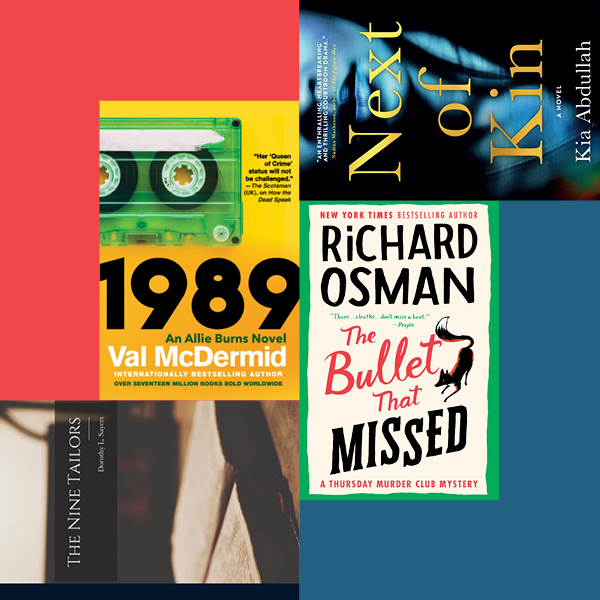

In honor of Queen Elizabeth II and the kingdom she leaves behind, this column is an all-British affair. These books reflect the diversity of its voices and stories—from the aspirations of South Asian Londoners to Scotland’s shameful response to the AIDS crisis in 1989, to the distinctly British humor of the Thursday Murder Club. If you watched the Queen’s funeral, you couldn’t miss the church bells that are such an integral part of Dorothy Sayers’s The Nine Tailors, tolling their message of mourning.

There’s a bit of royal reserve in Leila Syed, the high-achieving architect at the center of Next of Kin. Her people skills suffer in comparison to those of her younger sister, Yasmin, whom she raised when her parents died, sacrificing much while still a teenager. The composed, groomed exterior she’s perfected keeps other people at a distance, while Yasmin, looser and softer, draws them in. Beneath the mask, Leila is a devoted aunt to Yasmin’s toddler son, showering him with love and attention and picking up the slack when his parents are busy. But what happens when she volunteers to drive him to school one hectic morning sets an unthinkable tragedy in motion.

British writer Kia Abdullah has a knack for concocting ethical dilemmas, sometimes involving illness, and giving them a wrenching twist just when you thought everything had been settled. Next of Kin is mystery-melodrama of a high order, turning on an act of negligence—or is it a crime?—that resonates because it could, on the wrong day, happen to anyone.

Abdullah goes deep into gnarly questions about sisterly rivalry, society’s suspicion of professionally successful but childless women, and the third rail of family secrets. She summons up plenty of volatile emotion, then wrangles it into a charged narrative that seems poised to culminate in a London courtroom. Or not. The ground is always shifting under these characters, de-stabilizing both them and the reader to chilling effect.

The future can look especially uncertain at the end of a decade, a pivotal point in time that Scottish crime writer supreme Val McDermid is exploring in a new series. She got off to a great start with last year’s 1979, replacing her customary police detectives with an ambitious young reporter named Allie Burns, who worked for a Glasgow tabloid when newsrooms were at their raucous, adrenaline-fueled—and sexist—peak, and the digital future was only a wee green glimmer on the horizon.

Kia Abdullah has a knack for concocting ethical dilemmas, and giving them a wrenching twist just when you thought everything had been settled.

Ten years on, Allie is based in Manchester as the “northern editor,” i.e., the only person covering that area, for the Globe, owned by a barely disguised Robert Maxwell stand-in named Ace Lockhart. Several disasters occurred on Allie’s patch that year, among them the Lockerbie bombing, which opens the book, and the Hillsborough disaster (a deadly crush in a Yorkshire soccer stadium). She covered them all, at mounting emotional cost.

To preserve her sanity and do what she does best, Allie pursues an investigative story on the side, about dodgy AIDS-drug trials that Scottish Big Pharma has outsourced to East Germany, where they aren’t fussy about protocols. Allie’s way into the East German lab is a Scottish scientist whose East German lover wants to defect; together they concoct a scheme that almost gets Allie locked up in a Stasi jail for good. Allie’s unlikely interlocutor is Lockhart’s daughter Genevieve (despite the French-sounding G-name, she isn’t too much like Ghislaine), who’s also in Germany trying to protect Ace Media’s interests in the Eastern Bloc should regime change occur.

At this point, the plot pivots to Ace and Genevieve. McDermid clearly relishes the opportunity to dissect the awfulness of Maxwell/Lockhart’s many misdeeds, and creates an alternate version of the disgraced tycoon’s demise that should intrigue Maxwell-watchers. (I’m not giving anything away here—it’s in the prologue.)

So many issues for one book: the AIDS crisis, the imminent shift of power in the Eastern Bloc, Thatcherism, gay rights—it’s possible that McDermid has aimed too wide with 1989, trying to embrace a panorama of events and social change through the fallible vessel of Allie. Though well rendered, especially the soccer disaster, the tragedies she covers threaten to overstuff the narrative and pull focus from the main story. I also miss the rough-and-tumble of the newsroom, but time marches on …

McDermid is trying something new with this series, so a bit of transitional awkwardness is understandable. There are still many pleasures to be gotten from 1989, one of which is the irresistible 80s playlist that closes out the book. Rock on, Val McDermid.

The future can look especially uncertain at the end of a decade, a pivotal point in time that Scottish crime writer supreme Val McDermid is exploring in a new series.

The tunes are probably more sedate in the Jigsaw Room at the retirement community of Coopers Chase, where the Thursday Murder Club holds its meetings, but really, when it comes to this group of amateur septuagenarian sleuths, who knows? They are nothing if not unpredictable, which is part of their considerable charm. By now, everyone not living in a cave knows that the club comprises Elizabeth, who was a spy; Ibrahim, a psychiatrist; Ron, a union leader; and Joyce, a nurse, who sounds very sweet, but don’t underestimate her.

In the third book of Richard Osman’s publishing phenomenon, the fab four decide to look into a cold case—the 10-year-old unsolved murder of a local news reporter named Bethany Waites, whose car went off a cliff when she was working on a hot story involving VAT fraud, and whose body was never found. At the same time, Elizabeth is getting threatening messages from an unknown person demanding that she kill an old spy acquaintance of whom she’s rather fond. This is all a bit much for the four core members, so, by way of assistance, the club picks up some promising new associates.

I won’t say the cold case is just an excuse to turn these characters loose in incongruous situations and let them do their thing, but … the first page contains a strong hint about Bethany, and some clues are withheld till late in the game. However, I can’t imagine anyone complaining, not when you have set pieces such as Ron’s terror-stricken first encounter with a spa massage, or Elizabeth’s allergic reaction to being part of a daytime-TV-show studio audience. Osman’s formula of short chapters that often end in mini-cliffhangers is effortlessly effective, making this longish book zip by like a motorized scooter. As ever, his ear for dialogue remains blithely, hilariously perfect.

In the third book of Richard Osman’s publishing phenomenon, the Thursday Murder Club, a fab four of amateur septuagenarian sleuths decides to look into a cold case.

It is also specifically English, with faint echoes of the work of Dorothy Sayers, whose Lord Peter Wimsey novel The Nine Tailors (1934) is considered by many to be her best. The titular tailors are actually the strokes of the awe-inspiring church bells in the parish of the fictional Fenchurch St. Paul that announce the death of a man, so this book begins with a lengthy treatise about the strenuous art of bell ringing.

It takes a while to get from the bells to the actual murder, of an unidentified man whose body has been mutilated, as well as the unsolved theft of an emerald necklace. Helped by a gaggle of loquacious and observant villagers who supply comic relief and more, Lord Peter wends his way through this exceedingly tricky puzzle, occasionally overthinking as gentleman sleuths are wont to do, but seldom breaking a sweat.

Lisa Henricksson reviews mystery books for Air Mail. She lives in New York City