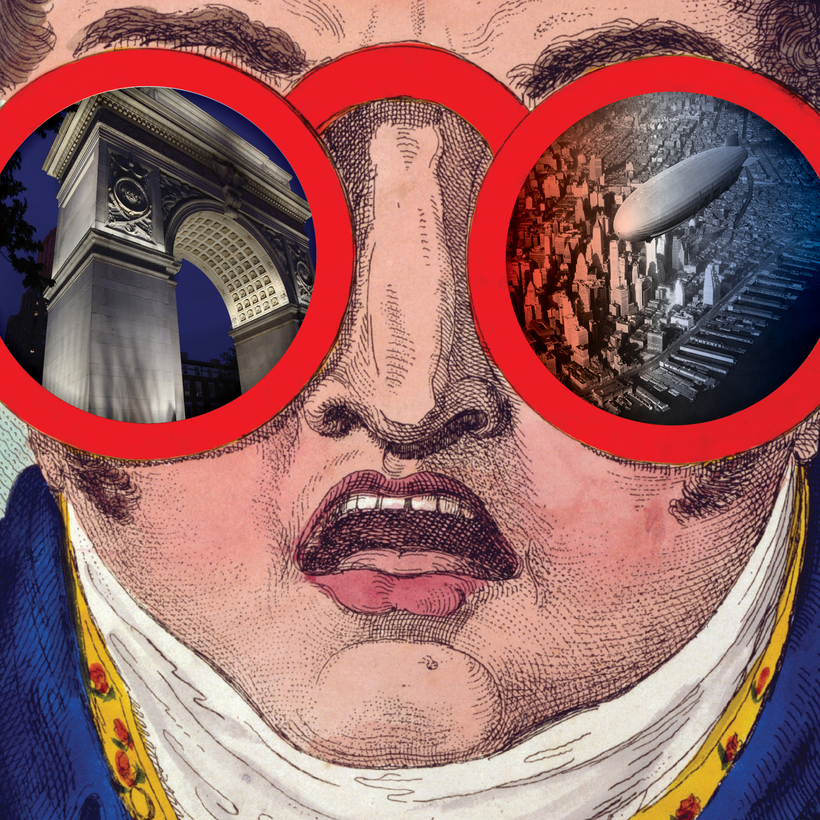

Because they need attention for survival, scenes—places where important things are thought to unfold—are not only infantile and self-absorbed; they are absurd. And so, that which has the potential to blossom into a righteous breeding ground for art and culture first appears in the public consciousness as a dartboard for ridicule, a blight on society, and, quite frankly, a bit of a sham.

There’s a reason why when we accuse someone of “making a scene” it’s usually meant as an insult. Truthfully, in New York City it almost always is. Here, all scenes are guilty until proven innocent.