Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy in America Who Got Away by Ann Hagedorn

On November 2, 2007, after George W. Bush peered into his eyes and saw his soul but before the rest of the world had gotten a good look, Vladimir Putin posthumously bestowed Russia’s highest award to an American-born scientist and World War II vet named George Koval, who had died the previous year.

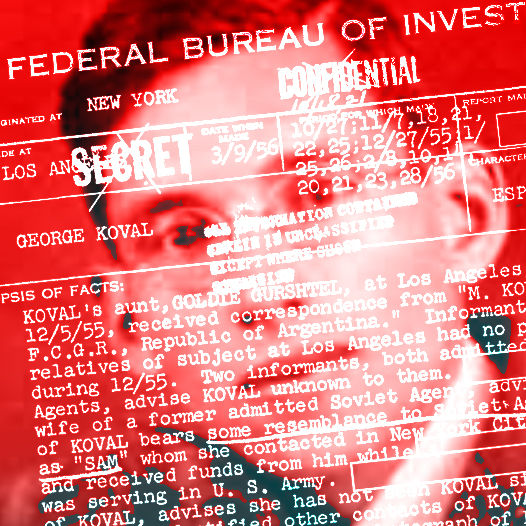

The Kremlin’s announcement made public what the F.B.I. had sought for more than half a century to keep quiet: that Koval was in fact a Soviet spy who had successfully infiltrated the Manhattan Project. The intelligence he gathered was said to have sped the U.S.S.R.’s development of its own atomic bomb.