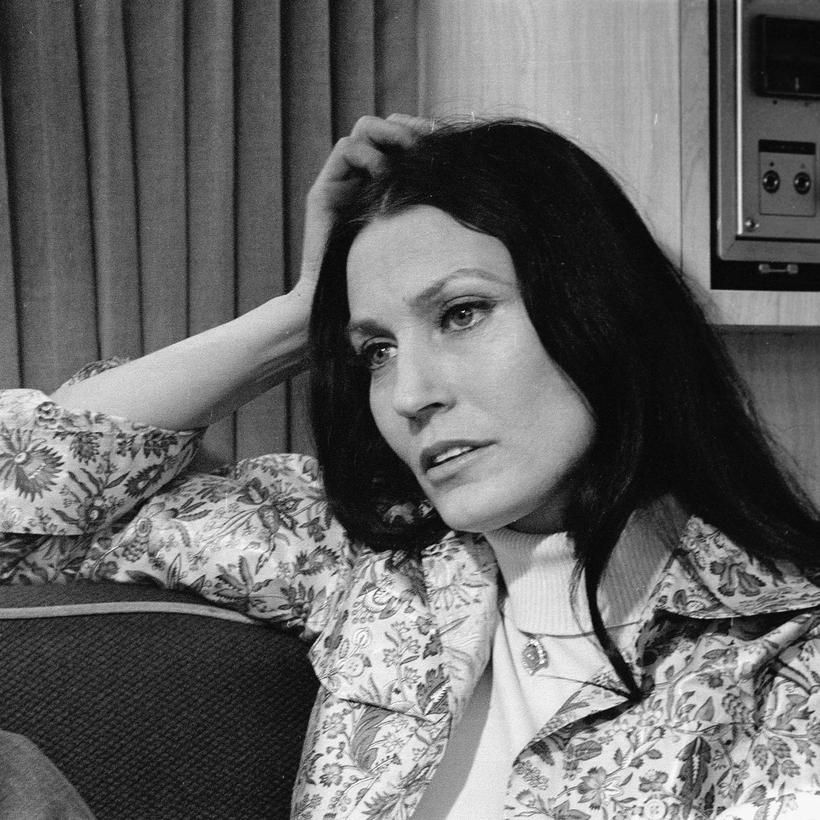

“You’ll never know you’re not in your own bed,” Loretta Lynn said to me.

It was April 1974, and we were lying on her tour-bus bed, a king-size that snapped together from the walls and filled the rump of the bus. The walls themselves were upholstered in puckered white leatherette and oozed recorded sound from tiny metal speakers. “Satin Sheets” was playing as I boarded.