The Russians have become grave robbers. Late last month, a squad of President Putin’s special forces embarked on an unusual secret mission in Kherson, close to the southern front, as the Ukrainians advanced. They were not storming a bastion nor slaughtering civilians but raiding a stone tomb in a cathedral. Their target was a body — the body of a man who had been dead for more than two centuries.

This was not just any heap of bones but the body of the most dazzling statesman ever to rule Russia: Serenissimus Prince Potemkin, the partner of, and co-ruler with, Catherine the Great. Importantly, Potemkin was also the conqueror of south Ukraine and Crimea, so not just any old Russian hero, but a titan with special significance for Putin — as I know from personal experience.

“We transported the remains of the sacred prince that were in St Catherine’s Cathedral,” announced Vladimir Saldo, the head of the Kherson military-civilian administration, on Russian TV, describing Potemkin like a saint. “Yes, we transported Potemkin himself.”

The news took me back to 22 years ago, when, as a novice historian researching my biography of Catherine the Great and Potemkin, I visited St Catherine’s Cathedral. There, Father Anatoly told me that nobody had seen the coffin inside the tomb in living memory. Nevertheless, he opened a trapdoor and led me underground into the tomb. The coffin was black and battered, with a cross on top. He opened the lid. A dank smell mixed with that of incense. There was the skeleton, the skull with a hole drilled in it from the embalming procedure. All that power and splendor reduced to this.

After the Russian Revolution, Stalin asked: “What is the genius of Catherine? Her greatness lay in her choice of Potemkin.” But in public he disapproved of Catherine’s matriarchy and Potemkin’s decadence, preferring Peter the Great. Few studied Potemkin for 70 years. This was why, in 2000, a debut biography by a young Englishman caught the attention of a young President Putin — then hailed by President George W Bush and prime minister Tony Blair as a liberal reformer.

Laura Bush revealed that, in preparation for a visit to St Petersburg in May 2002, her husband read Catherine’s love letters from my Catherine the Great & Potemkin. Meanwhile, in Moscow, Putin’s fascination with Potemkin was growing. While the book was being translated into Russian, Putin’s apparatchiks met me twice, once in the Metropol hotel in Moscow, once in Claridge’s in London, confiding to me that the president was considering the adoption of Potemkin as his model ruler. They asked if I could write “a one-pager explaining to a certain personage” how Potemkin took Crimea and south Ukraine — which I duly did.

When Bush arrived at the Hermitage Museum, Putin took him not to see Peter the Great’s portrait, but that of Potemkin. A presidential aide told my publisher that Putin had read the book and offered me my own room in the archives and the chance of first access to Stalin’s personal archive. This research became my 2003 book, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. But when it was published, Putin hated my portrayal of the dictatorship. When I returned to write Young Stalin, the archives were closed to me. Such are the whims of autocrats.

The president was considering the adoption of Potemkin as his model ruler.

When Putin annexed Crimea in 2014, I recalled that he had requested and read my work. It was an unsettling feeling but it made sense: even 22 years ago, he was fixated on Potemkin’s conquest of Crimea and Ukraine. So I was not surprised when he invaded Ukraine in February, citing Potemkin and his paladins Suvorov and Ushakov in his speeches — and it is disturbing that his misreading of my book may have played into his warped and deadly obsession.

What does Putin see in an 18th-century prince? When I studied Russian history, I noticed few writers had attempted a biography of this extraordinary eccentric and his astonishing double act with Catherine the Great. She was a diminutive German princess, intensely intelligent, boundlessly ambitious and uninhibitedly lascivious, curvaceous, with blue eyes and auburn hair. She arrived at the terrifying Russian court to marry the poxy jackanapes Peter III, who mistreated her, outraged the Russian court and was overthrown in June 1762 in a coup led by his wife, orchestrated by her lover Grigory Orlov, who soon after oversaw the emperor’s murder.

As she rode in her carriage to take St Petersburg, a 22-year-old guardsman rode on the back: Grigory Potemkin, son of provincial Russo-Polish gentry, a strapping 6ft 1in with thick auburn locks, famously beautiful, intellectually brilliant, philosophically mystic, perennially priapic and wildly ambitious. He fell in love with Catherine, ten years his senior. But she resisted him, realizing that his autocratic personality and boundless drive meant she would have to share power. The golden boy matured when he lost an eye in a fight, which earned him the nickname Cyclops.

Ten years later, Catherine, facing multiple crises, summoned Potemkin, embarking on a passionate love affair. “Can one love anyone else after loving you?” she wrote to him, calling him, variously, Tiger, Cossack Colossus, Golden Cockerel. “There’s not a man in the world that can equal you … I’ve given strict orders to my body down to the last hair to stop showing you the slightest sign of love. Oh Monsieur Potemkin, what a trick you’ve played to unbalance one of the best minds in Europe! What a sin! Catherine II a prey to such passion!” Some of her love letters were shorter: “Me love general; general loves me.”

She was orderly, disciplined, Germanic; he, wild as the steppes, sleeping all morning, up all night, wandering through her court in a pair of harem pants, gnawing on a turnip, or, in the most sumptuous uniform, advising her in all matters. But they recognized they were “twin souls”, born potentates.

Catherine and Potemkin were probably married secretly, which explains his special quasi-imperial status. When the sexual passion and jealousy threatened to destroy them both, they negotiated a unique open marriage and political partnership. He became her co-ruler and each took young lovers: Potemkin seduced his famously beautiful nieces, who, bizarrely, became Catherine’s best friends and almost her daughters. Catherine took ever-younger lovers, who had to call Potemkin batushka — Daddy.

She resisted him, realizing that his autocratic personality and boundless drive meant she would have to share power.

I don’t know what Putin makes of their love story, but their real partnership was political, and that’s why Potemkin is important today. In the 1770s, he and Catherine devised a plan to expand the Russian empire into what is today south Ukraine. Russian imperialism is rightly despised after Putin’s vicious war — and they were most certainly imperialists. But in those days, the region was ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan, the Tatar khans of Crimea, their allies the Ottoman sultans, and a community of Cossacks.

Between 1774 and 1791, Potemkin secured by war and negotiation the Ottoman swaths of south Ukraine; in 1783, he annexed Crimea. Potemkin was a statesman, a marshal, an admiral, but also a visionary. He and Catherine were children of the Enlightenment who envisioned their new Russia as the link between Europe and the Near East. Potemkin founded new cities — Kherson, Mariupol, Dnipro, Mykolaiv, Odesa — which he settled with Greeks, Italians, French, Jews, Germans and Poles, as well as Ukrainians and Russians. Most importantly, he built the naval base of Sebastopol and Russia’s first Black Sea fleet.

Uniquely for a Russian ruler, Potemkin adored other nationalities — he traveled with an entourage of his own rabbis, mullahs, French, Spaniards and Germans — and Britons. He loved everything English: Catherine bought Sir Robert Walpole’s art collection and he commissioned Joshua Reynolds; he lived in sultanic splendor, building new palaces, surrounded by a harem of paramours while his serfs transported an English garden that was planted each day so he could enjoy it wherever he was. When George III faced the American Revolution, Potemkin offered a Russian army to crush them.

Catherine took ever-younger lovers, who had to call Potemkin batushka — Daddy.

Fearing what Catherine’s jealous, demented son Paul would do after the empress’s death, Potemkin hoped to become king of Poland, but he died before her, in 1791, aged 52, out on the Moldovan steppe, weeping and reading Catherine’s love letters. A Cossack guard justly commented: “Lived on gold, died on grass.” Catherine was heartbroken at the loss of “my friend, my pupil, my idol … there’ll never be another Potemkin”.

His enemies at court and abroad claimed the cities and fleets were never built — yet eyewitnesses and my own research proved they were real. Yet “Potemkin village” entered the vernacular for a political fraud — especially since it described the mendacity much favored by the Russian state.

Potemkin’s vast neoclassical Tauride Palace in St Petersburg is today the headquarters of Putin’s Commonwealth of Independent States, and the snatching of his remains is a necropolitical statement of the Russian right to Crimea and Ukraine, Kherson and Odessa.

What will Putin do with the body of Potemkin? I predict he will orchestrate a plangent, vulgar televised extravaganza burial of Potemkin, to the sound of fireworks, folk crooners, spangled dancers and synthesizer music, in a flashy new Moscow tomb, gaudily listing his cities and conquests, to promote his war and empire.

The irony is that Potemkin and Catherine envisioned a different Russia: they were enthusiastic imperialists and autocrats, yet they were proudly pro-Western, enlightened cosmopolitans, friends of Voltaire, Diderot, Jeremy Bentham — the opposite of today’s crude, cruel Russian anti-Western ultra-nationalism.

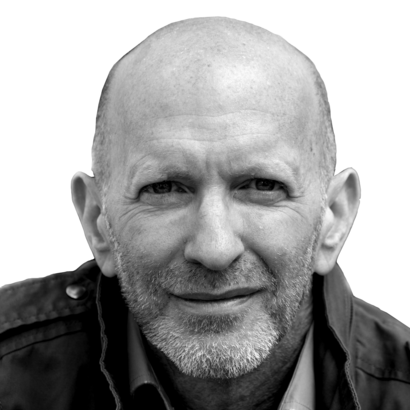

Simon Sebag Montefiore is a British historian and novelist. His award-winning books, including Catherine the Great & Potemkin: The Imperial Love Affair, have been translated into more than 48 languages