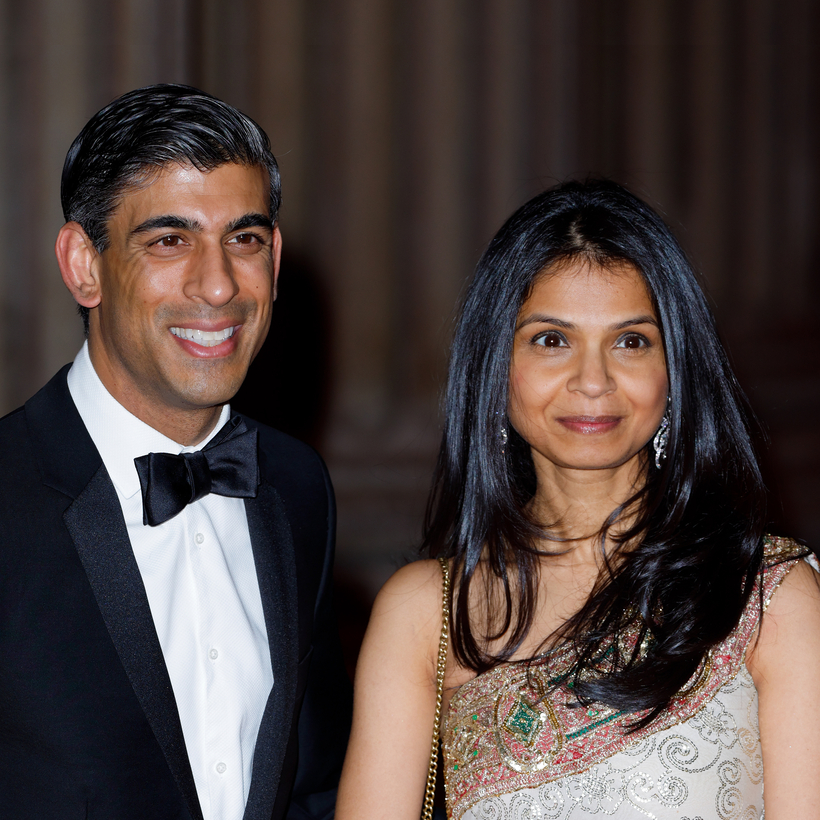

Rishi Sunak’s rise seemed inevitable. Then his approval ratings slumped dramatically when it was revealed, earlier this year, that his wife, Akshata Murty, daughter of an Indian software billionaire, had legally avoided an estimated $24 million in U.K. taxes. That scandal may have cost him his chance to succeed Boris Johnson, in September. It took the $300 billion fiasco that was Liz Truss to put Sunak back on top. —Bridget Arsenault

In a five-bedroom bungalow on a street named La Jennifer Way, a company that would change the world was just beginning to take shape. The year was 2004 and the unremarkable property with a small swimming pool that took up most of the backyard was in Silicon Valley, a part of California that was rapidly becoming synonymous with revolutionary business start-ups. Among the occupants of the house was one Mark Zuckerberg, who along with his housemates was busy building a company called Facebook. Before long, he would be one of the richest men on Earth.

No 819 La Jennifer Way in Palo Alto was normally rented out to students at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Dubbed “The Facebook House”, the property was immortalized in The Social Network, the movie which tells the story of how Zuckerberg and his team built their multibillion-dollar company. These days, the bungalow where it all started still houses Stanford students, though the landlord has expressly banned tenants from attempting to re-create the zip wire from the roof across the pool that the Facebook crew once built (destroying a chimney in the process). It was during this very exciting period in Silicon Valley history that Rishi Sunak was based there. While Zuckerberg and his gang were building Facebook, Sunak was embarking on a two-year MBA course, a hop, skip and jump away from “Facebook House” at Stanford University.

It is sometimes claimed, not entirely in jest, that Stanford MBA graduate students are not only shopping for a business qualification but also for a spouse. Many do meet lifelong partners on the course, and so it was for Sunak. Until this juncture, his love life is something of a mystery. At university, he became very close to a fellow student named Anoushka, but it does not seem that they were romantically involved. Any ex-girlfriends from his time at Goldman Sachs remain well below the radar. At Stanford, however, he would meet the person with whom he wished to spend the rest of his life: a young woman from an extraordinary Indian family whose parents were self-made billionaires.

Akshata Murty did not have a moneyed start in life. In a touching open letter to his daughter, her devoted father, NR Narayana Murthy, now the sixth richest man in India, has told how he learned of her birth through a friend, because he and his wife, Sudha, could not afford a telephone at home. “My then colleague, Arvind Kher, came all the way from our office in Nariman Point [on the southern tip of the Mumbai peninsula] to our house in Bandra [a suburb of Mumbai] to tell me that your mother had delivered you, back in Hubli, her home town,” he recalled. When Kher asked Narayana how it felt to be a father, he replied that for the first time in his life, he felt “a compelling need to become a better person”.

It was 1980, and Narayana and his wife were both struggling to establish careers. In Sudha Kulkarni, Narayana had married a force of nature: a fiery, feminist surgeon’s daughter who was highly educated and had taught her own grandmother to read. In a most unusual choice for a high-caste Indian woman of her generation, Sudha had studied electronics engineering and technology at university, becoming the first female engineer at India’s auto manufacturing giant Tata. She landed the job after firing off a postcard to the chairman complaining of the “men-only” gender bias at the firm, a move which secured her a special interview, after which she was hired immediately.

Akshata Murty did not have a moneyed start in life.

She joined the company as a development engineer in Pune. It was during this period that she met Narayana, a fellow engineer who was equally ambitious and was building a career in computer systems. They married in the late 1970s. In the early years of their lives together, the couple struggled with work-life balance, and Akshata, their first child, who arrived in April 1980, was initially brought up by her grandparents. In his letter to his daughter, published in a collection of missives from eminent parents to their daughters, Narayana explained:

“Two months after your birth in Hubli [some 300 miles south of Mumbai] we brought you to Mumbai, but discovered quickly enough that it was a difficult task to nurture a child and manage careers side by side. So, we decided that you would spend the initial years of your life with your grandparents in Hubli. Naturally, it was a hard decision to make, one which took me quite a bit to come to terms with.”

Every weekend, Narayana would take a plane to Belgaum, around 60 miles from Hubli, and then hire a car for the final leg of the journey to see his daughter. This routine was extremely expensive, but he missed her too much not to return regularly. During these visits, he was always reassured by how happy his little girl seemed, surrounded by her grandparents and a set of adoring aunts and uncles.

When Akshata was one, and Narayana in his mid-thirties, he founded Infosys, along with six other software professionals. This was the company that would go on to make his fortune. The initial capital injection, of 10,000 rupees — around $1,156 at the time — was provided by Sudha, who served as CEO from 1981 to 2001. It was not an overnight success, not least because India was such a difficult place to do business at that time. Slow processes and endless red tape meant just setting up the basics was a battle: Narayana recalls waiting a year to get a telephone connection and three years for a licence to import a computer. “We used to have a joke: half the people in the country are waiting for a telephone, the other half are waiting for a dial tone,” he has said.

In the 1990s, Infosys eventually took off. Now a multinational corporation with more than 250,000 employees, the company provides business consulting, information technology and outsourcing services.

According to Forbes magazine, in 2020 Narayana Murthy’s net worth was $2.7 billion. However, the family studiously avoids ostentatious displays of wealth. Though both Narayana and Sudha came from fairly privileged backgrounds, money was very tight when their two children were small.

On one occasion, when Akshata was at her all-girls school in Bangalore, she was selected to take part in a school drama, for which she was required to wear a special dress. It was the mid-1980s, when Infosys was in its infancy. Sudha told her daughter that it would not be possible to buy the dress and that she would have to drop out of the performance, a huge disappointment to the little girl. Recalling the episode in the letter to his daughter, Narayana said, “Much later, you told me that you had not been able to understand or appreciate that incident. We realise it must have been a bit drastic for a child to forgo an important event in school, but we know you learnt something important from that — the importance of austerity.”

She landed the job after firing off a postcard to the chairman complaining of the “men-only” gender bias at the firm.

As the couple became richer, they went to great lengths to keep their children grounded. Narayana has said that his lifestyle “continues to be simple” and that when he returns home from work every night, he still cleans his own lavatory. “We have a caste system in India where the so-called lowest class … is a set of people who clean the toilets,” he has explained. “My father believed that the caste system is a wrong one and therefore he made all of us clean our toilets … and that habit has continued, and I want my children to do that. And the best way to make them do it is if you did it yourself.”

In her quest to raise serious-minded children, Sudha went a step further, deciding early on that they should not have a television in the house in order to create more time for studying, reading, talking together and meeting friends. When Akshata and her younger brother, Rohan, were teenagers, the hours between 8pm and 10pm every night were dedicated to pursuits that brought the family together in what Narayana has called “a productive environment”. Rohan started computer coding at the age of eight. He went on to study for a PhD and became a junior fellow at Harvard before joining the family firm.

For her part, much to Sudha’s bemusement, Akshata was more interested in fashion than computers. “Ever since I was a little girl, I have always loved clothes,” she has said, adding that her “no-nonsense engineer” mother was “always baffled why I would spend so much time creating different outfits from my wardrobe”. After school in India, she studied economics and French at Claremont McKenna College in California. She might easily have finished her education there — in which case she would never have met Sunak.

Inspired by her parents, however, she was serious about making a success in the world of business. With money no object, the eye-watering fees for an MBA were no problem — and so it was that she found herself embarking on the same course as Sunak, in 2004. It is easy to see why the pair were so drawn to each other: the parallels in their upbringings are remarkable. Both had grown up in households in which education and achievement were obsessions and hard work and decency were prized above all else. Both the family units were rock-solid, and Hinduism played a big part in their lives.

At Stanford, in keeping with the way she had been brought up, Akshata never flaunted her wealth, and many of her peers were unaware that she was an heiress.

“My father believed that the caste system is a wrong one and therefore he made all of us clean our toilets.”

“I wasn’t super-close friends with her but I will say the entire time in our first year I didn’t even know that her family was wealthy,” says Maria Anguiano, a fellow student from the class of 2006. “I literally didn’t know until the second year of our business program and that was because we had a study abroad-type program and a group of students went to India and she helped organize it and that’s when I realized how important she was, but before that I never ever would have guessed because there was nothing about her that indicated that.”

Akshata played a key role in the organization of the fortnight-long study trip for fellow students, during which they met key business figures and politicians to develop their understanding of what made the country tick. The tour took in Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore, where the students were introduced to Narayana.

With outgoing personalities and preppy good looks, Sunak and his new girlfriend quickly became something of a power couple at Stanford. “I mean, I know as soon as they got together, they were quite the power couple on campus, in terms of just both very committed to each other and both very, I think, focused on making an impact,” Anguiano says. “I’m not sure if I remember them having political ambitions, but I know that they were very impact-orientated people.”

Rashad Bartholomew, who now works as an account executive at Gitlab software company in San Francisco, seconds this: “I do think they definitely complemented one another, they’re definitely a beautiful, powerful power couple, a good-looking couple, a smart couple. And I definitely think that their hearts are in the right place.”

According to Forbes magazine, in 2020 Narayana Murthy’s net worth was $2.7 billion.

There does not seem to have been much talk of party politics, but Akshata in particular is remembered as an idealist. “Folks in business school at Stanford tend to think they can actually make an impact and change the world, so that was definitely a part of just the general vibe of the campus and our program, but they actually went out and did it,” Anguiano says. Bartholomew had the same impression. “She was always interested in pushing positive social agendas,” he recalls, adding that she was especially keen to explore how not-for-profit programs could improve society.

After two incredibly formative years, in summer 2006 Sunak’s time in Palo Alto was coming to an end. He had successfully completed his MBA and now had to decide how to use it. He and Akshata also had a difficult personal decision to make. Sunak was heading back to London while Akshata, who had been in the States for many years, felt very rooted in America and had decided to stay.

She had always loved clothes and had long hoped that one day she could launch her own fashion label. To that end, she enrolled on a postgraduate course in apparel manufacturing at the nearby Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising. Meanwhile, Sunak was returning to the City, having secured a plum job at The Children’s Investment (TCI) Fund, a hedge fund run by the billionaire financier Chris Hohn. He had been recommended for the role by his old mentor Snehal Amin, who had left Goldman Sachs to work with Hohn. Amin had previously encouraged Sunak to broaden his horizons after he’d completed his three years’ training at Goldman Sachs, suggesting to his junior colleague that he consider studying for an MBA at one of the world’s most prestigious business schools.

Despite the geographic challenges, Sunak and Akshata were committed to each other and would stay together. For now, theirs would have to be a long-distance relationship. For the next few years, the couple would live between London, California and New York, the latter being a much more practical place for them to meet, if Sunak was flying from the UK. In 2009, Sunak would take up a job that allowed him to relocate to California, where they were able to live together, but for the time being it was a question of crisscrossing the Atlantic to see each other as often as work allowed.

In January 2009, Sunak proposed to Akshata. They had been together for several years, sometimes living thousands of miles apart, but despite the geography and work schedules that often left little time for romance, they both knew they wanted to be together forever. For Narayana Murthy, news of the engagement was bittersweet. “It is quite a well-known fact that when a daughter gets married, a father has mixed feelings,” he would tell Akshata later, admitting to a twinge of jealousy at having to share her with a “smart, confident, younger man”.

However, the moment he and Sudha met their future son-in-law, any misgivings evaporated. Rishi Sunak was everything Akshata had said he was. In his open letter to his daughter many years later, Narayana was gushing about her choice. “I found him to be all that you had described him to be — brilliant, handsome, and most importantly, honest. I understood why you let your heart be stolen. It was then that I reconciled to sharing your affections with him,” he wrote. The couple set the date for their wedding at the end of August 2009.

Weddings are an obsession in India and prominent families like to lavish huge sums on ostentatious celebrations. Multiple ceremonies and receptions held over several days are not unusual. So when society magazines learned that the daughter of one of India’s foremost industrialists was to be married, there was much excitement. To the disappointment of gossip columnists, however, Narayana and Sudha were not about to abandon the quiet modesty with which they had chosen to live their lives, even for their daughter’s wedding.

This would not be a crazily extravagant affair. “We’d have loved to know more about the wedding and share the same with WeddingSutra readers,” one magazine reported disconsolately, admitting information about the event was thin on the ground. “Much as we’re dying to learn this, we can’t tell you where Akshata picked the pretty pink saree that she wore for the [blessing ceremony] or the designer who designed the beautiful orange lehenga choli [three-piece traditional Indian dress].”

To say that the venue for this part of the nuptials was not flash is an understatement. A marketing video for Chamaraja Kalyana Mantapa in Bangalore shows a cavernous, utilitarian hall that looks much like a school gymnasium. The venue did not allow alcohol or non-vegetarian food. The main attraction appeared to be the sheer size of the place: it could seat 800 guests, with standing room for a further 700 people.

The wedding reception itself was held somewhere significantly more glamorous: the spectacular five-star Leela Palace hotel in Bangalore. A modern palace built in 1997 with stunning tropical gardens, a spa, and 29 suites which come with a butler service, it promises to make guests “feel like a Maharaja” and “take back memories of a regal experience”. For once, the characteristically self-assured Sunak was nervous, so much so that it appears he may have temporarily broken his lifelong habit of eschewing alcohol. A friend says, “Apparently he promised friends that he would have some shots in advance of his wedding, and he did.”

Neither the bride nor her mother wore many diamonds; nor did they indulge in the heavily embroidered outfits and gaudy accessories often favored by wealthy bridal parties. “Both the bride and her mother wore subtle make-up, a natural-look hairstyle and what by Indian wedding standards could be considered minimal and basic jewellery,” the magazine declared. There were some celebrity guests, however, including the Indian business tycoon Azim Premji, known as the czar of the Indian IT industry and a man even richer than his hosts; the Indian billionaire entrepreneur Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, chair of a biotechnology company based in Bangalore; the Indian cricketers Anil Kumble and Syed Kirmani; the former champion badminton player Prakash Padukone; and the Indian actor Girish Karnad.

What of the bridegroom in all this? The Indian press showed only a passing interest in Sunak, simply describing him as “a British citizen of Indian origin” and noting that he was a Fulbright scholar who had studied at Oxford and Stanford.

As his best man Sunak had selected his best friend, James Forsyth. The pair had been friends for more than 15 years, having been at Winchester together. While Sunak was in the City, Forsyth had gone into political journalism and was a rising star at the Conservative-supporting Spectator magazine. The following month, he would be promoted to political editor of the publication.

For now, the relationship between these two supremely bright young men was primarily personal not professional, but as Sunak became more engaged in UK politics, this would change. In time, both would become even more important to each other as they helped each other’s careers. When Sunak decided to make the leap from the City to politics, he was able to tap into Forsyth’s network of Tory contacts and insider knowledge about the Conservative Party. Later, when Sunak became chancellor, Forsyth and his journalist wife, Allegra Stratton, found themselves with a direct line into one of the most powerful political figures in the country.

Michael Ashcroft is an author, military historian, and journalist. He has written 17 books, primarily on politics