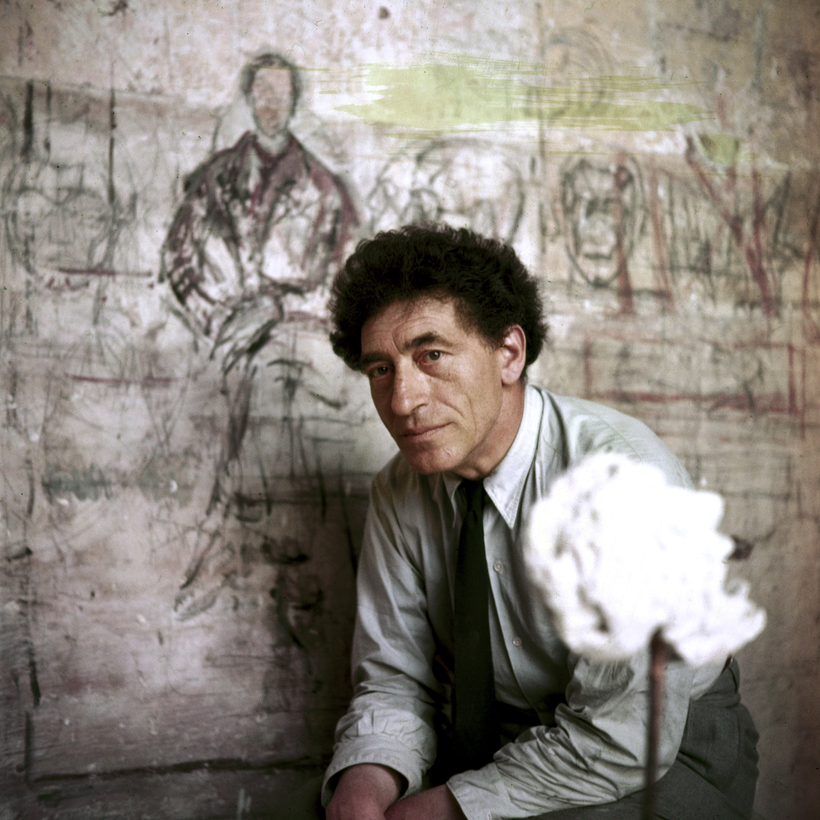

Alberto Giacometti (1901–66) stands outside modern art’s broad historical narrative of revolutionaries versus traditionalists. Where other members of the avant-garde were guided by their imaginations or emotions, Giacometti evolved an aesthetic rooted in close observation of the subject before him, thus declaring his allegiance to the past. At the same time, he explored the most forward-looking ideas about perception, representation, and what it meant to see and depict the world. This made him, uniquely, both reactionary and modern—a radical conservative.

Giacometti started out as a member of the Surrealist movement. Beginning in the early 1920s, he made semi-abstract sculptures that dealt with themes of sexual violence (Woman with Her Throat Cut) or dreamworlds (The Palace at 4 a.m.). By the mid-1930s, he had begun to feel that there was little difference between these fine-art objects and the vases and lamps he was designing for an interior decorator, commercial objects that helped pay the rent. Both were realizations of a preconceived image and thus, to him, somewhat arbitrary creations and pretty much interchangeable. Giacometti wanted his art to be grounded in lived experience.