Until the end, Piet Mondrian could be relied on to appreciate the work of a kindred spirit.

In 1943, a year before the Dutch artist’s death, at the age of 71, he was invited by Peggy Guggenheim to consider the submissions of several young artists for a new show in New York. Among the offerings was Jackson Pollock’s 1942 painting Stenographic Figure, which Guggenheim dismissed as having “absolutely no discipline at all.” But Mondrian felt differently. “I think this is the most interesting work I’ve seen so far in America,” he said. “You must watch this man.”

Guggenheim demurred, but a little while later, when the other jurors arrived, she marched them over to the Pollock and declared, “Look what an exciting new thing we have here!”

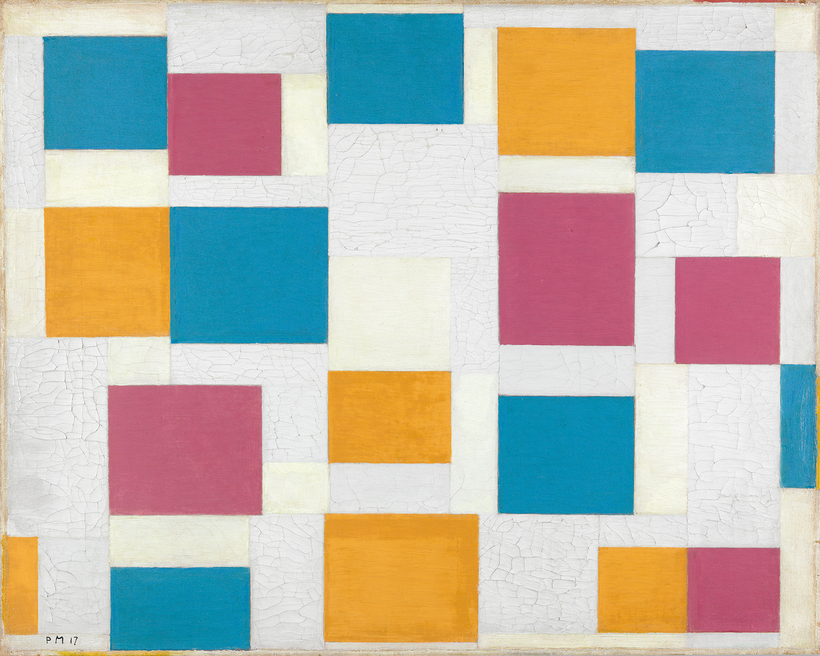

The shock of the new was Mondrian’s stock-in-trade. For most of his career he had to face down the sneers of traditionalist critics, one of whom described his abstract grid paintings as “just like tea towels.” This aversion for his work’s modernism reached a head in 1937 when two of his paintings were included in the Nazis’ “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) exhibition, in Munich. Fearing possible repercussions, especially for the articles he had written about the power of art to confront totalitarian tendencies, Mondrian left Paris, where he had been living, for New York via London.

Hans Janssen, the former chief curator of The Hague’s Kunstmuseum, which has the largest collection of Mondrians in the world, paints a particularly vivid portrait of these hazardous peripeties in Piet Mondrian: A Life. But most of all, Janssen’s book, which is the first comprehensive biography of Mondrian to be published in English, is a fascinating study of an artist so obsessed with his life’s work that he would let nothing and no one get in its way.

This was at its starkest in 1912, when Mondrian, who had just turned 40, left Amsterdam to live in Paris, where he was determined to discover the Cubist secrets of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque firsthand. “He did not hesitate,” Janssen writes. “He gave notice on his rented accommodation, broke off his engagement, sold as many paintings as possible, took the remainder to friends for safekeeping, and had his name removed from Amsterdam’s population register.”

At first glance, Mondrian’s shift from painting traditional Dutch landscapes to inventing works of geometric abstraction appears to be one of the most radical re-inventions in art history. But Janssen argues that it was a gradual transition, which involved Mondrian “turning the whole landscape tradition inside out, step by step, until he finally hit upon what became his abstract art.”

The work of other painters did not inspire Mondrian so much as the modern world itself. His passion for live jazz, dancing in nightclubs, and urban architecture nourished his imagination for what modernity should look like. Janssen makes no secret of the fact that he sometimes resorts to fiction—always derived from Mondrian’s own writings, letters, and articles—as a way of creating revealing dialogue.

In one such exchange, Mondrian tells his good friend the Dutch composer Jakob van Domselaer that “the visual expression of the big city, with all the life on the boulevards and in the cafés and dance halls, comes close to the visual expression that I search for in my work.” Gradually Mondrian came to believe that the apotheosis of this modern world would be found nowhere if not in America.

Mondrian had grown up in Winterswijk, a province of Utrecht in the Netherlands, stifled by a strict Protestant upbringing. He learned to paint what he saw: a landscape of trees, barns, windmills, and lakes. For 20 years he mastered this rather stolid art before painting one of his most gorgeous works, Avond (Evening): The Red Tree (1908–10), with its fanning branches and striking palette of red, blue, and yellow.

Janssen describes the tree “as not an element of a real world, but as an autonomous motif: a symbol, almost, of a world that he had conjured up.” The tree had set Mondrian on a journey toward abstraction that there was no turning back from.

Janssen communicates each stage in that journey, which ends with Mondrian in New York slaving over his final masterpiece, the unfinished Victory Boogie-Woogie (1944), with the verve of a true believer.

Tobias Grey is a Gloucestershire, U.K.–based writer and critic, focused on art, film, and books