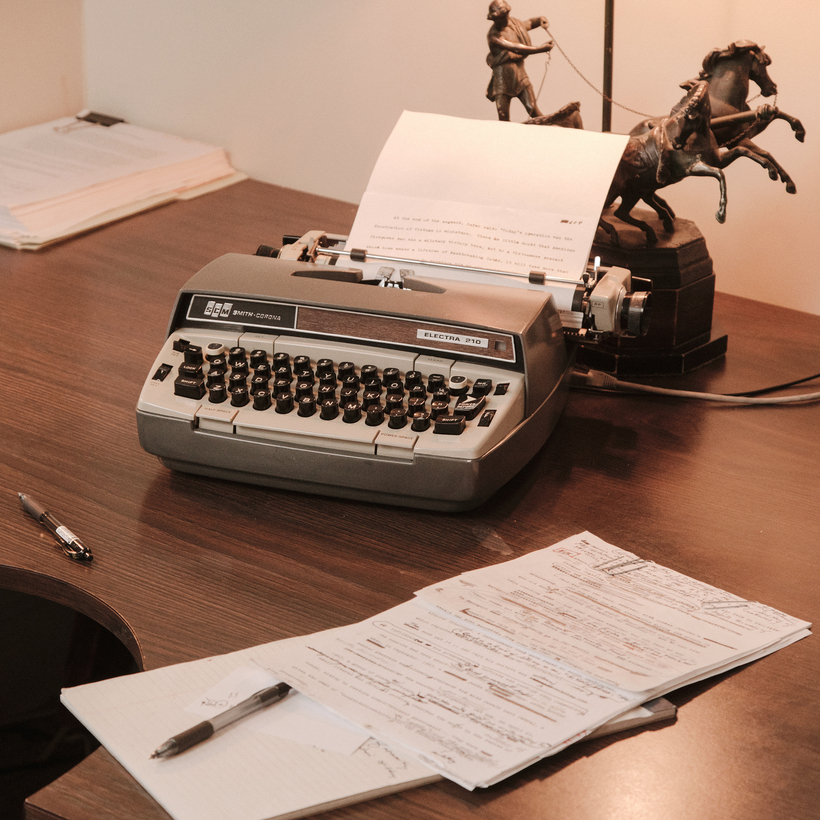

Turn Every Page: The Adventures of Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb, a new documentary that I saw at its premiere on Sunday at the Tribeca Film Festival, contains a multitude of love stories encased in a story of suspense.

One might assume, given the movie’s subtitle, that the principal love story is between Robert Caro, the author of five monumental works of political history, and his editor, Robert Gottlieb. But that is not the case.