The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation by Rosemary Sullivan

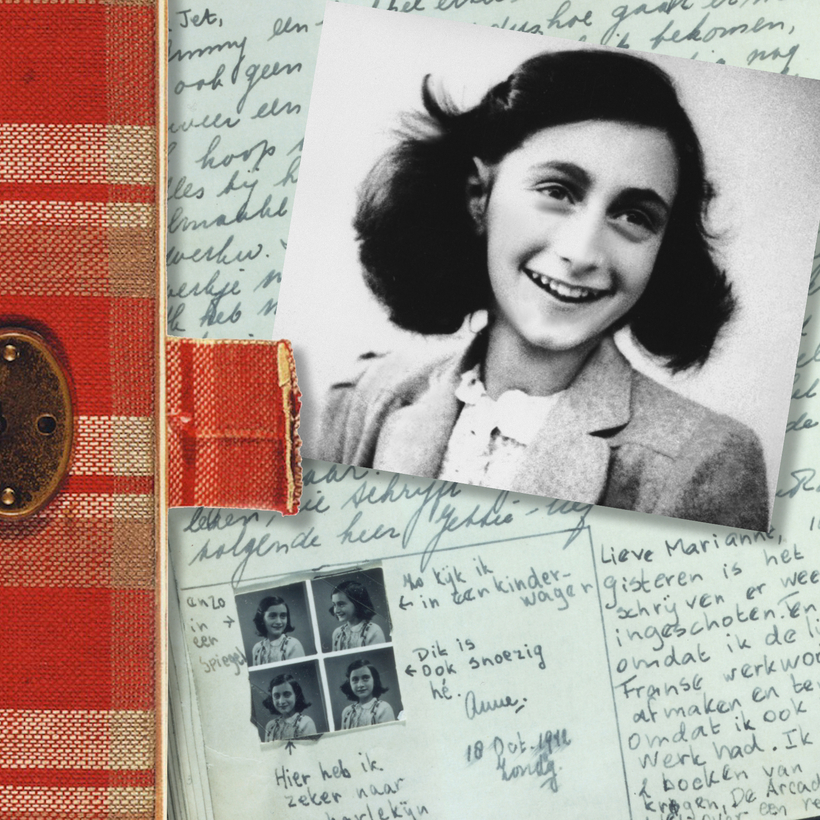

Anne Frank is a 20th-century icon and a symbol of humankind’s capacity to wreak horror on the innocent and the young. For two years, in hiding in Amsterdam, she recorded her thoughts in a diary that captures the imagination, the highs and the lows, the fears, and the hopes of a girl on the cusp of adulthood.

On August 4, 1944, just a few months before the liberation of the Netherlands from Nazi rule, she, her sister, her parents, and the Van Pels family, with whom they were in hiding, were apprehended from the Franks’ secret annex at Prinsengracht 263. Duly carted off to Auschwitz for extermination, Otto Frank, Anne’s father, would be the sole survivor (he was freed by the Soviets in 1945) and guardian of his daughter’s remarkable writings.