When my siblings and I returned from Melbourne to Kabul two decades ago, the media landscape was stripped bare. The Taliban had banned television, radio, and newspapers. Journalists from across the world had descended on Afghanistan to cover the U.S.-led war, but ordinary Afghans had no means by which to know what was happening in a nearby province, let alone the outside world.

We began our journey by setting up a low-powered FM radio station in Kabul. Within three years, with a $500,000 investment (of which $220,000 was a grant from the United States Agency for International Development), we established dozens of media outlets, including Tolo TV, one of Afghanistan’s most popular television channels, which is now seen by millions across the country.

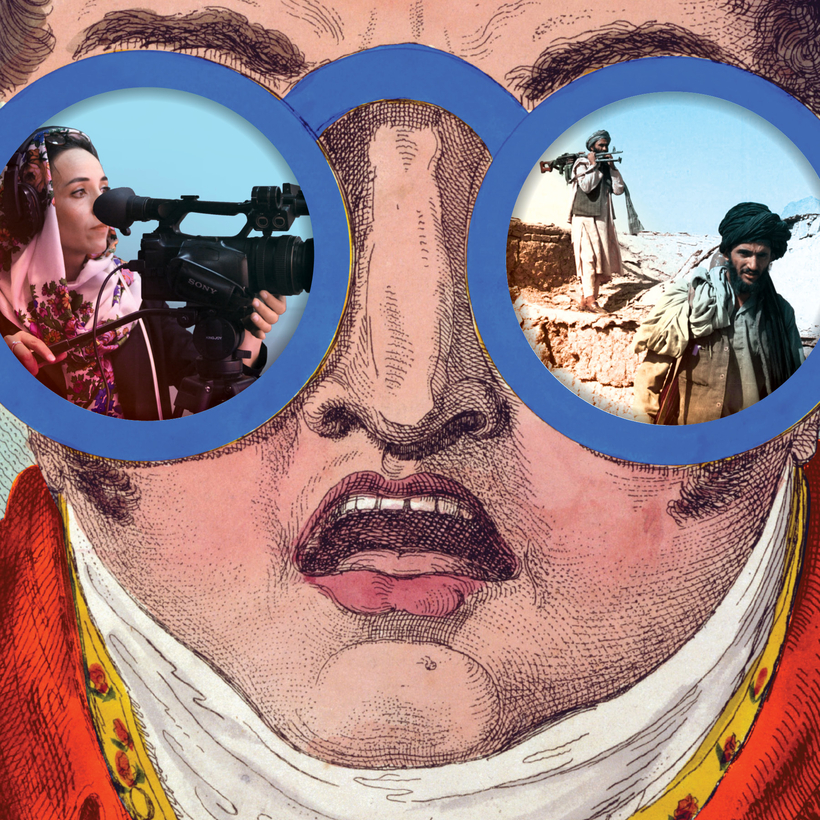

Afghanistan now has the most independent media of all the countries that surround it. There are hundreds of radio and television stations and print and online publications. Our news programs—and those of our best competitors—fearlessly report on the conflict, on the brutality of the Taliban, and on the corruption of politicians, and give the young people and women of Afghanistan a voice that was long denied to them.

Our entertainment channels promote culture, a soccer league, stand-up comedy, and pop music in the same country where the Taliban beat women, banned music, and carried out public executions in soccer stadiums. These gains weren’t granted to us. Afghans fought hard to win and defend them.

Over the past year, the Taliban and other armed groups have stepped up what Human Rights Watch described as a campaign of “threats, intimidation, and violence.” Three women media workers were killed in March in the eastern city of Jalalabad. Our journalists continue to report on the violence consuming the country, the human-rights violations taking place, and the desperate humanitarian needs of Afghan people trapped in the conflict.

Our entertainment channels promote culture, a soccer league, stand-up comedy, and pop music in the same country where the Taliban beat women, banned music, and carried out public executions in soccer stadiums.

We are being forced to rethink how we operate in such a hazardous environment, but we won’t give up. Even exile is preferable to plunging Afghanistan back into a media blackout. And it’s important to remember that such blackouts are now full of holes.

Afghanistan will not go back to the country it was under the Taliban. It now has the youngest population outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Afghans now live in towns and cities. The majority of our youth are literate and receiving an education, and have access to the Internet. More Afghans than ever accept the rights of women and minorities. The country’s media revolution has forever changed the way Afghans see themselves and each other, and how they engage with the wider world.

Our investigative-news teams have exposed corruption, including the Kabul Bank scandal and alleged ballot-box stuffing during the 2014 presidential elections. Our interviewers have confronted senior government officials on their track records in front of live audiences, including the president. At election time, we host presidential debates where candidates have their feet held to the fire. We have asked Pakistan’s and Iran’s foreign ministers questions that their own media cannot.

Our entertainment programming has revived Afghanistan’s cultural traditions—clothes, design, and artistry—and pushed the boundaries in a country where women were once banned from appearing in public without a man. Roya Sadat, the famed Afghan filmmaker who was behind 2017’s A Letter to the President, which Afghanistan submitted for best foreign-language film for the 2018 Oscars, has produced several drama series that tell the country’s stories to a new generation.

Six years before The Voice hit U.S. television screens, Afghan Star began discovering and promoting women singers and rappers. The show is now in its 15th season, and several winners have established their careers as beloved musicians across the region. Early on, we sometimes went too far in terms of stereotyping certain people and making fun of religious and political icons. But something worked.

The majority of our youth are literate and receiving an education, and have access to the Internet. More Afghans than ever accept the rights of women and minorities.

Ever since the Soviet invasion, four decades ago, many Afghans were forced to leave the country or spend their early lives abroad. The media has helped many of them re-discover their country, its history, its culinary traditions, and its humor. Travelogues now take viewers on journeys to forgotten places of heart-stopping natural beauty.

Bridging the rural-urban divide, we have given voice to tribal elders who compellingly recount the oral histories of their provinces. A program devoted to local eateries in faraway villages provokes the gastronomic envy of people in the cities—and the millions of Afghans in the diaspora, who remain connected to their country through our streaming platforms.

Making fun of powerful people is a risky business in many parts of the world. But in Afghanistan, ridiculing the political elite has become a treasured pastime. I, like so many, am appalled by the rapacious greed and notorious ineptitude that has had a hand in the re-emergence of the Taliban. But Afghans aren’t afraid to scrutinize those who have failed our hopes, especially through political satire in keenly watched Saturday Night Live–style comedy shows.

We are all worried about what the next few months will bring. The violence shows few signs of abating, and peace remains a distant prospect. Afghanistan may undergo dramatic changes that will tear at the social fabric of the country, and perhaps even tip us into an all-out civil war once more. The world can’t afford to turn away from the 38 million people of Afghanistan at this time.

The country’s media is a light that exposes the cruelties Afghans face, connects them to each other and to the world, keeps their hopes aflame. Afghans and the international community can play a key role in ensuring they don’t slip back into the darkness.

Saad Mohseni is an entrepreneur who with his siblings established the MOBY Group, now Afghanistan’s largest media company, after the Taliban was toppled in 2001