Like so many buildings in Rome, the Villa Farnesina is more sumptuous on the inside than on the outside. Stroll through Trastevere to the Ponte Sisto and keep walking along the river, and you’ll pass right by it—a palazzo like any other, set back among trees and gardens. But the interior is filled with light and color. There are frescoes by Raphael. One room is famous for an experiment in trompe l’oeil perspective.

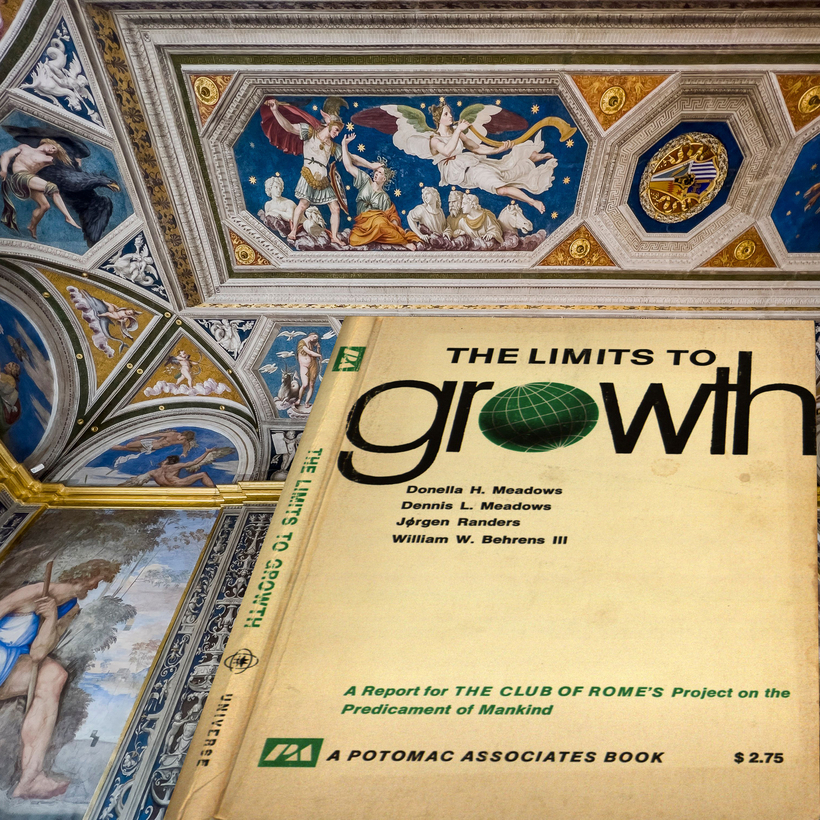

The villa was being built at exactly the moment when Michelangelo, a mile away, was painting the Sistine Chapel. Later it came into the hands of the Accademia dei Lincei, a scientific society whose original members included Galileo. And it was here, in 1968, that an assortment of midcentury grandees—scholars, industrialists, diplomats, bankers—met to create an organization called the Club of Rome. Its mission was to explore the “predicament of mankind.”