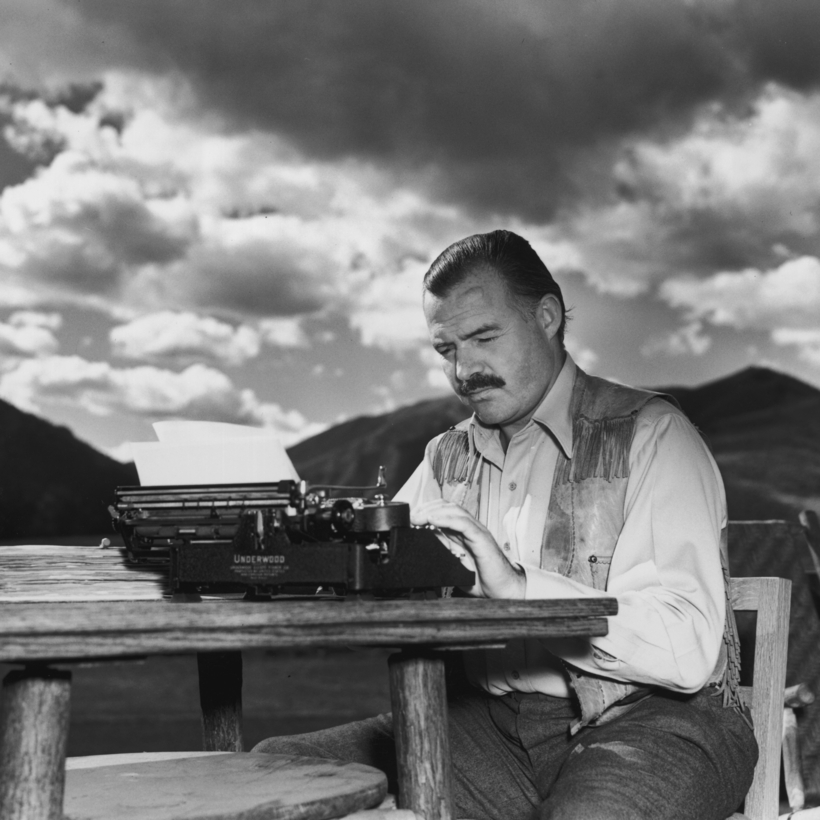

“All you have to do is write one true sentence,” declared Ernest Hemingway in his posthumous memoir A Moveable Feast. The remark has echoed across the years following his death, in 1961, despite Hemingway’s own fall from popular adulation during that same period.

Enter two latter-day projects bent on revitalizing the late artist’s significance.

One was Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s three-part PBS documentary, Hemingway, which was met with both praise and criticism when it was released, last year.

The second is One True Sentence, a plummy anthology of interviews conducted by Hemingway scholars Mark Cirino and Michael Von Cannon—the host and producer, respectively, of One True Podcast, from which these talks were transcribed. Introduced by Burns and Novick, the book is bright, intense, and fascinating: a kind of charm bracelet of brief conversations with people either connected to Hemingway, or who themselves figure on the American cultural radar.

Each interviewee was given the same prompt: Which sentence, of the thousands comprising Hemingway’s towering oeuvre, stands as that fabled “true” one, and why?

Some answers:

“Then the fish came alive, with his death in him, and rose high out of the water showing all his great length and width and all his power and his beauty.” (The Old Man and the Sea)

“The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.” (For Whom the Bell Tolls)

“He would lie in the bed and finally, with daylight, he would go to sleep.” (“A Clean, Well-Lighted Place, from the collection Winner Take Nothing)

“In the early morning on the lake sitting in the stern of the boat with his father rowing, he felt quite sure that he would never die.” (“Indian Camp,” from the collection In Our Time)

Among the contributors are authors, relatives, and actors. Stacy Keach, who played Hemingway in a 1988 television mini-series and narrated the complete short stories for an audiobook edition, first read Hemingway in college and was instantly galvanized: “He was talking to my soul.” Adrian Sparks, who starred in the one-man play Papa and the film Papa: Hemingway in Cuba, so keenly resembled the late icon that Cubans ran up to him during that filming, weeping.

Valerie Hemingway, who was married to Ernest’s late son Gregory (who later became Gloria), wrote Running with the Bulls: My Years with the Hemingways. Mark Salter served as aide to and speechwriter for John McCain, who revered Hemingway and read passages aloud to his staff. From the literary world, meanwhile, are discussions by Brian Turner, Elizabeth Strout, Joshua Ferris, Andre Dubus III, Jennifer Haigh, Russell Banks, and Pam Houston.

In an interview with Von Cannon, Cirino notes: “[p]ared down style is not always the best illustration of [him]. Everybody has their own Hemingway.” Burns echoes that thought, warning in his introduction against “the superficial, conventional wisdom.”

In his interview, the writer and photographer Michael Katakis extols “the implying of terrible, terrible things wrapped in such beautiful, beautiful language.” In another, the journalist and author Craig McDonald notes, “As a fiction writer, [Hemingway’s] a sublime poet. As a poet, he’s a terrible poet.”

Then there’s university professor and editor of The Hemingway Review, Suzanne del Gizzo: “Those sentences are earned.... It’s really funny when people try to make fun of Hemingway because you think, ‘On how many levels do you not get it?’”

Joan Frank is the author of several books, including the novel The Outlook for Earthlings. Her new essay collection, Late Work: A Literary Autobiography of Love, Loss, and What I Was Reading, will be published in October