It was as they returned from the April meeting of SHAP, the Société Historique et Archéologique du Périgord at which the mayor of St. Denis had been installed as the new president, that the mayor asked his chief of police for a special favor.

“You know that our Society was founded on May 27 in 1874,” he began as they drove from the meeting in Périgueux back to their own commune some 40 kilometers to the south.

“Given your skill as a cook, Bruno, do you think you could arrange an anniversary dinner for the society next month that would re-create the food of our Neanderthal or early modern forebears, but in a way that would appeal to the modern palate? And if it works, might you persuade Sylvain, that traiteur friend of yours, to prepare it for the members? He’s used to cooking for 40, 50 people.”

Bruno Courrèges, in the passenger seat of the mayor’s big Citroën, looked in surprise at the man who had hired him and had over the years become a friend and the nearest he’d ever known to a father. He had heard many unusual suggestions from the mayor over his 11 years as the town policeman, but this surprised even him.

“Here in the Périgord, the global center of prehistoric studies, with more than a hundred caves decorated with the art of our ancestors, such a feast would bring in publicity and tourism,” the mayor added.

It would also, Bruno thought, mark the mayor’s new tenure of SHAP in a striking and probably popular way that would certainly attract considerable publicity for the mayor, locally and, perhaps also, nationally. Moreover, the municipal elections were looming, and even though Bruno was convinced that the mayor would be re-elected so long as he lived, and quite probably thereafter, the mayor never took the voters for granted.

“It won’t be easy to get the right balance between historical authenticity and modern tastes,” Bruno said. “We could give them raw fish followed by charred meats with nuts and berries for dessert, but I don’t think that would go down very well. And what about wine?”

“Georgians were making wine in the Caucasus 8,000 years ago, and what about the pre-Roman wines at Château Belingard, right here in the Bergerac?” the mayor replied. “And we don’t want it too authentic. You might manage it, but I think most of us in St. Denis are a little old to be hunting aurochs and reindeer with stone axes and spears.”

Bruno smiled to himself at the thought but knew he’d better take this idea seriously. Still, the mayor was right; he recalled from a SHAP lecture that reindeer had been the mainstay of the prehistoric diet, along with occasional beef and horsemeat. And the earliest bone harpoons in the museum were more than 13,000 years old, so they could have fish on the menu.

“The problem will be some kind of sauce to go with the meat,” said the mayor.

“Venison would be the easiest with black-currant sauce,” Bruno replied.

“They’ll be expecting that,” the mayor objected. “We know Neanderthals and Cro-Magnon people alike ate aurochs, which are ancestors of our cattle, so let’s do something with beef, maybe a mushroom sauce? Mushrooms are old enough—the ancient Romans thought they were the food of the gods.”

They arrived in St. Denis agreeing that more research was needed. So that evening Bruno dropped round to see his friends Clothilde and Horst. Professional archaeologists who also lived in St. Denis, they had been married by the mayor with Bruno as a witness.

“Given your skill as a cook, Bruno, do you think you could arrange an anniversary dinner … that would re-create the food of our Neanderthal or early modern forebears?”

Clothilde, a small, energetic woman with red hair and flashing eyes, was the senior curator at the National Museum of Prehistory in the nearby town of Les Eyzies. She and Horst had enjoyed, or perhaps survived, an on-again, off-again passion for each other at digs across Europe and the Middle East until Horst had retired from his teaching post at the University of Cologne and persuaded her to marry him. He now ran the museum’s excavation program.

Their initial looks of surprise were mixed with amusement when Bruno described the mayor’s latest mission over a glass of kir. He knew he had come to the experts. The previous year, Clothilde had given a lecture on the very topic of prehistoric diets at the museum, and Horst had recently published an article in the popular magazine Archéologie on phytoliths, the fossilized particles of plant tissue that could be found in the middens, the rubbish dumps of prehistoric people.

“They had fire so we can argue that in principle they could have smoked their food, or dried it like the Native Americans with their pemmican,” said Clothilde, thoughtfully. “And there’s some new isotropic research on skeletons suggesting that fish formed up to a quarter of their diet.”

She smiled at Bruno and announced, in the solemn tones of a pompous maître d’hôtel: “Alors, mesdames, messieurs, the chef proposes some smoked trout with perhaps a little reindeer pemmican on the side to begin.”

“Remember the dig at Castel Merle where we found the basalt stones in a clay-lined pit that you thought might have been used to boil water?” Horst chimed in enthusiastically. “The associated pollen was nearly 30,000 years old.”

“How did that work?” Bruno asked, happy to see Horst and Clothilde getting into the spirit of the idea.

“Two ways,” said Clothilde. “Scoop out a hole in deep enough clay, light a fire so the clay dries, reline it to seal the cracks, and then line the base of the hole with basalt rock and light a new fire. Once it is down to embers put in your meat, well-wrapped in damp leaves, cover the hole with a large stone and Voilà, a baking oven. Or add water and then take red hot stones from the fire with a well-soaked piece of reindeer hide and drop them in to boil the meat, or at least warm it.”

“The people who erected the scaffolding at Lascaux so they could paint the ceilings used wood and rawhide,” said Horst. “So they would have easily been able to build a frame they could cover with skins to make a smoker, or another on which they could lay green shoots to barbecue their meat.

“And they were very good at fire technology. That’s why they were able to invent the only way to light those caves so they could see to paint deep underground. Rendered reindeer fat with juniper twigs for a wick gave them a smokeless light so the chalk walls were not darkened.”

“Right,” said Bruno. “They could have roast, boiled, and barbecued meat. And obviously they had nuts and berries, but what else did they eat? Your Archéologie article said you’d found evidence of seaweed being a regular food in coastal communities, Horst. But we’re more than a hundred kilometers from the sea here.”

“Well, they used kelp for food and also for cordage, baskets, and food wrappings, but kelp doesn’t preserve well,” Horst replied. “What we found were fossils of tiny gastropods that lived on kelp, and now we’ve found similar fossils here inland of gastropods that lived on duckweed in rivers, water lilies in ponds. Butomus umbellatus, or flowering rush, grows in moist soil or shallow ponds and the tubers are 50 percent starch, edible when cooked, although rather tasteless. The seeds are edible raw. And we’ve found those in middens here.”

“There’s new research from York and Cardiff Universities into the dental plaque from prehistoric human teeth that shows evidence of microscopic fossils of plant matter,” said Clothilde.

“Radishes and turnips are native to this region, even if they were thin and spindly things in those days. They could have eaten those. Sorrel is native here, and so are wild garlic and nettles, so you could make nettle soup. And you know there’s a new project to develop duckweed as food? People eat it in Southeast Asia, and it has as much protein as soya beans. I tried some once, and it was tasteless and stringy, not very appetizing, but it would keep you alive.”

“Perhaps with a vinaigrette and mixed with wild garlic leaves it could be a kind of salad,” suggested Bruno.

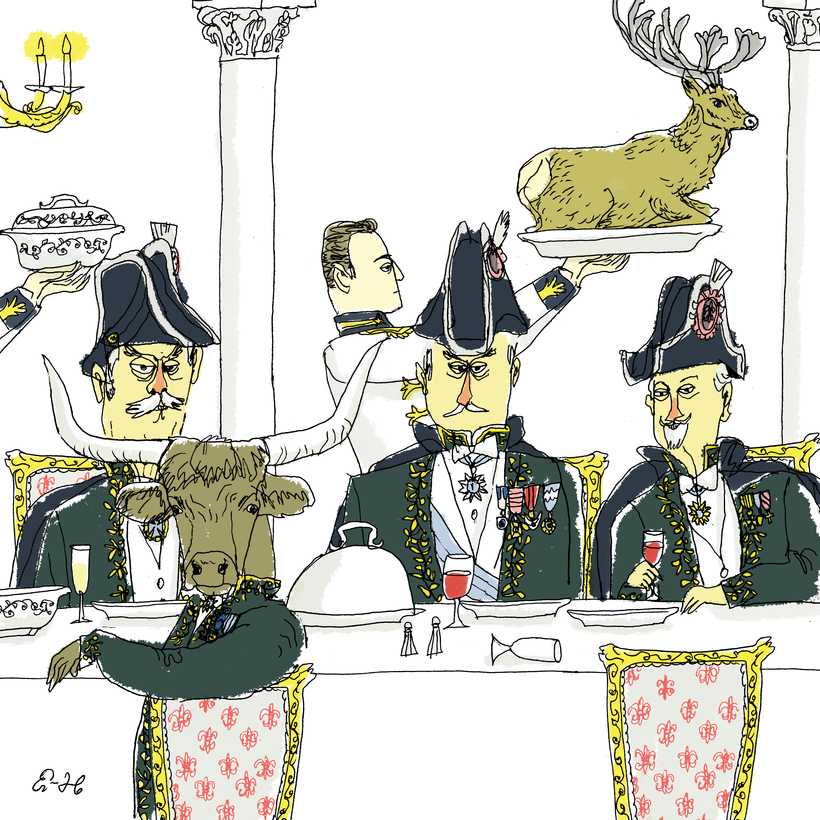

He suddenly remembered that he’d been given by his friend Pamela for Christmas, a modern edition of Vincent La Chapelle’s famous five-volume work, Le Cuisinier Moderne, first published in 1742. La Chapelle had been the chef to the Prince of Orange and in France he’d been the personal cook for the royal mistress, Madame de Pompadour. La Chapelle had visited Spain and Portugal to study their cooking, used the then-exotic food of rice, and pioneered the use of low-fat dishes. One dish Bruno recalled had used a sauce made of crushed walnuts to accompany beef, and since walnuts proliferated throughout the Périgord, he thought that might be suitable.

“Walnut sauce would be a bit dry,” Horst grumbled.

“You can’t use milk or cream in the sauce,” Clothilde said. “Our ancestors didn’t develop the lactose-tolerant enzyme until a couple of thousand years ago.”

“I could use egg yolks,” suggested Bruno. “I know chickens were domesticated much later, but there were birds and nests so eggs would have been possible.”

“What about dessert?” asked Horst. “Just offering a bowl of berries or roasted chestnuts won’t do the trick. You said the mayor wants this to be a memorable occasion.”

They agreed to help Bruno to attempt a test meal using prehistoric methods.

A Test Kitchen, Mais en Dehors

On the next Sunday morning, at a stretch of heavy, clay-filled earth on the bank of the river Vézère on the outskirts of St. Denis, Bruno dug a pit about 60 centimeters deep. He lined the bottom with flat stones and built a small fire on top of them.

Around him and watching carefully were Bruno’s friends Pamela and Florence with her young twins, the mayor, Horst and Clothilde, along with Bruno’s hunting partner, Stéphane, and Stéphane’s cousin, Silvain. As the traiteur who might have to cook this meal for 40 or 50 people, Sylvain was keen to see how this experiment progressed.

Bruno had prepared four beefsteaks, seasoned with sea salt and the tiny bulbs of wild garlic, wrapped in leaves that he’d left in water overnight and tied together with long strips of duckweed. When the fire burned down to glowing cinders, he put the wrapped steaks onto the ashes. In an attempt to get into the spirit of the ancient cooks, Bruno was using a set of prongs he’d made from two green sticks tied together at one end with rawhide. Then he covered the firepit with a large flat stone and examined the pile of duckweed that Horst, wearing a pair of angler’s waders, had harvested from the river.

The mayor had brought a picnic basket containing plates, glasses, and cutlery, along with a jar of vinaigrette that he’d made. Florence and Pamela had picked more wild garlic, sorrel leaves, and very young pis-en-lit, which Pamela called dandelions. The mayor had also foraged in the woods to dig up some fresh morel mushrooms, which looked much more appetizing than his other harvest, roots of wild radish and wild turnip, each about 10 centimeters long, thin and scrawny.

Clothilde had brought an unexpected treat, Acorus calamus, known as sweet flag, native to Europe and growing on the shallow edges of ponds and in most damp soils. The rhizomes, or rootstalks, could be harvested in autumn or spring and were used as a substitute for ginger, cinnamon, or nutmeg.

“In Roman times they were also candied and used as a sweetmeat, so I thought that might help with a dessert,” Clothilde said. “It was a very useful plant. The inner portion of young stems can be eaten raw, and the young leaves can be eaten cooked like spinach. The mature leaves repel insects, lice, and bedbugs and in medieval times, the rootstalks were used to scent clothes and cupboards. I squeezed out some of its oil, which you can use to moisten your sauce.”

In an attempt to get into the spirit of the ancient cooks, Bruno was using a set of prongs he’d made from two green sticks tied together at one end with rawhide.

As Bruno cracked an egg and began pouring the contents from hand to hand to separate the yolk, the first passersby stopped to watch. Within a few minutes, there was an interested gathering of locals along with Philippe Delaron, the local reporter for Sud Ouest, his camera at the ready. He began taking photos as Bruno crushed a handful of walnuts, added some wild garlic, and then stirred in the egg yolk.

“We are helping these eminent archaeologists to see whether we can re-create a good hot meal using prehistoric techniques,” the mayor explained as Philippe took notes. The mayor then bent to his picnic basket and brought out with a flourish a corkscrew and a bottle of red wine whose label carried indecipherable lettering, a little like Arabic but much more rounded.

“I have here a bottle of Saperavi, the oldest wine in the world, from Georgia in the Caucasus, where it was first made some 8,000 years ago,” he declared, brandishing the bottle. “And since the grape is far more resistant to heat than our own Merlot, this may be the answer to climate change. Now we have planted an experimental row of Saperavi vines in our town vineyard here in St. Denis, our prehistoric foods can be washed down in the most authentic manner.”

He opened the bottle and then took from his picnic basket several tiny plastic glasses, enough for the merest taste, poured a little wine into each one, and handed them around the crowd. Then he plucked another bottle of Saperavi from his basket, opened it, and filled larger glasses for each of the cooks and an extra one for Philippe.

“We’ll save the wine for Bruno’s pièce de résistance, which we are calling Boeuf Neanderthal,” the mayor declared.

“Is that duckweed?” asked Father Sentout, the local priest, evidently aggrieved at being given one of the tiny glasses. “I never heard of anybody but ducks eating that.”

“It’s a delicacy in Laos and Cambodia,” Clothilde said. “Full of protein.”

“Who’s going to eat this?” asked Mireille from the florist’s shop.

“We are,” said the mayor. “And if it tastes good, we might take this experiment a little further. Madame Professeur Clothilde here from the national museum thought we might smoke some fish, and our own chief of police Bruno has sketched out a design for a smoker we’re going to build. It looks like a small tepee covered in animal skins. We’re going to try different woods to flavor the smoke, starting with applewood and chestnut.”

Bruno stirred the vinaigrette into the salad of pis-en-lit, sorrel, garlic leaves, and duckweed, and used his prongs to put some onto a plate and handed it to the mayor to take the first taste as Philippe Delaron aimed his camera.

“Interesting,” said the mayor, taking a second forkful. “Not bad at all, much tastier than I expected.”

“I have here a bottle of Saperavi, the oldest wine in the world.... And since the grape is far more resistant to heat than our own Merlot, this may be the answer to climate change.”

“Stand back,” said Bruno, donning a pair of heavy gloves so he could lift the stone from his firepit, releasing an appetizing gust of garlic-flavored roast meat that stirred some appreciative murmurs from the crowd.

He used his tongs to bring out the steaks, wrapped in now blackened leaves. He used a knife and fork to unwrap them, laid them on a plate, and then smeared across some of the egg-yolk, oil, garlic, and crushed-walnut sauce he had made. He cut each steak into small bite-sized portions, and handed the plate first to Clothilde, then to Pamela, Florence, and the children, and then to the mayor and his other friends before taking a bite himself.

“Not bad at all,” said Pamela. “It’s cooked and it’s tasty.”

“This nut sauce is interesting but may need some more refining, perhaps some of that sweetmeat you mentioned,” said the mayor. “Still, it goes very well with the wine.”

“I like it,” said Clothilde. “Next time let’s try it with venison and black currants. And I’d like to experiment with the boiling stones. There’s some American research that says not to use granite since the rocks can explode so we need to get hold of some more basalt.”

“I could get a taste for this,” said Horst. “When we do the barbecue, I’ll bring along some bratwurst and good German beer.”

“Surprisingly good,” said Philippe, as Bruno handed a second plate around the crowd, but the portions swiftly ran out.

“I like it,” said Sylvain. “And I can make that, as long as I don’t have to dig too many holes, and Bruno helps with the sauce.”

“My friends,” said the mayor, “I think that we say our experiment with prehistoric food and wine has been a success. We will do more next Sunday, smoked fish and barbecued meats, mushrooms with honey and crushed hazelnuts, and different salads. Our experiments continue. But I think we can now claim that the great culinary tradition of our dear Périgord goes back some 30,000 years and we follow proudly in the steps of our ancestors.”

And that, thought Bruno, as he put aside the remainder of the duckweed for his chickens, means the next election is sewn up.

Martin Walker is a former foreign correspondent for The Guardian and the author of histories of the Cold War and the 20th-century U.S. as well as studies of Mikhail Gorbachev and Bill Clinton. Now he writes mystery stories set in the Périgord region of rural France