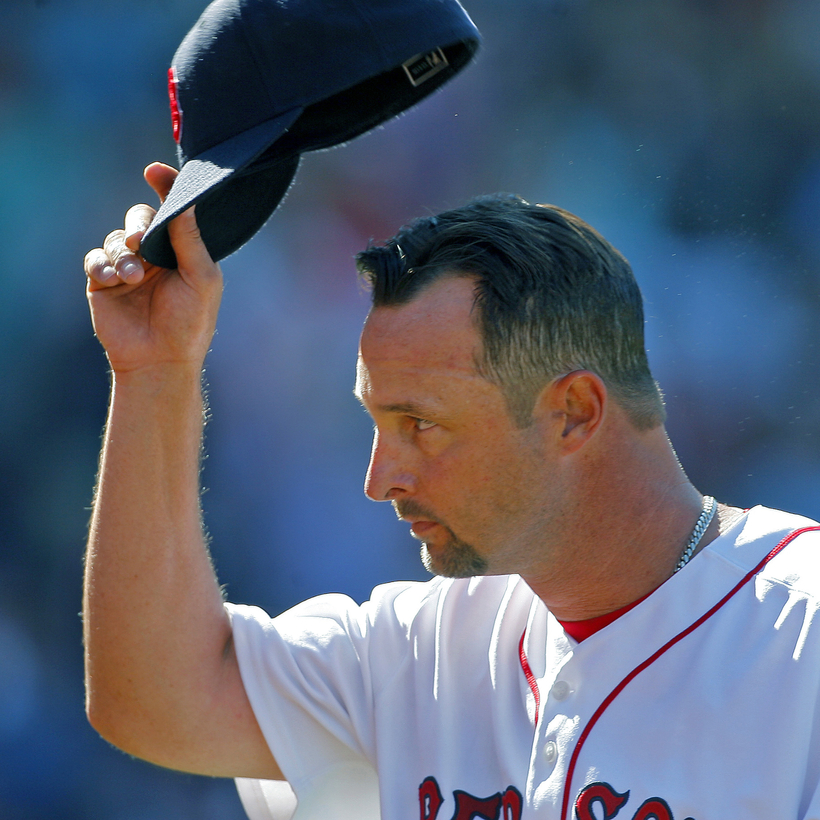

Baseball is a sport of romance. Fictionalizations aside, for its fans, the game continually inspires awe and surprise and wonder, and even in an era when its position as the American national pastime has been challenged, it remains oftentimes fantastical, perhaps allegorical, for those who still follow it. One feels compelled to characterize Tim Wakefield, the late Red Sox pitcher who died of brain cancer two weeks ago, at 57, as a foremost magician in the magical game.

Before Wakefield’s time, baseball lore told of mythical gods named Ted Williams, who could see the spin of the ball as it flew to the plate, and Babe Ruth, who pointed to center field at Wrigley just before he launched a 440-plus-foot home run directly over it. It spoke of the 12th inning of the sixth game of the 1975 World Series, when Carlton “Pudge” Fisk waved his home run to the right of Fenway Park’s left-field foul pole. Science says Fisk’s frantic flailing had no effect on the ball’s path of flight. But baseball lives solidly in the realm of absurdity. It would be foolish to think Pudge’s gesticulations had no effect, just as it would be fruitless to question the veracity of Williams’s acute vision.