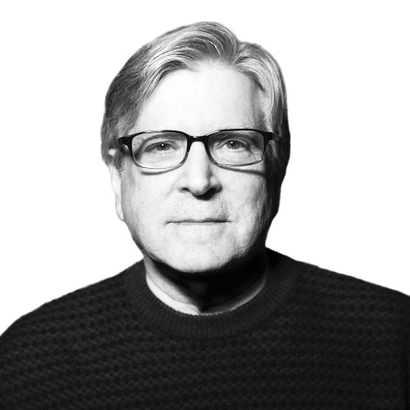

Ron Shelton hears America singing, schmoozing, and swearing. His writing-directing debut, Bull Durham (1988), transported fans into the offbeat mystique and comic muck of baseball. As Shelton’s spellbinding heroine Annie Savoy, played by Susan Sarandon, reminds us, Walt Whitman called the sport “our game … America’s game.” Shelton’s new memoir, The Church of Baseball, does for filmmaking what Bull Durham did for the national pastime: it demystifies the craft, pillories the business, and celebrates the calling with wit and passion.

Shelton’s prose is as natural as his dialogue, and he conjures characters with casual mastery: Kevin Costner’s gung-ho professionalism (he insisted on auditioning as an athlete), Tim Robbins’s freshness and immediacy (“his boyish face, his physicality, an impish grin”), and Sarandon’s sui generis razzle-dazzle (“Susan flashed into the room looking brilliant,” wearing “a tube dress with four-inch red and white horizontal stripes that announced her presence with authority”).