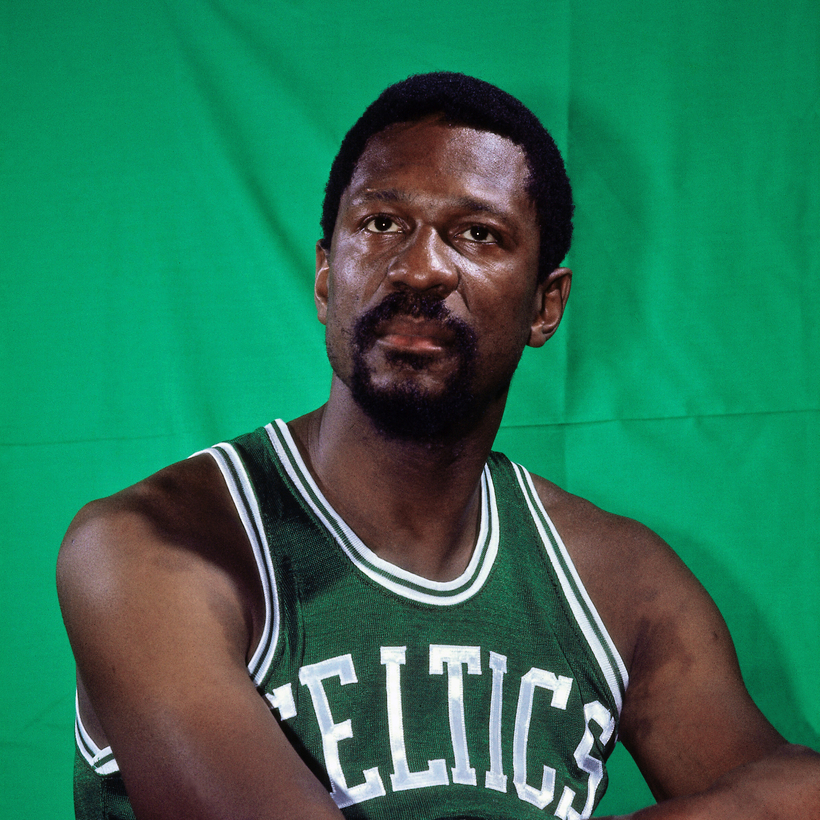

You don’t want to get lost in the statistics, but you do need to know that William Felton Russell won 11 N.B.A. championships with the Boston Celtics in 13 seasons (1957, 1959–66, 1968, 1969) and that as a player-coach from 1966 to 1969, he won N.B.A. titles in 1968 and 1969. Those are astonishing stats, important. But our sports are also about character.

“Sportsmanship” can be a naïve word, especially in the shadow of the failure and shame of the N.F.L.’s inept handling of Cleveland Browns quarterback Deshaun Watson’s numerous sexual-misconduct allegations and Trump’s infestation of golf. But if we are who we say we are as a people, if we believe in courage and integrity and fair play, then we define ourselves in our sports. New ways of thinking about race, about media, about celebrity have always played out on our fields and courts. That is the lesson of Bill Russell, who died Sunday at 88.

Bill was a transforming force. Tony Kornheiser said it best: “Russell represented a new type of Black athlete: the educated, outspoken, defiant star seeking nothing, expecting respect just for who he was.”

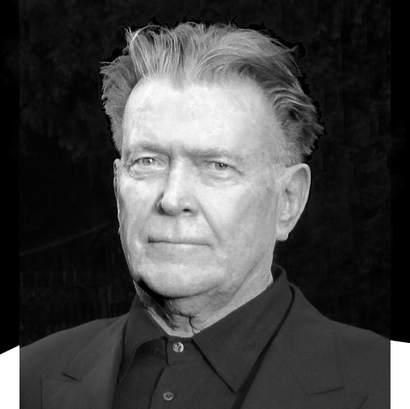

The thing about that quote is that Tony wrote it long before he became the star sportswriter of The Washington Post and the hair-trigger co-host of ESPN’s Pardon the Interruption. Those were his words in a blind letter to the editor in Sports Illustrated when he was just entering high school on Long Island.

I know how he felt. When I was 10, in the Santa Clara Valley, in California, I followed Bill Russell’s leading the improbable University of San Francisco Dons to back-to-back N.C.A.A. championships (1955 and 1956), including 55 straight wins and a single loss over two seasons. But again, it wasn’t about the stats.

When Tony wrote his letter to Sports Illustrated, Bill was playing in Boston Garden, where, early on, fans had yelled: “Go back to Africa,” “Baboon,” “Coon,” “Nigger.” Bill used all the hate that came at him to build his own character, and a ferocious game. You were not going to beat Bill Russell on the boards. Or anywhere else. In 1961, Bill famously boycotted an exhibition game in Lexington, Kentucky, when two of his teammates were refused service in a hotel coffee shop.

When the Celtics wondered how to increase attendance, more than half the fans polled answered, “Have fewer Black guys on the team.” There were still only about 15 Black men playing in the N.B.A. Bill called out the quota system. And screw the fans—Bill played for his teammates, and for himself, and turned the Celtics into a civic metaphor that the traditionally racist Boston fans did not deserve. By the time he stepped away from the Celtics, in 1969, he had changed the game forever.

Bill made basketball a vertical game. His spring and quickness and shot blocking intimidated and set the prototype for big men such as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Kevin Garnett. His rebounding and outpassing triggered a fast break that opened the game and pushed scores higher. Bill Russell ran, and he ran the Celtics. His head game was unmatched. He was uncanny with what he called his “Sleepy Dragon” look. Sometimes he glowered; sometimes he seemed to be laughing to himself. His Celtics coach, Red Auerbach, called him “the single most devastating force in the history of the game.”

Bill came out of retirement twice: to become coach and general manager of the Seattle SuperSonics (1973–77), building a team that would win the championship two years after he left; and for a brief, unhappy run with the Sacramento Kings (1987–88). That was it, but when I met him, 15 years later, that devastating force was still right there in your face. He was 68.

I had just taken a job at Sports Illustrated, which years before had given Bill its highest honor, Sportsman of the Year (1968), and then topped it with Greatest Team Player of All Time (1999). Bill was proud of those awards and was loyal to the magazine, particularly to Frank Deford, who had covered him with sharp insight: “The finest team player ever is by nature a loner who, by his own lights, achieved such group success because of his abject selfishness. You will never begin to understand Bill Russell until you appreciate that he is, at once, consistent and contradictory.”

Bill was invited to all the big Sports Illustrated events, and we were at the same table or sat together in the front row for access to the podium. At one such event, Bill told me about driving with his father as a boy in their army-surplus truck from Oakland to pick fruit somewhere in the Santa Clara Valley, where he knew I was from. I told him I picked cherries and apricots just like the Mexicans. Bill said they picked for little money, just like the Mexicans, too, except they always found a way to bring some extra fruit back to Oakland to sell or give to neighbors. I told him I liked the ‘cots best and he shook his head in disappointment.

“Cherries,” Bill said.

From then on, whenever I introduced him, I mentioned the cherries and apricots we had both picked, as if that tenuous connection somehow gave me more credibility to talk about Bill’s many stands as a Black man. But he and I never talked about any of that. When I would thank him for coming to a Sports Illustrated event, he would smile and maybe laugh, and say, “It’s my job.”

That laugh was distinctive, starting with a kind of sharp, surprisingly high bark, and then rolling out infectiously. Sports Illustrated was always grateful for Bill’s attendance and paid him significant honorariums, as is common in big-time sports. Once, hoping to amuse him, I recounted a marketing meeting where one of Sports Illustrated’s event coordinators said that Bill’s “brand” was a nice complement to Sports Illustrated’s. I don’t know what I was expecting—maybe a laugh and one of Bill’s zingers. He didn’t smile.

“Other way around,” he said with a chill, maybe pissed. But then a slight smile crossed his face, and he told me it was sad I did not know cherries were very much better than apricots.

After Sports Illustrated, I followed Bill from afar, and he seemed to be mellowing, happily going to important games, handing out trophies, and spending time mentoring young N.B.A. stars such as Kobe Bryant. Like everyone else who follows the N.B.A., I was moved, but then not surprised, when Bill attended the first Lakers-Celtics game after Kobe and his daughter Gianna died in a helicopter crash on the way to one of her games. Bill showed up at the Staples Center wearing a No. 7 Lakers jersey, Kobe’s jersey. There he was, transcendent again.

I thought of Bill when George Floyd was murdered. I wondered where he had watched that white Minneapolis policeman calmly choke out a Black life. Bill wrote in Slam magazine that the murder was “yet another life stolen by a country broken by prejudice and bigotry,” and that it brought back all the abuse he had endured when none of his honors or championships could shield his family from white supremacy. It was a tough piece to read: “Bigots broke into the house, spray-painted ‘Nigga’ on the walls, shit in our bed. Police cars followed me often.... I marched in Washington, supported Ali. After that, the death threats started coming.” I read it again. Shit in our bed.

Bill ended the piece with a reference to the song “Strange Fruit” and said history must not repeat itself: “In many ways, I owe my happiness to the love my parents gave me. Their love gave me the confidence to simply be me: a proud Black man, fair, and I believe, dignified. Of course, as too many Black and Brown mothers will tell you, all the love in the world can’t keep a Black child from being murdered.”

That had to change, and it had to change now. And that was Bill Russell, who had done more to end racism in sports than any athlete since Jackie Robinson, still doing his job.

To hear Terry McDonell reveal more about his story, listen to him on AIR MAIL’s Morning Meeting podcast

Terry McDonell was the editor of Sports Illustrated from 2002 to 2012