The masterpieces of still-life painting leap readily to mind. Those “banquet pieces” from the Dutch Golden Age depicting lavish spreads of crusty bread, cheese, enticing mounds of grapes, tipped-over goblets, and gutted candles. Caravaggio’s basket of fruit. Manet’s bunch of asparagus. Cézanne’s apples. A veritable Olive Garden of delights.

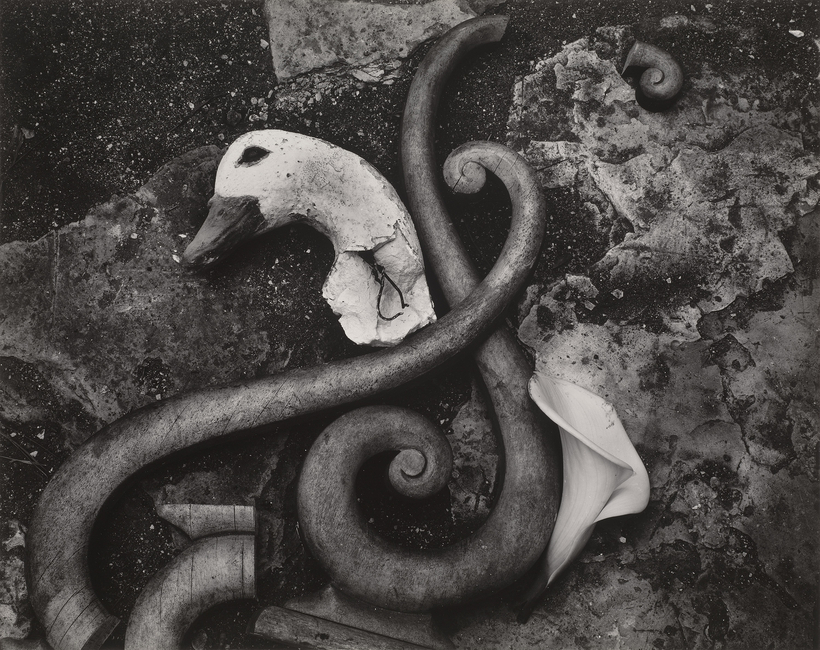

With the invention of photography, the flick of the painter’s brush was joined by the click of the camera, and still-life photography was born, extending and advancing the art of inanimate portraiture. Since the early 20th century, when soft-focus treatments of water vases and drooping petals from pioneers such as Baron Adolph de Meyer beatified the commonplace, still-life photography has accumulated its own abundant array of tabletop treasures and everyday objects that appear to emanate an eerie afterlife of their own.