The water taxi idled up to the fabled Hotel Excelsior on the Lido in Venice for my rendezvous with Contessa Marina Cicogna. As good a first line to a roman à clef as any. Inside, an unsympathetic renovation was thrown into stark relief by photographs evoking the romance and swagger of the hotel’s storied past, when Pierpont Morgan declared that “those who have visited Europe talk more of the Excelsior Palace than they do of the Doge’s.”

We were due to meet in the Blue Bar, which on a hot and sunny day in July was deserted. Outside, the Adriatic glittered. A bartender who looked barely old enough to drink was my only companion.

The granddaughter of Count Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata, one of the wealthiest and most influential men in Italy, Cicogna was born with a “golden spoon” in her mouth, which proved no impediment to a convention-defying life and career. While studying in New York, she met the daughter of movie mogul Jack Warner, who invited her to Hollywood, where she began taking photographs of, among others, Marilyn Monroe and Greta Garbo. Decades later, that hobby would lead to two books and several exhibitions, and to her accidental status as a chronicler of the jet-set world, long vanished.

Cicogna entered films in 1966 as a distributor, and the following year had three movies in the Venice Film Festival (her grandfather founded the festival at the Hotel Excelsior in 1932), including Belle de Jour, which she co-produced and which won the Golden Lion that year. She celebrated her win by throwing a party, sending “little Learjets” for Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, who were filming Boom! in Sardinia, and Jane Fonda and Roger Vadim, who were shooting Barbarella in Rome. She went on to produce Once upon a Time in the West (1968) and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, which won a best-foreign-film Oscar in 1971. “I was the youngest and certainly the only female producer at that time,” she said.

Along the way, there were rumors of affairs with Warren Beatty, Alain Delon, and George Hamilton, and lasting friendships with Franco Zeffirelli, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Vittorio De Sica as well as Audrey Hepburn and Jeanne Moreau. But it was Florinda Bolkan, the ravishing Brazilian actress, who became her partner for more than 20 years. After that relationship ended, Cicogna met a younger woman from Modena named Benedetta Gardona; the two have been together ever since. Cicogna ultimately adopted her in order to secure her future.

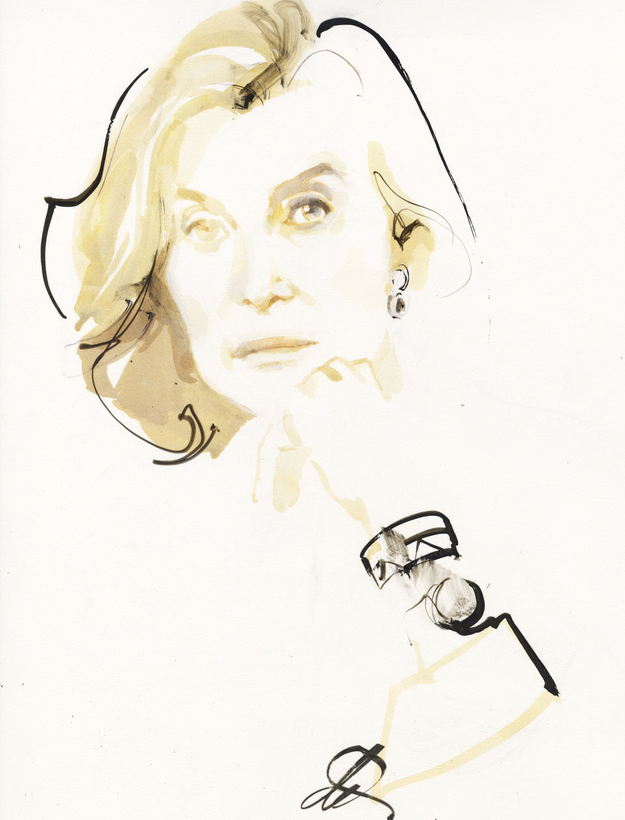

Cicogna walked into the empty bar. Ramrod-straight, white shirt, black pants, gold jewelry, hair a magisterial swoop. Stylish and intimidating. We adjourned to a corner, and I opened my sketchbook. “Are you drawing me?” Her gaze was intense, her brow arched. I was.

“Oh, I thought it was an interview. Good, I don’t really see the point of interviews.” She visibly warmed. I couldn’t resist asking about Rome in the 1970s, the decade of Jackie O’ (the nightclub, though, naturally, Cicogna knew the real Jackie O, and Aristotle Onassis and Maria Callas) and a second coming of la dolce vita. “I practically invented Helmut Berger,” she said of one of the era’s leading protagonists, and she regaled me with an anecdote about a shopping trip with Berger and his lover and mentor, Luchino Visconti. Berger was being petulant, trying things on and discarding them. The sales assistant caught Visconti’s eye, shook his head, and muttered, “Children.”

Berger didn’t like the familial implication and snapped, “Father? He’s not my father. He’s an old Italian queen.” Cicogna laughed at the memory. Later in life, she conceded, Berger “went bananas.”

Cicogna became easy company. She was interested that I had come from the Valentino show in Rome. Valentino Garavani, the label’s founder, is another long-standing friend. She currently favors Gucci. I asked her which one of all the fabled beauties could best electrify a room. “Jacqueline de Ribes and Florinda Bolkan,” she said, after contemplating the question.

The contessa was on a schedule, and after an hour or so, our time was up. As we left, she pointed to a photograph on the Blue Bar’s wall. It showed her outside one of the Excelsior’s striped cabanas with the great Italian actor Alberto Sordi. The date was 1953. Then she escorted me briskly to the front desk and arranged for me to take the hotel’s shuttle back into Venice. It was about to leave. “Run!” she said. I ran.

David Downton is an Editor at Large for Air Mail