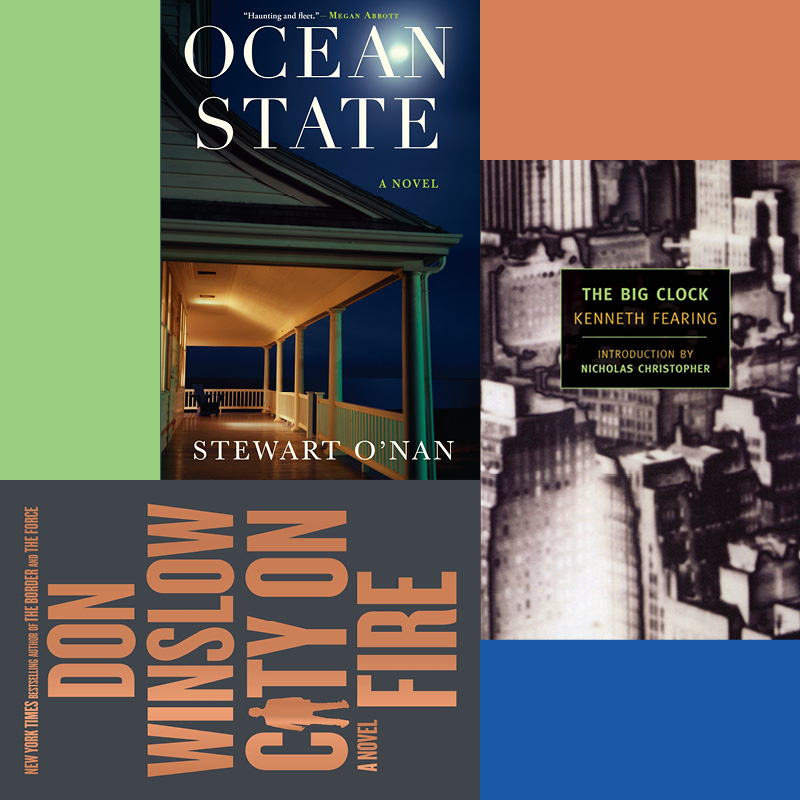

What is it about the beautiful women of crime fiction that makes them worth killing for? Three very different tragic beauties inspire violence ranging from explosive expressions of jealousy in Ocean State and The Big Clock to the collateral damage of Mob warfare in Don Winslow’s City on Fire.

In a foreword, Winslow explains that this is the first book in a planned trilogy inspired by the Iliad, but instead of Homer’s heroes of ancient Greece battling for Troy, he gives us Irish mobsters warring with their Italian counterparts in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1986. It’s a smart move away from familiar New York–New Jersey territory to a lesser city in the organized-crime hierarchy, vividly rendered by Winslow in all its scruffy glory.