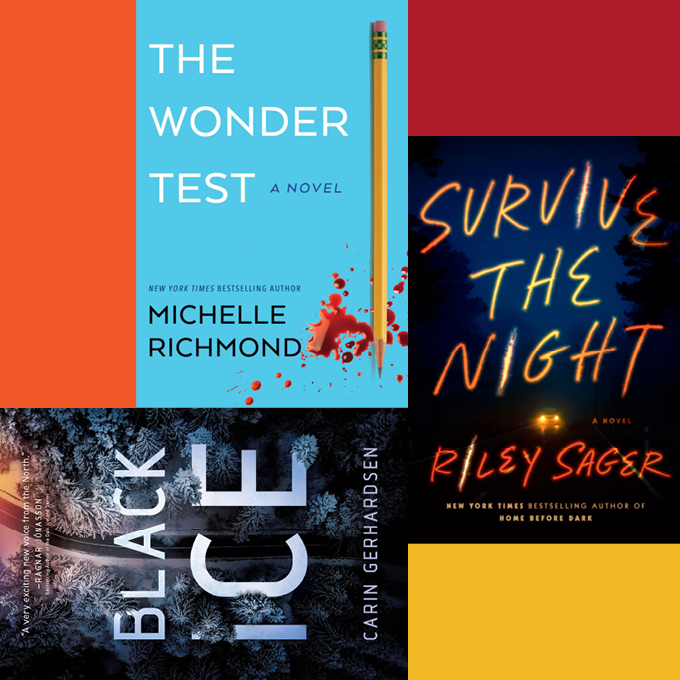

The Wonder Test by Michelle Richmond

Think you test well? Then take a crack at this question: “Is it better to do the right thing for the wrong reason or the wrong thing for the right reason? Using diacritical logic, chart your answer.” I doubt that diacritical logic exists, but using plain vanilla logic, it’s fair to say that in Michelle Richmond’s The Wonder Test, nearly everyone does the wrong thing for the wrong reason.

The S.A.T. pales next to the Wonder Test, a ridiculously impossible standardized exam that’s the No. 1 priority for students at the public high school in Greenfield, in the heart of Silicon Valley. They devote every day to mastering it so that the school can maintain its coveted status as the top scorer in the nation, “status” being the operative word.