translated by Antony Shugaar

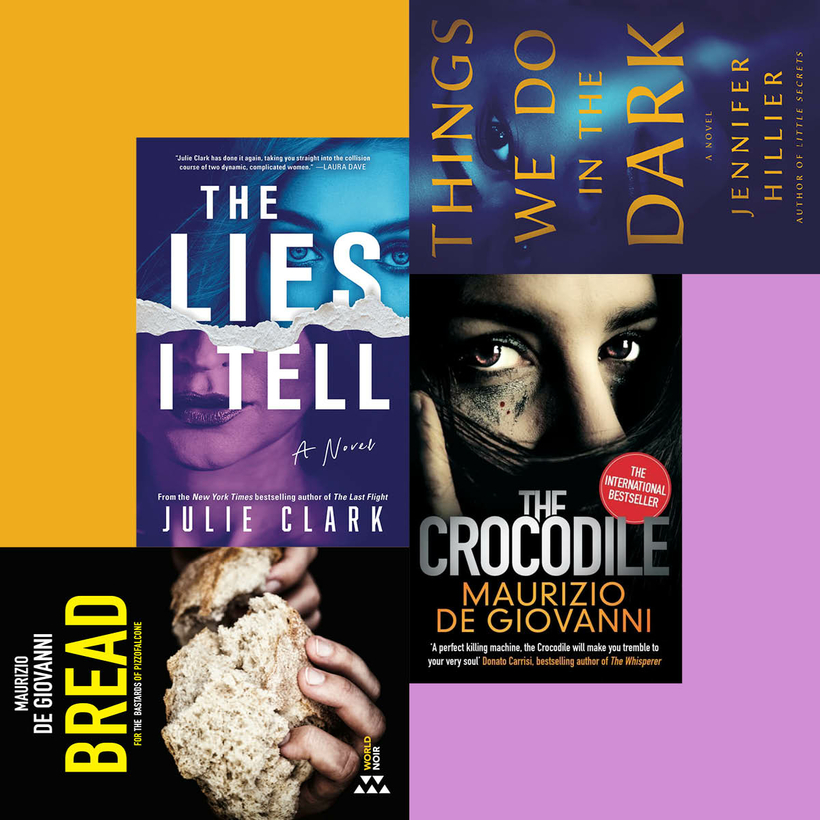

As Ghislaine Maxwell’s lawyers poured out the unpleasant details of her poor-little-rich-girl upbringing in hopes of getting a lighter sentence for abetting Jeffrey Epstein’s crimes, it’s interesting to consider, for perspective, the women in Jennifer Hillier’s Things We Do in the Dark and Julie Clark’s The Lies I Tell. Their childhoods were far worse: Joelle Reyes suffered horrific physical abuse by her mother, and Meg Williams ended up living out of her car.

They’ve broken the law, too, but only to survive; a judge would have to be made of stone not to take pity on them. At least Maxwell grew up in mansions and had a yacht named after her, which certainly doesn’t excuse her bad daddy but must have helped ease the pain just a bit.