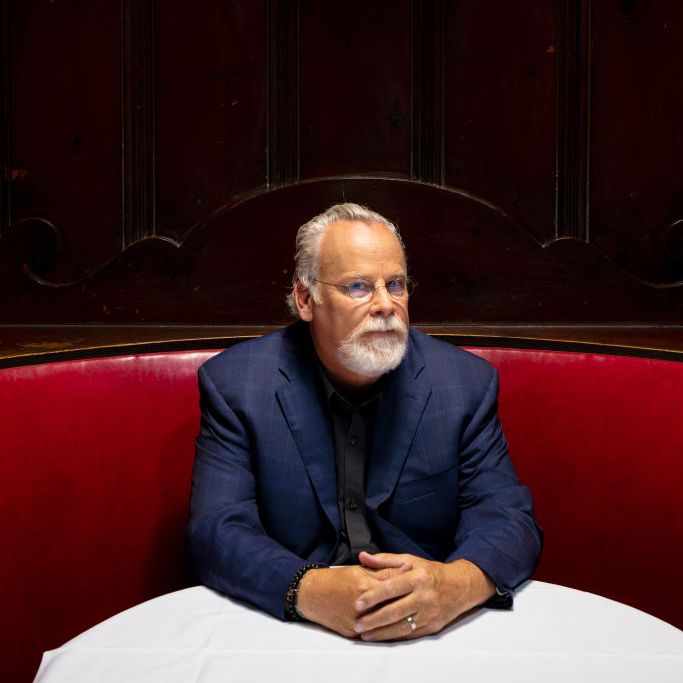

Michael Connelly is one of those former journalists turned best-selling novelists whom current journalists can’t help but envy. One they admire and respect but also, basically, whose career they want to steal. Robert Harris is another. So is Bill Bryson. And Michael Frayn. And David Simon, who co-wrote The Wire after a stint on The Baltimore Sun.

We’re not jealous of Stieg Larsson, ex-hack that he was before he wrote the Millennium trilogy, because he died tragically young. Nor Charles Dickens, because any comparison would be presumptuous. But Connelly, who quit life as a crime reporter for the Los Angeles Times in 1994, aged 38, and has published 37 books (some of them filmed for cinema and television, some of which he has executive produced), he has lived the dream.