Jean-Georges is always around.

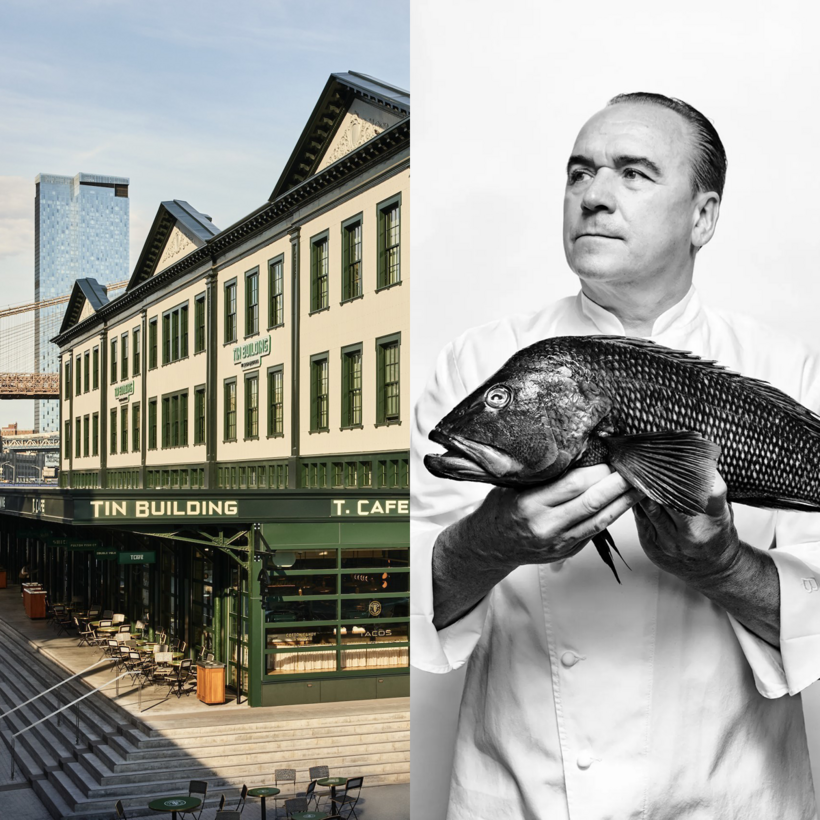

That’s what you hear when you wander through the Tin Building, the chef’s shiny new hive of restaurants and shops at the south end of Manhattan, next to the lavender underside of the F.D.R. Drive. He’s here all the time! You just missed him.