When I was at university, I used to imagine that one day the other immature teenagers around me would become famous. It sort of happened. Admittedly, the people I was actually close to at Oxford University from 1988 to 1992 didn’t get there. They now live in provincial towns, with mortgages and problematic spouses.

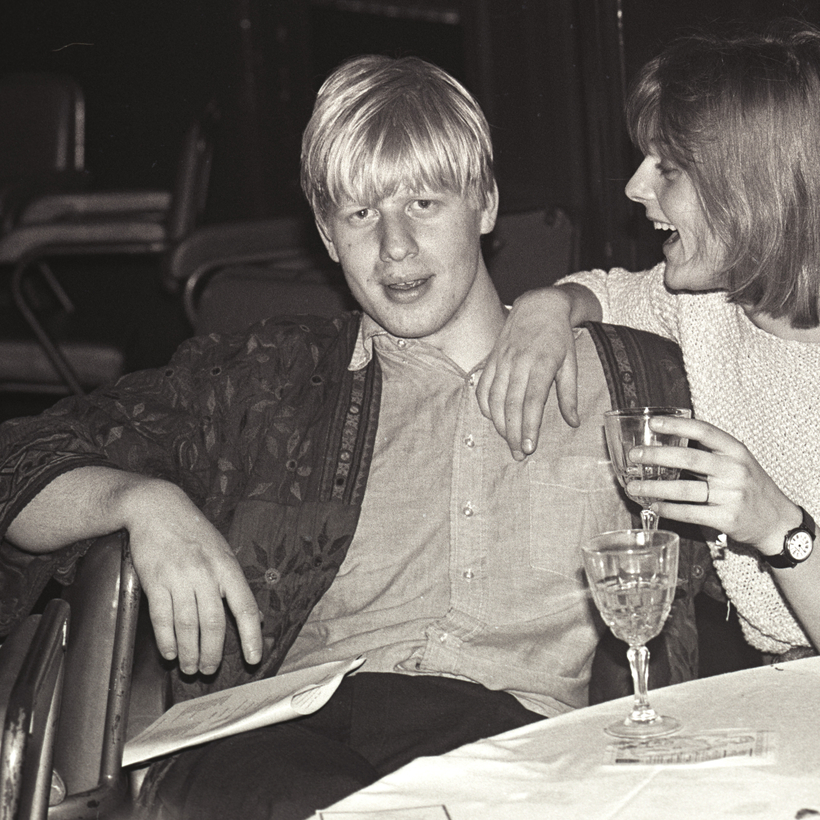

But a cohort of private-school-educated Conservative men who were at Oxford with me, or just before me, did go on to drag the U.K. out of the European Union and now run the country. Boris Johnson is prime minister, and Oxford contemporaries of mine such as Dan Hannan, Jacob Rees-Mogg, and Dominic Cummings have helped remake the U.K.