The Irish Assassins: Conspiracy, Revenge, and the Phoenix Park Murders that Stunned Victorian England by Julie Kavanagh

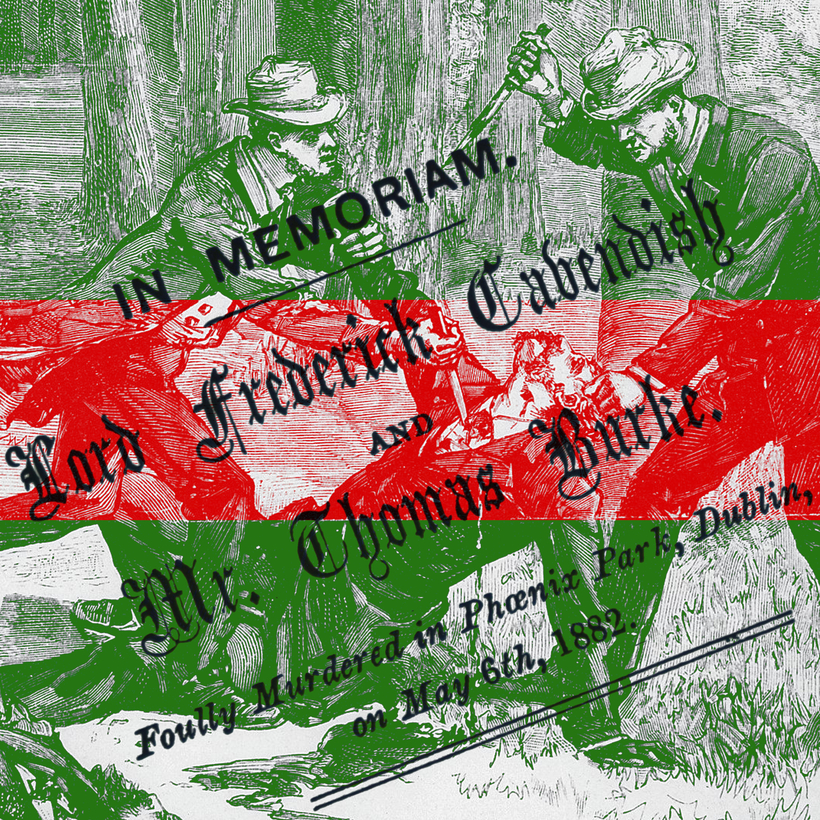

The murders in the Phoenix Park in May 1882 of two of the British administration’s most powerful officials in Ireland has sometimes been treated almost as a footnote to the sweep of events that ultimately led to the settlement of 1921 and the emergence of two new states on this island.

But the assassination of chief secretary Lord Frederick Cavendish and undersecretary Thomas Burke literally changed the course of Irish history, destroying the prospect of an amicable settlement between Ireland and England and fatally undermining the constitutional processes that might have delivered Home Rule before the death of Charles Stewart Parnell in 1891.