When Chris Pincher MP was revealed earlier this year to have drunkenly groped two men at “a London club”, the location of the outrage was soon revealed. It was the Carlton in St James’s, founded in 1832 by Tory peers and MPs after their defeat in the Reform Act.

This didn’t always guarantee it a reputation for moral rigor. As Seth Thévoz, the author of the new book Behind Closed Doors: The Secret Life of London Private Members’ Clubs, told a newspaper, the groping area has long been known as “Cads’ Corner” because men could peer up the skirts of female guests as they climbed the staircase. And the club has often been considered a haven of ambitious fortune-seekers. On his deathbed, the Duke of Wellington said his two great lessons in life were: “Never write a letter to your mistress, and never join the Carlton Club.”

Gentlemen’s clubs have been a cliché for English stuffiness, imperial conceit and boneheaded misogyny for centuries. Sometimes it feels as though they exist only to provide whiskery anecdotes about their strict observance of rules. I like the one about Percival Osborne, who joined the Travellers Club in 1889. During a bout of insanity in 1905, he shot himself through the head in the club’s billiard room. The chairman was outraged. “A gentleman,” he said, “commits suicide in the lavatory.”

Thévoz, the author of Club Government: How the Early Victorian World Was Ruled from London Clubs, offers much more than tales of delicious eccentricity, pink gins or popping monocles. He’s a serious researcher and offers a lively, exhaustively comprehensive, soup-to-cigars history of this cozy but often corrupt institution.

He’s keen to debunk myths. He points out that the first club wasn’t in London, but America: the South River Club in Maryland, founded in 1690. Its members were just 30 English colonists in a big shed, but it featured the crucial trappings of clubdom: servants, strict rules and a ballot for electing new members.

Also, the chap behind the first London club, White’s, founded in 1693, wasn’t a posh Briton but an Italian immigrant, Francesco Bianco, who set up White’s Coffee Shop in St James’s, hoping his grand neighbors would give his shop cachet. They did — a gambling room was added and the club moved to bigger premises across the street.

It’s startling to discover the modest origins of other mausoleums of privilege. London’s second-oldest club grew out of Almack’s, a Pall Mall tavern whose head waiter was one Edwin Boodle. Thévoz gleefully punctures the notion that clubs were a male bastion. In the 1760s ladies’ clubs flourished in the form of “salons” to which hundreds of both sexes flocked for dances. Getting access to larger ones meant buying tickets, and despotic lady patronesses decided who was eligible. So joining men’s clubs meant no longer having to toady to the whims of capricious Lady Boobys.

Behind Closed Doors gallops through Pall Mall, St James’s and Piccadilly, showing how clubs proliferated like giant hogweed through the 18th and 19th centuries. Profits from the slave trade created a new moneyed class of clubmen among whom gambling and drinking reached epidemic levels — but the founding in 1799 of the first members-owned clubs meant they were treated as more than up-market boozers with roulette facilities.

We read about the rise of specialist clubs such as the United Services Club (for former soldiers and sailors) and the Garrick (actors). We’re told about the Victorian club craze for celebrity French chefs — especially, at the Reform, Alexis Soyer, whose ostentatious carving of roasts or flambéing of pigeons right at the table in front of diners was an early sighting of gastronomy as theater.

We discover the wave of “reciprocal” clubs that spread across the empire so that British expats could establish a charming simulacrum of Bucks or the Savile on foreign soil (but could bring their wives). We discover that many club members were (and are) gay or bisexual; as Thévoz delicately puts it, “single-sex clubs are perfect homosocial and homosexual environs in which to unwind”. It was a tough break for the Albemarle, London’s first mixed-sex club, that Oscar Wilde was a member. When, in 1895, the Marquess of Queensberry left his card saying “For Oscar Wilde posing somdomite”, all manner of litigious hell broke loose. Thereafter, ironically, mixed-sex clubs in London were regarded with suspicion.

After the First World War old clubs stagnated. Many members had signed up to fight and failed to return. Many clubs were requisitioned for war work and failed to readjust. A noticeable fossilization set in. Old members were dying out and postwar conditions didn’t make clubland enticing for the young. Where 400 clubs once stood, now barely 200 survived; fewer than 50 made it into the 1980s.

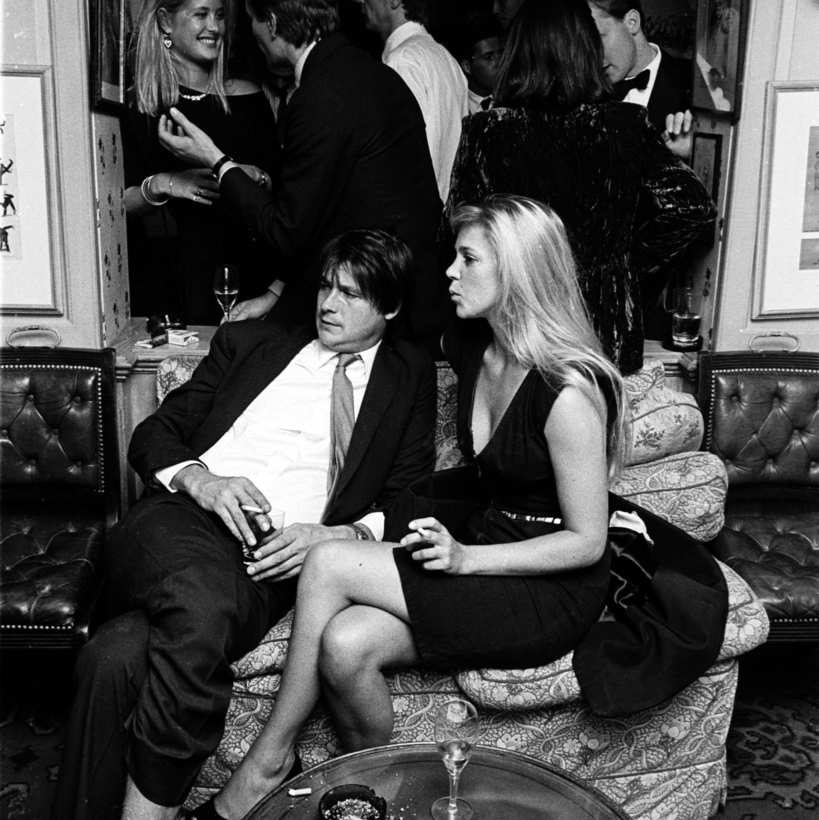

Yet Thévoz points to a remarkable resurgence after 1985. The Groucho, Blacks, Soho House and Home House were founded by a new demographic: yuppies. Arty, media-savvy, big-spending nighthawks turned some areas of London, especially Soho, into trendy retreats for the well heeled and groovy.

Meanwhile, a 40-strong rump of the classic clubs continues to flourish. Some embrace their fusty image, while some try to be more entrepreneurial or scandalous. They might be unwise, though, to repeat the Reform Club’s decision in 1978 to let their premises for a fashion shoot, only to discover that photos of 19-year-old Paula Yates, draped stark naked over the club sofas, formed the centerfold of Penthouse magazine. Misbehavior in gentlemen’s clubs will out, I’m afraid. As Chris Pincher discovered, to his cost.

John Walsh is a former literary editor for The Sunday Times and editor of The Independent Magazine