Almost overnight an obscure former White House intern became one of the most famous women in America. When news of the President Clinton sex scandal broke in January 1998, picture editors scrambled to find images of Monica Lewinsky with the president.

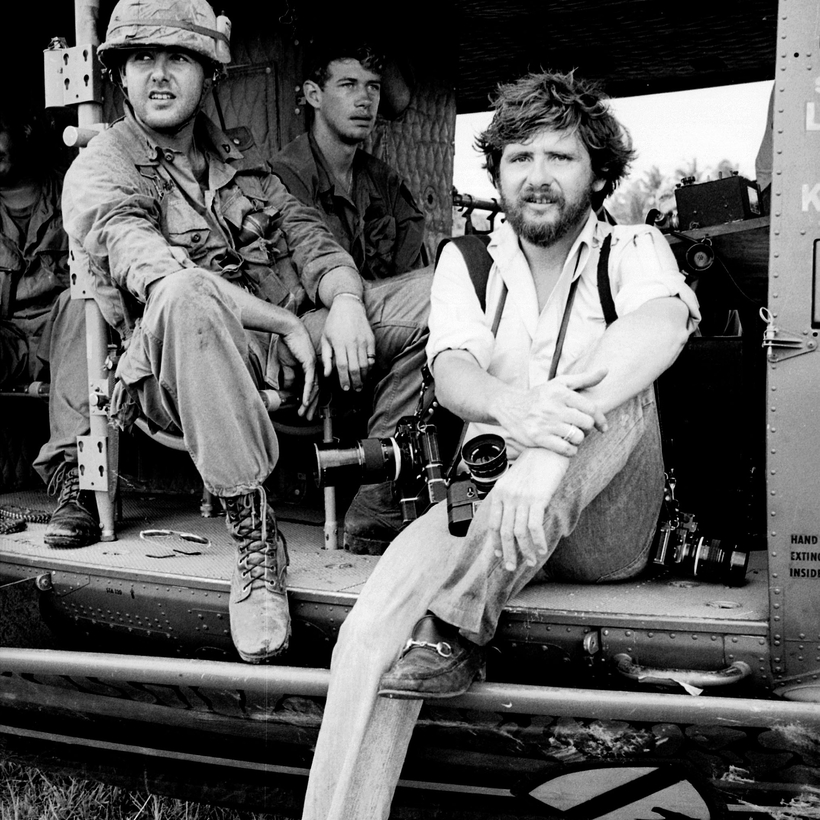

Dirck Halstead thought she looked vaguely familiar. One of the United States’ foremost photographers of war zones and political battles, Halstead made his reputation covering the Vietnam conflict and was a White House photographer for Time magazine from 1972 to 2001.