Charm in the secret world is placed very high on the list of desirable qualities. It’s called, in recruitment terms, ‘entertainment value.’ And at its baldest, it means that your wretched little agent, stuck somewhere, is going to look forward to seeing you. He or she is run-down, exhausted, lying to her employers, and she wants to be turned into a goddess for the evening, and she wants to be listened to—she wants a confessor. In other words, the very attributes which in my father I tended to perceive as larcenous were the ones which my employers found attractive in me. So I’ve got it in for charm. Charm’s on my hit list.

—John le Carré

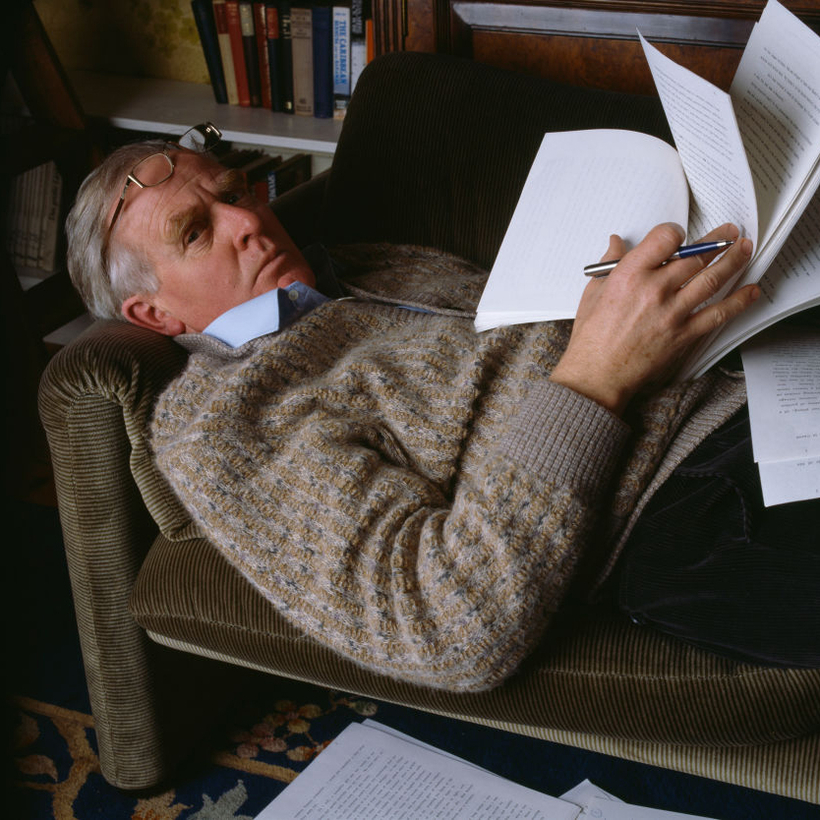

“Paper’s back,” David Cornwell told Steve Kroft in a 2017 segment on 60 Minutes. Paper was never not back for Cornwell, better known by his pen name, John le Carré. Once le Carré completed his celebrated, if brief, service with British intelligence, paper became an essential part of his arsenal. And he deployed it with precision for several decades, taking notes and writing longhand, eventually becoming one of the greatest and most popular writers of the 20th century.