One balmy day last summer, I found a folder with the emblem of the Israeli secret service in my mailbox. It was a formal-looking, government-business envelope, the sort one might expect to receive from the I.R.S. or Social Security. For me, however, it was the pinnacle of a journey of historical inquiry that had lasted almost four years.

Since beginning work on my new book, Fugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold War, I had labored to gain access to intelligence-service archives, the only source where one might find reliable answers regarding the activities of former Nazi spies who evaded post–World War II punishment, roaming Cold War Europe and the Middle East in the 1950s and 1960s.

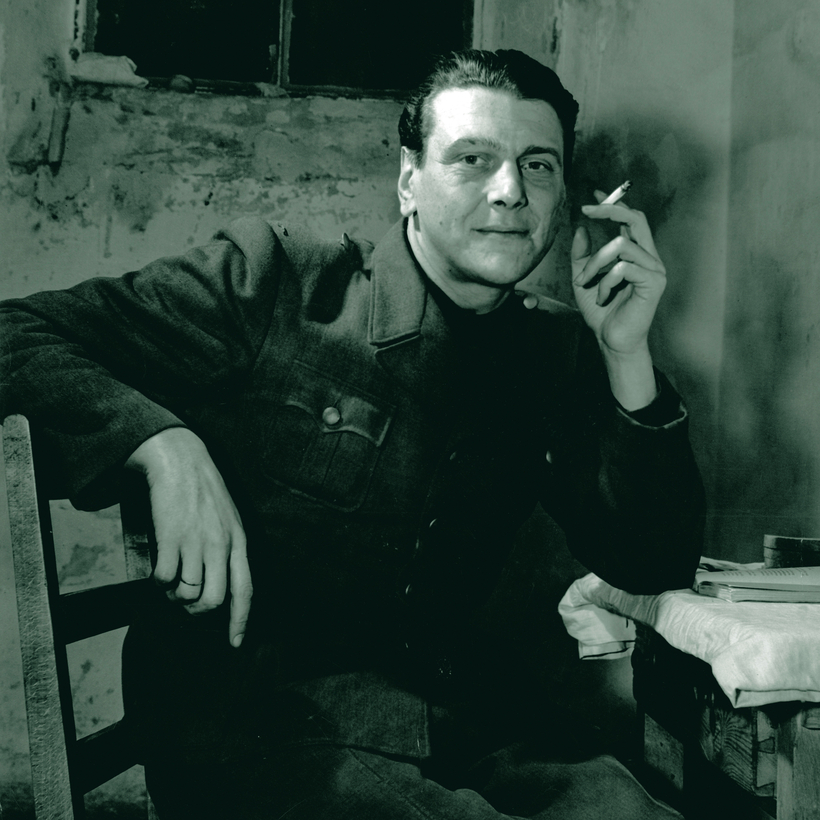

Opening the envelope, I was bursting with excitement. During my research I had come across rumors that Otto Skorzeny, Hitler’s favorite commando leader, went on to secretly work for the Israeli Mossad in the 1960s. Skorzeny, of course, strenuously denied it, boasted about his friendship with Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Jewish state’s arch-enemy, and even forecast the destruction of Israel in the next round of hostilities with the Arab world. Israeli intelligence authorities, meanwhile, did not comment on their alleged secret cooperation with the Nazi commando leader.

To the chagrin of many historians, the Mossad archives are completely inaccessible to scholars, especially in regard to such sensitive matters. And yet, the folders that the agency (God knows why) agreed to send me contained Skorzeny recruitment documents.

Page after page, they described the charged meetings between Avraham Ahituv, an observant Jew of German origins and the future head of Shin Bet (Israel’s internal-security service) and the former Nazi commander. The documents included discussions pertaining not only to contemporary espionage but also to the Second World War and the Holocaust.

To my amazement, the documents showed that the Mossad first approached Skorzeny in the most unusual of ways: by seducing his wife, with whom he had an open relationship. Through her mediation, the Mossad recruiter was able to approach the Nazi colonel.

Unlike more conventional agent recruitments, the Mossad’s relationship with Skorzeny was not based on transactional monetary compensation but rather on the weird obsession of this former Nazi with the Jewish state. For Skorzeny, it was exciting to work with his former victims, who had finally become armed, aggressive, and known for their feats of espionage.

Throughout his 11 years working with the Mossad, Skorzeny helped them gain unparalleled access to Israel’s main intelligence target at the time, the long-range-rocket program in Nasser’s Egypt, by turning the program’s security officer, an S.S. sergeant who served under him during the war.

Skorzeny’s Israeli handlers suffered from conflicted feelings as well. Throughout his interaction with the former Nazi agent, Ahituv saw his feelings shift between fascination and revulsion. Rafi Eitan, another Israeli spymaster involved in Skorzeny’s recruitment, ended up admiring Skorzeny as a “soldier of the first grade.”

I did not find evidence for this in the folder, but the Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman has even argued, based on other evidence, that Levi Eshkol, who served as Israel’s prime minister from 1963 to 1969, gave Skorzeny (not without hesitation) written guarantees that the Jewish people had nothing against him.

For me, the Skorzeny affair demonstrated not only the murkiness of the intelligence realm but also the ease with which former enemies—even victims of genocide and their executioners—can work together when circumstances change. The ability of the human mind to adapt is incredible—sometimes painfully so.

Danny Orbach is a former intelligence operative for the Israeli Army. He is a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the author of several books, including The Plots Against Hitler and, most recently, Fugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold War, out now from Pegasus