The San Francisco artist Joan Brown loved to get dolled up and go ballroom dancing. Having survived childhood with an alcoholic father and a suicidal mother, a near-death competitive swim from Alcatraz to San Francisco, and all but her fourth marriage, she was, as she put it, “an eternal optimist.” Her work careened between figures swollen with paint as thick as frosting and flat, colorful still lifes with decorative elements. Brown was in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) by the time she was 22. Tragically, she would die in Puttaparthi, India, just 30 years later, accidentally killed by a collapsed turret as she was installing an obelisk made to honor her guru, Sathya Sai Baba.

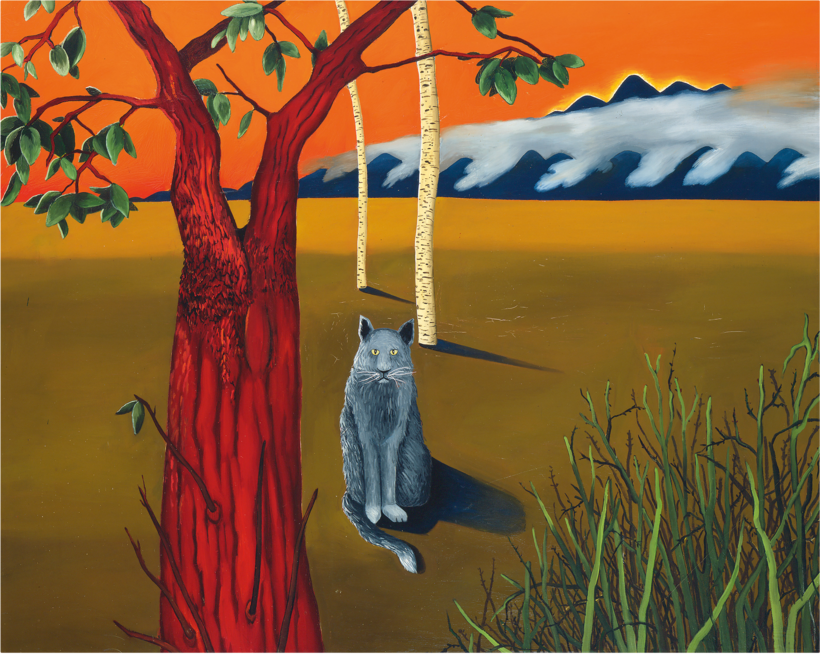

If the name Joan Brown doesn’t conjure up a specific image, it’s because she is impossible to classify. For Brown, painting was a diary that served to reinforce her mercurial existence. She believed in reincarnation and multiple lives, and because her art can seem the work of more than one life, it hasn’t found a proper place in art history. Now, a major retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, opening on November 19, goes a long way to acknowledging her abundant talent.