In an era when Ali Wong, Tiffany Haddish, Hannah Gadsby, and so many other women comics seem to dominate streaming TV, it’s hard to imagine a time when stand-up comedy was essentially a boys’ club.

In the latter years of vaudeville, in the Vegas and Borscht Belt showrooms of the 1940s and 1950s, and on most of the early TV variety shows, the joke tellers were almost exclusively men. As late as 1979, TV’s leading comedy kingmaker, Johnny Carson, confessed that women comics “sometimes are a little aggressive for my taste. I’ll take it from a guy, but from women, sometimes, it just doesn’t fit too well.”

Yet it was Carson, in February 1965, who gave a brassy 31-year-old Barnard graduate struggling to make it in New York nightclubs her big break. Sitting on the couch next to Carson, as the show’s last guest, Joan Rivers cracked up the Tonight Show host with rapid-fire jokes about her looks, her love life, her bad driving. The smash appearance supercharged her rise to become the best-known female stand-up in America—opening the doors for countless other women, who might reject Rivers’s self-deprecating rat-a-tat style but would acknowledge her as the key groundbreaker.

What’s novel and valuable about Shawn Levy’s new book, In on the Joke: The Original Queens of Stand-up Comedy, is that Joan Rivers is the end point, not the beginning. Levy (the author of books on Jerry Lewis, the Rat Pack, and the Chateau Marmont) wants to celebrate the women who came before her—the lonely pioneers who had almost no models to draw on, fought for attention in a male-dominated industry, and even today are not sufficiently appreciated.

One reason is that they often worked in fields largely off the radar of mainstream audiences and media. Jackie “Moms” Mabley, born in 1894 in the mountains of North Carolina, with more siblings and half-siblings than she could even count (and five children of her own before she was 23), developed a successful singing-and-comedy act on the so-called Chitlin’ Circuit of Black vaudeville houses and became a star attraction at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, only later breaking through to a broader audience with records and TV appearances in the 1960s.

Minnie Pearl was a fixture at Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry and one of the most popular country stars in America for decades, but little noticed by the cultural taste-makers on the East and West Coasts. Bawdy comedians such as Belle Barth and Rusty Warren pushed the boundaries of risqué sex humor in the disreputable venues of burlesque and underground “party records.”

What’s more, they typically had to hide behind exaggerated, unfeminine caricatures. “If they wanted to be funny,” says Levy, “they had to, in some way, deny their womanhood.” Mabley was in her early 40s when she wore a housecoat, a floppy hat, and slippers, and passed herself off as a salty, plainspoken grandma. (“Moms don’t know no jokes. But I can tell you some facts.”)

Sarah Ophelia Colley graduated from the best finishing school in Tennessee and worked as a director of traveling theatrical shows, before re-inventing herself as Minnie Pearl, a stereotypical country bumpkin, with her signature straw hat (a price tag dangling from it) and down-home greeting: “How-deeeee!”

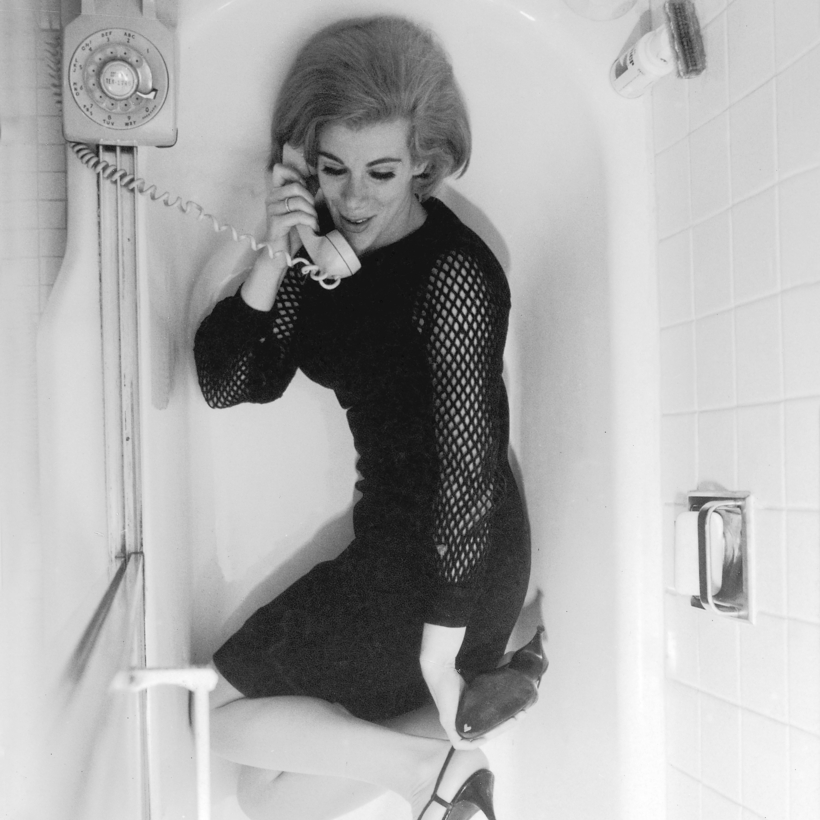

Exhibit A was Phyllis Diller. A housewife with five children and a bad marriage, she parlayed her copywriting and radio-marketing jobs into a few comedy gigs at small clubs in San Francisco’s hip North Beach. Her highbrow routines—parodies of Amahl and the Night Visitors and Yma Sumac—brought her some local notoriety.

But only when she replaced her business suits with garish, baggy outfits (to hide her well-proportioned figure) and began making fun of her looks, her ineptitude at housework, and her hapless husband, Fang, did she break through to national fame in movies and TV, becoming for many years the most popular female comedian in America.

Jean Carroll was the exception—virtually the only female stand-up of the era who didn’t have to demean herself to get laughs. She was a sophisticated, stylishly dressed adult, making jokes about marriage and family just the way the men did. “Now don’t tell me you’re going to be picking on your husband again,” teased Ed Sullivan before one appearance on his show. “Who do you want me to pick on,” she replied, “Alan King’s wife?” Yet Alan King was a TV staple for decades, while Carroll, despite her success in nightclubs and on TV, essentially dropped out of show business in the 1960s, and is today largely forgotten.

There are more: Totie Fields (exploiting another stereotype, the sex-crazed fat girl) and Elaine May, the outlier in this group, since she was primarily a sketch comic, but still a major force in the “new wave” of cerebral stand-up that emerged in the late 50s and early 60s. Levy profiles each in affectionate, well-judged, thoroughly researched detail.

Levy has done an admirable job of resurrecting a band of unique, unjustly neglected performers. Much of their comedy may seem retrogressive, politically incorrect, even demeaning today. But Ali Wong would be nowhere without them.

Richard Zoglin is the author of Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America