In an alternate universe, Beatrix Potter was a pioneering mycologist, not the author-illustrator of some of the world’s most beloved and enduring children’s books. Had it not been for the sexism of Britain’s late-19th-century scientific establishment, the aspiring naturalist would have found a place in science for her research on the mechanics of fungi reproduction. But when Potter, then 31, submitted a paper on the subject in 1897 to a leading (and all-male) scientific society, she wasn’t allowed to present it. The silver lining of this injustice: it led to The Tale of Peter Rabbit, an instant success when it hit bookstores in 1902. Mycology’s loss, childhood’s gain.

Opening today at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum is “Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature,” a kind of biographical retrospective. The exhibition includes many paintings and drawings, of course; on hand are renderings of familiar characters such as Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddle-Duck, and Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, along with the aforementioned mushrooms and some random bats, beetles, and caterpillars. Also on display are manuscripts, letters, family photographs, personal ephemera, and the diaries Potter wrote in a secret code. All told, there are more than 240 artworks and artifacts, spanning the entirety of her life (1866–1943).

Potter was a serious student of nature even as a young girl, drawing animals in the wild while on family vacations in Scotland and the Lake District. The V&A show includes a lovely but painstakingly rendered portrait of a lime-green lizard she executed in watercolor and ink when she was 17. That was one kind of observation. She also boiled dead animals so she could examine and re-assemble their skeletons.

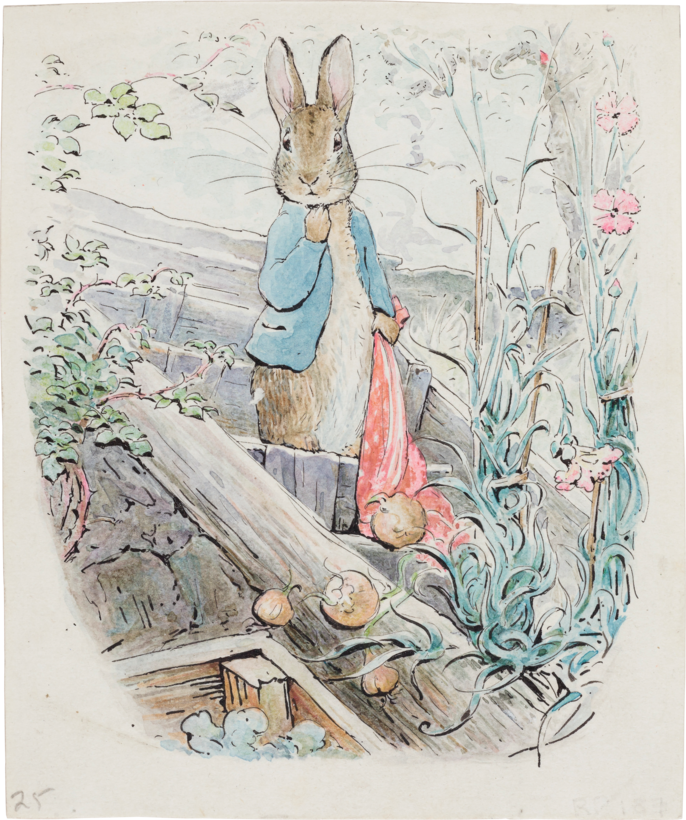

That scrupulous attention to anatomy and authentic animal-ness undercuts the whimsy of Potter’s children’s books; you may find them less cute and more peculiar, even bracing, than you remember. As Maurice Sendak, an ardent admirer, wrote of her first and most famous character, “Amazingly, Peter is both endearing little boy and expertly drawn rabbit. In one picture he stands most unrabbitlike, crying pitifully…. In another he bounds, leaving jacket behind, in a delightful rabbit bound, most unboylike.” A rabbit pelt on display at the V&A attests to the artist’s deep, even clinical intimacy with the subject.

Sendak also referred to “the hard Potter stare”—the way she refused to sentimentalize nature or anything else. After all, Peter’s story begins with his mother reminding her children to stay away from the McGregor farm, where their father was recently “put into a pie.” The peril of being eaten haunts many of her tales. This was life in the wild: the frog Jeremy Fisher may dress like an 18th-century gentleman, but he still has to worry about getting gobbled up by a wide-mouthed trout.

The hard Potter stare extended to business: she knew her way around a publishing contract and was also an eager merchandiser. The exhibition includes a prototype of a Peter Rabbit doll she herself created; it is perhaps too well executed, looking more like taxidermy than a plaything. Also at the V&A is a swath of chintz from 1923 with a pattern featuring her characters. When approached for approval, she said she liked the general design but complained, “The animals are awful. The fact that they are sketchy does not explain the want of anatomy.” Nevertheless, she signed off. In the professional wilds, commerce topped the food chain. —Bruce Handy

“Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature” is on now at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London

Bruce Handy is a journalist and the author of Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult

Discover

Discover