“Live there well, and never come back,” people in Russia sing ironically to their departing friends at good-bye parties, which are now as omnipresent as Zoom meetings were in the beginning of the pandemic. As friend circles, work teams, families, and neighborhoods gradually become half empty, torn, and filled with silence, irony is a great coping mechanism.

Russians have been leaving the country since the very beginning of the war in Ukraine. The borders are still open, even with the draft going on. Leaving seems to be implicitly approved of by the government, and some people are even quite openly presented with the choice between emigration and jail (such as the opposition politician Ilya Yashin, who chose the second option).

As our government occupies our neighbor’s land, people in Russia are losing their own land without any foreign invasion. That is one of the reasons why many people leave: those opposing the war can now feel alien in their homeland on an everyday level, not accounting for all the dangers of dissidence. That is also one of the reasons why many people stick to staying: out of spite, sheer obstinance, and a desire to subvert the regime’s logic.

As friend circles, work teams, families, and neighborhoods gradually become half empty, torn, and filled with silence, irony is a great coping mechanism.

We don’t have any clear borders anymore: the four Ukrainian regions that have lately been incorporated into our territory on paper have every chance of being swiftly reconquered, with Kherson already having been won back. If the case of Crimea might have seemed exceptional to some, now our occupation has become too vast, too violent, and too impermanent or unsuccessful.

It can seem that difficult times always make people come together, but this slow process of parting with one person after another rather inspires an individualistic, untrusting way of life in which you try not to become attached to anybody just to end up in different countries next month. It’s like a ghost world here—if only our government regarded us as ghosts, too.

Those who have decided to leave and are now preparing for their departure acquire some aura of already being far away, even as they are physically still here. Very often future emigrants start distancing themselves months before actually going. Their dissociation seems like the pandemic inside out: physically together; emotionally worlds apart.

I have seen many friends of mine go through this. They suddenly don’t know how to talk to you—and you feel at a loss, too. The only act of human communication still accessible for both of you is to meet at their good-bye party, drink, dance, and laugh together (not feeling any real joy and mostly acting), and in the very end of the evening go look at the moon in silence, share an extremely firm and long hug, and repeat “I love you” to each other 15 times in a row.

Very often future emigrants start distancing themselves months before actually going. Their dissociation seems like the pandemic inside out: physically together; emotionally worlds apart.

We have empty rooms and apartments, which are now very difficult to rent out (especially big and expensive ones). Finding a place to live has never been so easy. Some of my poor student friends now live in their former teachers’ apartments for free.

As for tips for street style in Moscow: Combine that scarf given to you by one departing friend with that dress you got for nothing from another one. Add some shadow to your eyebrows with that pencil your sister left. People can’t take most of their stuff to another country, so they just donate it. Brands may have closed their local stores, but I have a Burberry coat now. It’s no compensation for human connections, but it feels funny to wear it to protest rallies.

No surprise that those who emigrate are mostly people with apartments and trendy clothes to share—going is obviously a costly task.

Sadly, I can’t show off in my new coat at my former favorite hipster café. Because of its location, near a recruitment office, it is now used as a place for soldiers to say good-bye to their families. A collection of vinyl, stylishly worn-out chairs, posters for past artsy performances in a now closed liberal theater—this is the environment in which many mothers see their sons for the last time, holding hands over a cup of fancy latte.

We have empty rooms and apartments, which are now very difficult to rent out (especially big and expensive ones). Finding a place to live has never been so easy.

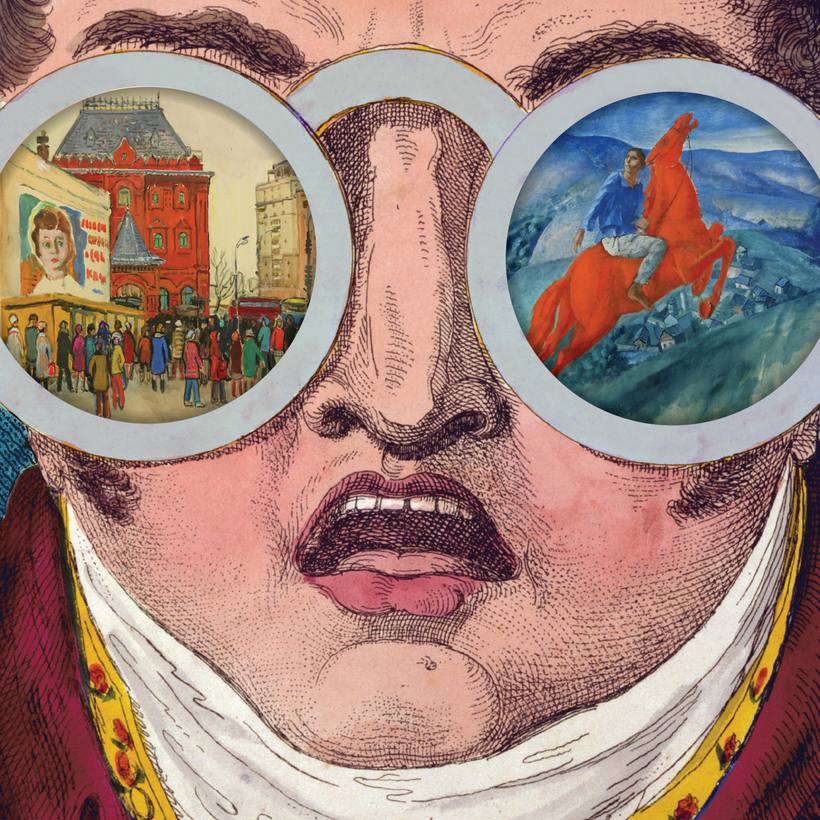

So Russian society now consists not only of devoted Putinists and tacit conformists but also of the poor, the obstinate, and the saboteurs—haunted by the digital presence of many who left (and their very noticeable physical absence, which feels like a thousand holes in the air). The state-controlled media tries to create an effect of people reconciling in patriotism, joining the queues to draft boards and pro-government demonstrations—like in some feeble parody of Triumph of the Will. But the fact is we are now a disseminated nation—to an extent at which I don’t know when to say “we” and when to say “they.” We are fighting a colonial war. They are accounting for it with anti-colonialist rhetoric. A whole new case of grammar.

There is something as serene and solemn as an ancient Greek tragedy to watching your country—which has never been perfect but in the last two decades seemed more or less tolerable—become unlivable very slowly, step-by-step, and with nobody else to blame. I still don’t want to leave (being lucky enough to be female and not subject to the draft). I still can’t believe that all of this is real. Many can’t, and this irreality is one of the main topics of party conversation.

The pinned message in one of my friend group’s chats is: “Someday we’ll wake up from this nightmare.” But for now we come from work, where we are asked to deliver our phones from all dangerous subscriptions; finish our volunteering work for the day as well as our jobs of staring at the wall contemplating the patchwork of contradicting narratives which is Putinism for the day; cover our faces in glitter, grab a bottle of wine, and set out to see a friend off, hoping that the little moments of love and togetherness, to which we break through all despair and apathy in our hearts, will help us endure.

To hear Katya V. reveal more about her story, listen to her on AIR MAIL’s Morning Meeting podcast

Katya V. is a poet, a feminist, and a tutor of Russian and English