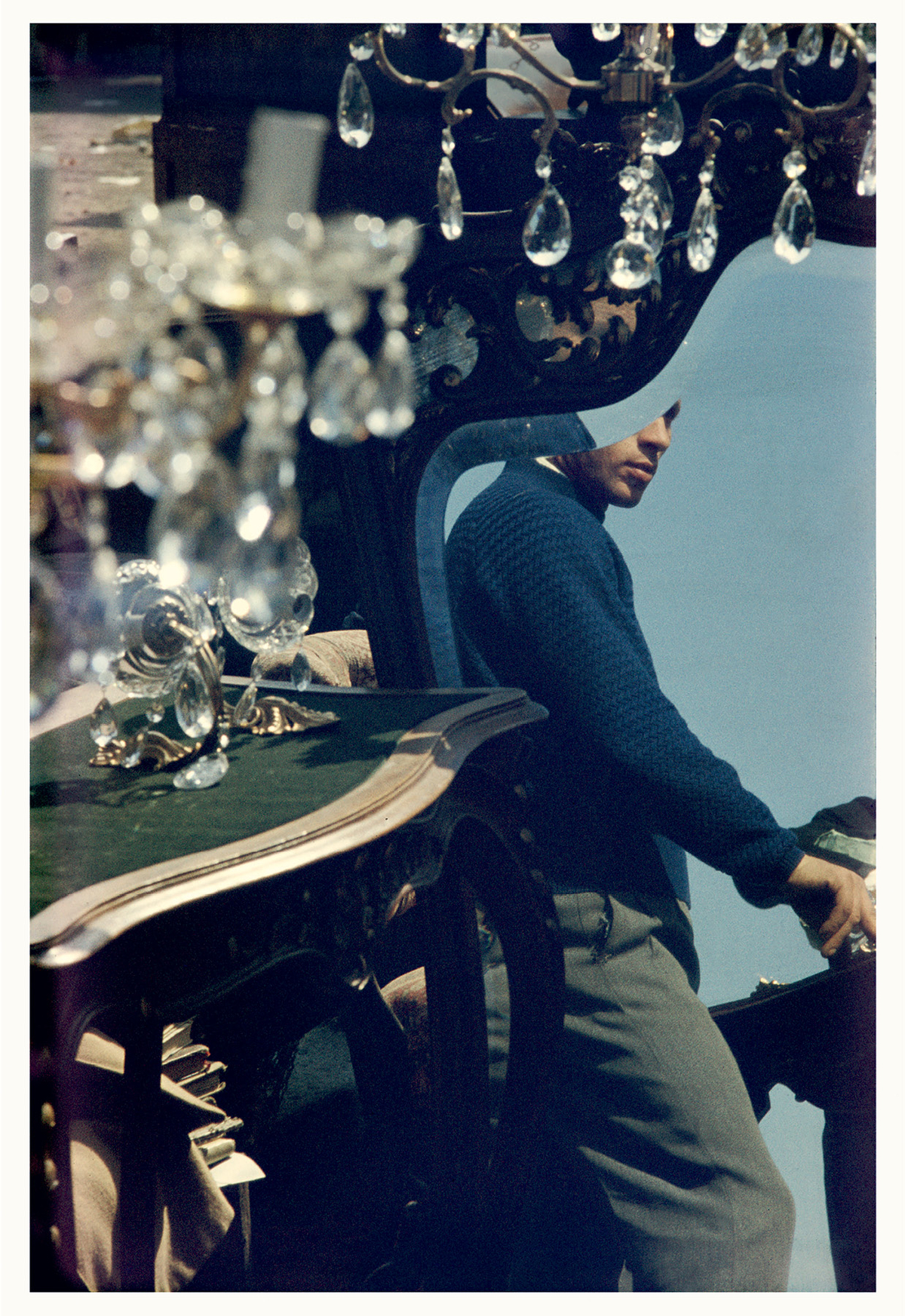

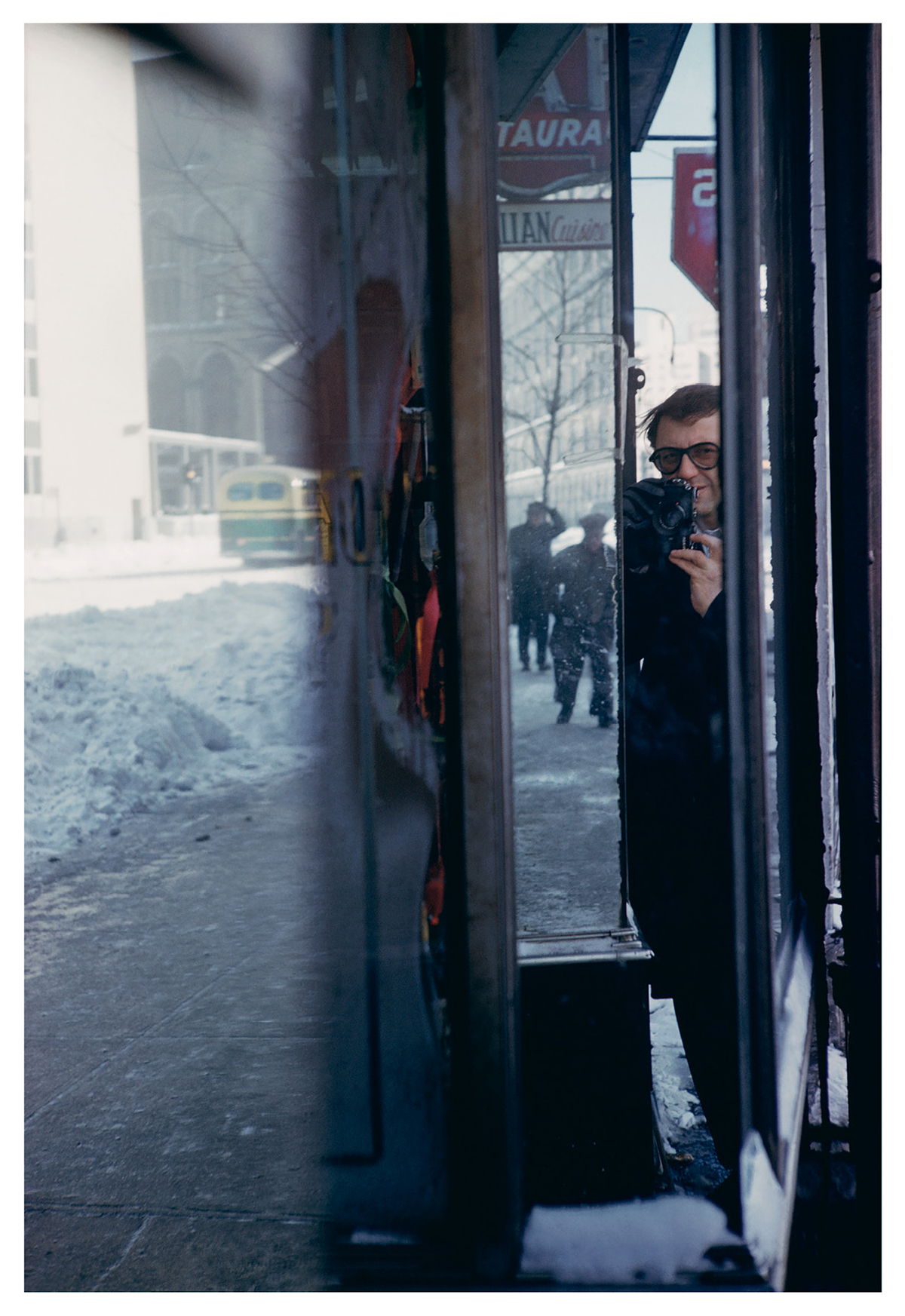

It’s quite a task to strike the right tone when admiring the work of the photographer Saul Leiter, who had little if any interest in the typical cravings of the ego-driven artist: praise, fame, success, money. Leiter saw this shiny bundle of worldly accoutrement for what it too often is, scraps doled out to the most enslaved of strivers and workaholics, and he didn’t want to be either. “In order to build a career and to be successful, one has to be ambitious,” he once said. “I much prefer to drink coffee, listen to music and to paint when I feel like it.”

It wasn’t a pose. It was a point of view, and it defined how Leiter lived his life and where he aimed his camera.