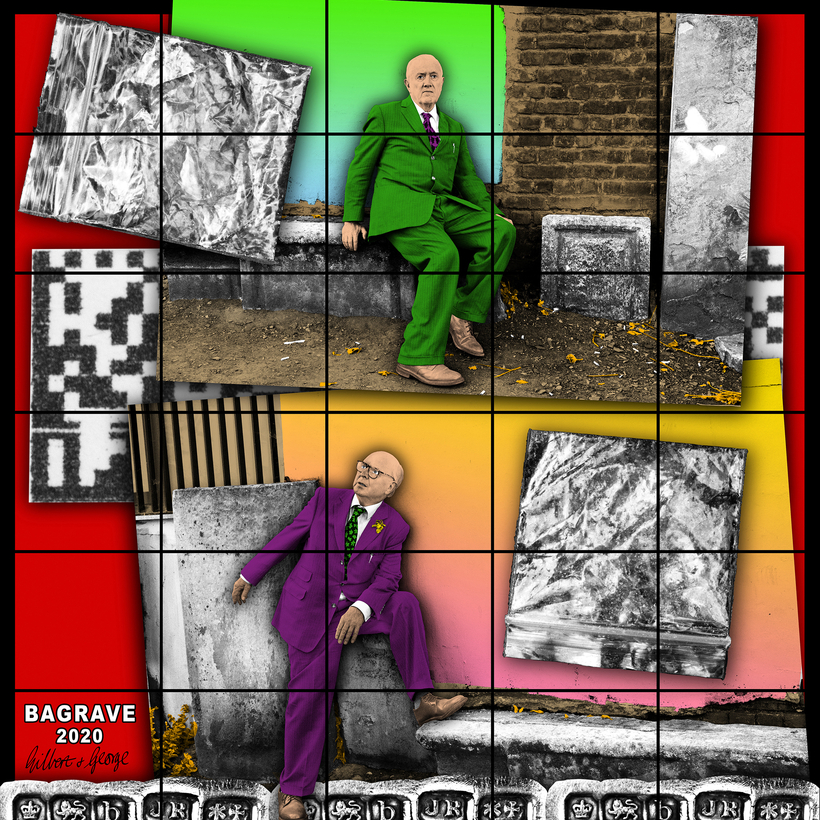

“They present as conservative, but their pictures are fearless and radical,” says Tom Hunt, a director at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in London. He’s talking about that singular artistic marriage of two men—Gilbert Prousch and George Passmore—companions in life and art, who met at Saint Martin’s School of Art and united under the signature Gilbert & George when they began exhibiting as “living sculptures,” in 1968. They never looked back.

Over the last 18 months, the British duo has created approximately 85 New Normal Pictures, a series whose title refers to the pandemic’s life-changing lockdowns. Twenty-six showed at London’s White Cube in April and May; through July 31, Thaddaeus Ropac’s Paris Pantin gallery presents a different 19 from the series.